The year 2017 has only just begun and it is already a turbulent one. The news is full of raucous calls for reinforcement of borders and populist rhetoric asserting nationalism. A wave of world leaders seem to be winning mandates on the platform of nationalism and a reversion to what the world used to be – cleaner, neater, ethically pure and less hospitable to migrants.

Often, this makes those of us who live outside our own homelands question who is ‘Us’ and who exactly are ‘Them’. At a talk recently in Washington D.C., an Indian-American civil servant recalled how she had to testify before the US Congress. As she gave her account of what would work best for US foreign policy for South Asia, one of the Congressmen quizzing her mistook her for an Indian government official, and asked her to relay a message to the Indian government.

The exchange went viral on social media. It set off a debate on what is truly American. As she recounted her story, it was clear that even though she regarded herself as an American - she was born and educated in the US and had dedicated herself to serving her country - she was actually perceived by the Congressman as a brown woman: an Indian, one of ‘them’ rather than ‘us’.

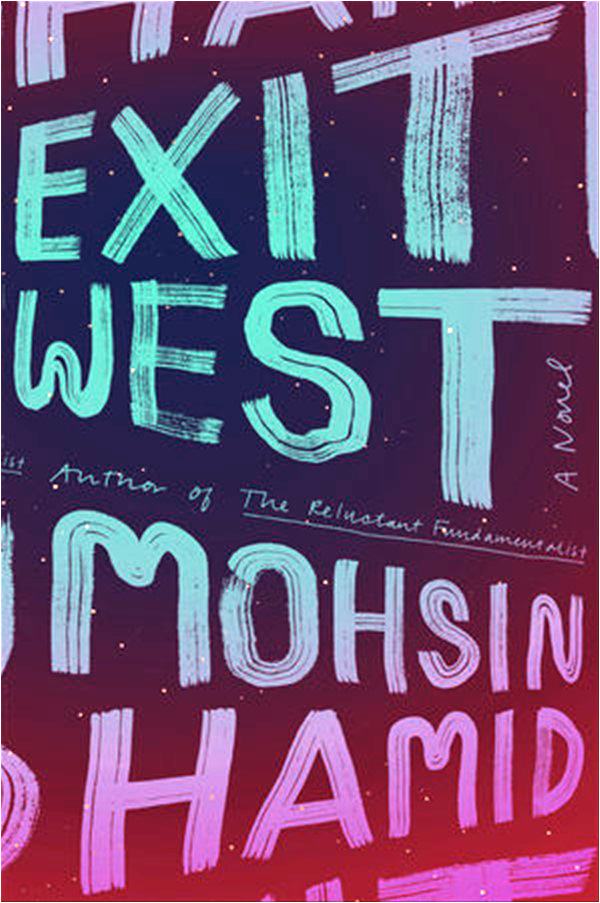

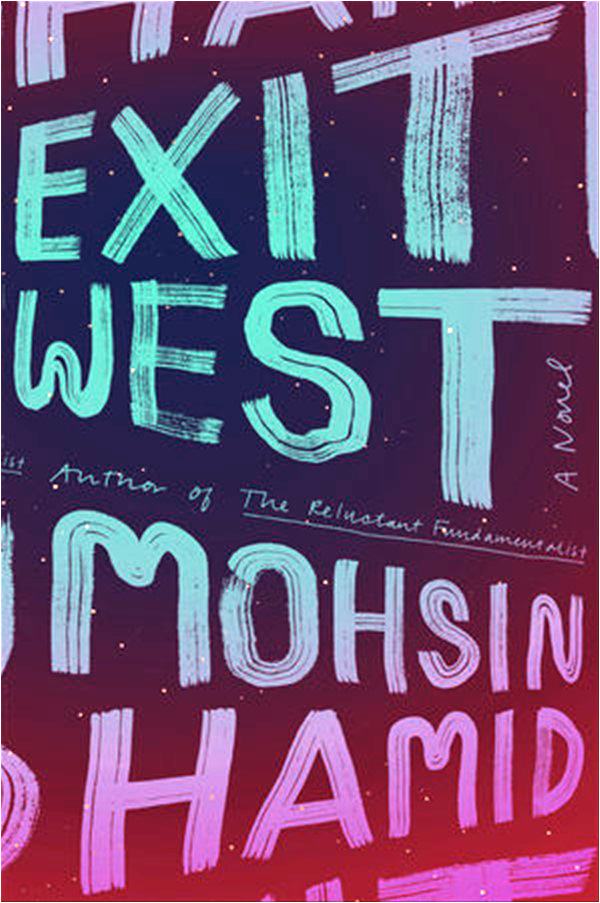

These themes of acquired and natural identity are explored in a nuanced way by Mohsin Hamid in his latest book Exit West. The book was launched recently in Washington D.C. at the book store ‘Politics and Prose’. It was one of many appearances he is making as part of a dizzying 25-city book tour. The book store was crammed with people. Extra lines of chairs had to be added for the overflowing audience. The crowd was mixed: family, friends, South Asian lawyers and tech geeks, Jewish policy makers and all manner of avid readers of Mohsin Hamid’s books.

The fact that Hamid can attract large crowds is no surprise. Over the years, he has shown a consistency in being able to write novels that are a literary touchstone of our time. These works discuss issues of our time and place in it - of reluctant fundamentalism in the post 9/11 period, of what it means to be Filthy Rich in Rising Asia in 2013 and now, topically for 2017, the concept of refugees.

Hamid explained that the term ‘refugee’ is a legal concept. Beyond the traditional notion of seeking refuge, it refers to those 63 million people driven by desperation from their homes and who are accorded international protection and privileges.

The host community protects them as a moral obligation, even though there is no legal need to do so under international treaties. They differ from migrants, who exercise a choice to leave their homeland for better opportunities elsewhere – usually for economic advantage. Unlike refugees, they have the choice to return. Mohsin Hamid’s latest novel explores what it means to be a refugee and what happens to people before and after they become refugees.

