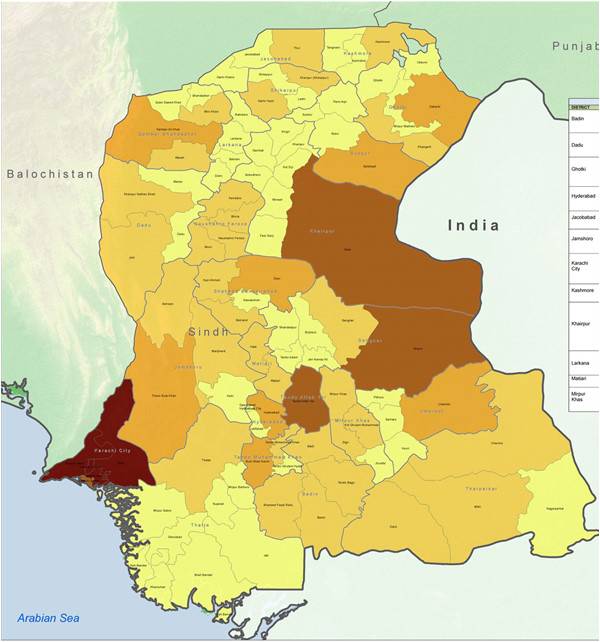

There is nothing quite like a census to shake up a province’s politics. The Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP) is afraid that when the results are out, it will show that there are more people in the urban centres than the rural areas—which have been its stronghold traditionally. But as demographers and urban planners have been warning, this is likely the case today. In fact, by rough estimates Karachi and Hyderabad cities combined probably have more people than the rest of Sindh put together. There has simply been far too much urbanisation and migration to the cities since the last census. And so, if you win the countryside, you might not be guaranteed status of ruling party any more.

In Sindh, the urban-rural divide has persisted since the 1970s. Language-based ethnic conflicts, violence and movements first pitted Mohajirs against Sindhis and later Mohajirs against Pashtuns and Punjabis. The land, the language, the people and their leanings have played out on the political front as party strengths have demonstrated.

The PPP has consolidated its position in rural Sindh since the 1970s but despite this, major landlords and influential tribal chieftains tended to prefer to join anti-PPP forces from 1980 till about 2008. Since then, however, the PPP’s top brass, especially Faryal Talpur, has been hard at work to rope in the big landholding classes.

The people who have joined or said they wanted to join the party include: former PML-N VP Khawaja Muhammad Khan Hoti, former PTI man Nadir Leghari, Irfanullah Marwat, PTI’s Malaika Raza, MQM’s Nabil Gabol, the brother of a Sindhi nationalist, Israr Ghoto, Ghotki’s Sardar Khalid Ahmed Khan Lund, former PML-N MPA Bherulal Balani, former Sindh governor Ishratul Ebad, former federal ministers Faisal Saleh Hayyat and Khalid Ahmed Khan Kharral, PTI leader Zubair Khan, Mirpurkhas district’s Syed Zulfiqar Ali Shah, PML-F’s Imtiaz Shaikh, former PML Punjab MPAs Lubna Tariq and her husband Malik Tariq Muslim, PML-F’s Jam Farooq and Jam Qaim Ali, PTI’s Sardar Jam Karim Jamoot.

Although Sindhi nationalists are a force that cannot be ignored—especially in educational institutions, sections of the intelligentsia and youth—they have been unable to put a dent in the PPP’s electoral foundations. And if things stay as they are, the PPP is likely to win again in the general elections in 2018.

Two main parties active at the national level, the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf and the Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz, have barely registered with voters in Sindh. This left the playing field open to the PPP by default. A number of politicians, who had defeated PPP candidates in the 2013 general polls, were left with no choice but to join the party given that the PML-N completely neglected them. Take the example of State Minister for Communication Abdul Hakeem Baloch. As any child will tell you from Sukkur to Badin, the road to politics and government runs through Bilawal House.

This favourable political landscape has not, however, inoculated the PPP from tough urban challenges. The PPP can only profit from the paramilitary operation against terrorism, crime and corruption if this work is strictly limited to Sindh’s cities. We also need to see if the Mohajir vote is divided among the new factions of the Muttahida Qaumi Movement in the next elections.

Another challenge is the movement of the middle-class and professionals championed by the PTI’s Imran Khan. As compared to the MQM, the PTI, so far, has no consolidated vote pockets in the urban areas of Sindh nor does it have electables faces to bag votes. Recently, many electables from the PTI, such as its former provincial president Nadir Akmal Laghari, joined the PPP.

Using its provincial government to its advantage, the PPP is trying to exploit the situation after the 18th Amendment which transferred more powers down the ladder to the provinces. This is why we are seeing a shift in PPP circles with people being more keen to stand for a provincial assembly constituency.

After the 2013 election, the PPP started doing some soul-searching as the numbers clearly indicated that it had been hemmed in to the rural areas or Sindh’s countryside. Along the way, a nexus between the bureaucracy and party was forged. Therefore, opposition from Sindhi nationalist forces was extinguished. To Sindhi intelligentsia, the PPP is inextricably representing the interest of Sindhis now. And as the census looks like more and more of a threat to the Sindhi cause, the opposition from the PPP finds a more and more welcoming audience.

In many ways, the PPP has established a troika of a