According to Salman Rushdie, the essence of a good writer is having a good understanding of oneself. Hamid has clearly done that - exploring through his life and writings the challenge of living within and between worlds. He stands and observes them as a bystander. We all have experienced these feelings of being the outsider, whether within our families, social lives, school or at work. It is in feeling comfortable with these identities and in articulating them that most of us fall short.

Hamid’s two protagonists in Exit West - Nadia and Saeed – venture out on several journeys and identities during their lives. Nadia wears flowing black robes: not because she is pious but because it allows her freedom to do what she wants. Saeed works in advertising: he is almost apologetic about not praying and tries to find common ground with Nadia when seeing her in black robes. As their nameless city disintegrates around them, Nadia and Saeed seek refuge overseas, leaving behind his father, their families and all that is familiar. The book uses the notion of doors - the magic portals that allow for a convenient way to travel across worlds and across time and space into different countries.

Modern technology allows us those portals in real life. I, for example, float within a virtual world - partly fast-forwarding to a conference room in Beijing where I have to travel next week for meetings. While preparing for these meetings, I am listening to a qawali that I last heard on a beautiful spring evening in the walled city of Lahore. I am physically sitting in my home in Washington DC. As I look out of my bedroom window, I can admire cherry blossoms and the falling snowflakes freezing their bloom. For me, as for many relocated expatriates, it is entirely natural to co-exist like this - to mentally tune in and out of several countries and realities at the click of a button.

So what is the impact of Hamid’s words for the modern reader? One consequence seems to be that it is legitimate to be our complicated mongrel selves, to be living simultaneously in several worlds. He reminds us that it is acceptable to be an outsider, even from within - and to connect at a very basic human level, regardless of where one comes from or is going to. The migrants are not the refugees and ‘them’. We are all ‘us’ and we are all ‘them’. We are all migrants in a way on Earth, morphing and growing with different experiences and traversing these virtual borders.

To capture that essence is what Hamid does with elegant prose and thoughtfulness that makes reading his work and listening to him such a worthwhile, stimulating and thought-provoking experience.

The author is based in Washington D.C.

Often, this makes those of us who live outside our own homelands question who is ‘Us’ and who exactly are ‘Them’. At a talk recently in Washington D.C., an Indian-American civil servant recalled how she had to testify before the US Congress. As she gave her account of what would work best for US foreign policy for South Asia, one of the Congressmen quizzing her mistook her for an Indian government official, and asked her to relay a message to the Indian government.

The exchange went viral on social media. It set off a debate on what is truly American. As she recounted her story, it was clear that even though she regarded herself as an American - she was born and educated in the US and had dedicated herself to serving her country - she was actually perceived by the Congressman as a brown woman: an Indian, one of ‘them’ rather than ‘us’.

These themes of acquired and natural identity are explored in a nuanced way by Mohsin Hamid in his latest book Exit West. The book was launched recently in Washington D.C. at the book store ‘Politics and Prose’. It was one of many appearances he is making as part of a dizzying 25-city book tour. The book store was crammed with people. Extra lines of chairs had to be added for the overflowing audience. The crowd was mixed: family, friends, South Asian lawyers and tech geeks, Jewish policy makers and all manner of avid readers of Mohsin Hamid’s books.

The fact that Hamid can attract large crowds is no surprise. Over the years, he has shown a consistency in being able to write novels that are a literary touchstone of our time. These works discuss issues of our time and place in it - of reluctant fundamentalism in the post 9/11 period, of what it means to be Filthy Rich in Rising Asia in 2013 and now, topically for 2017, the concept of refugees.

Hamid explained that the term ‘refugee’ is a legal concept. Beyond the traditional notion of seeking refuge, it refers to those 63 million people driven by desperation from their homes and who are accorded international protection and privileges.

The host community protects them as a moral obligation, even though there is no legal need to do so under international treaties. They differ from migrants, who exercise a choice to leave their homeland for better opportunities elsewhere – usually for economic advantage. Unlike refugees, they have the choice to return. Mohsin Hamid’s latest novel explores what it means to be a refugee and what happens to people before and after they become refugees.

For Hamid, it is legitimate to be our complicated mongrel selves, to be living simultaneously in several worlds

According to Salman Rushdie, the essence of a good writer is having a good understanding of oneself. Hamid has clearly done that - exploring through his life and writings the challenge of living within and between worlds. He stands and observes them as a bystander. We all have experienced these feelings of being the outsider, whether within our families, social lives, school or at work. It is in feeling comfortable with these identities and in articulating them that most of us fall short.

Hamid’s two protagonists in Exit West - Nadia and Saeed – venture out on several journeys and identities during their lives. Nadia wears flowing black robes: not because she is pious but because it allows her freedom to do what she wants. Saeed works in advertising: he is almost apologetic about not praying and tries to find common ground with Nadia when seeing her in black robes. As their nameless city disintegrates around them, Nadia and Saeed seek refuge overseas, leaving behind his father, their families and all that is familiar. The book uses the notion of doors - the magic portals that allow for a convenient way to travel across worlds and across time and space into different countries.

Modern technology allows us those portals in real life. I, for example, float within a virtual world - partly fast-forwarding to a conference room in Beijing where I have to travel next week for meetings. While preparing for these meetings, I am listening to a qawali that I last heard on a beautiful spring evening in the walled city of Lahore. I am physically sitting in my home in Washington DC. As I look out of my bedroom window, I can admire cherry blossoms and the falling snowflakes freezing their bloom. For me, as for many relocated expatriates, it is entirely natural to co-exist like this - to mentally tune in and out of several countries and realities at the click of a button.

So what is the impact of Hamid’s words for the modern reader? One consequence seems to be that it is legitimate to be our complicated mongrel selves, to be living simultaneously in several worlds. He reminds us that it is acceptable to be an outsider, even from within - and to connect at a very basic human level, regardless of where one comes from or is going to. The migrants are not the refugees and ‘them’. We are all ‘us’ and we are all ‘them’. We are all migrants in a way on Earth, morphing and growing with different experiences and traversing these virtual borders.

To capture that essence is what Hamid does with elegant prose and thoughtfulness that makes reading his work and listening to him such a worthwhile, stimulating and thought-provoking experience.

The author is based in Washington D.C.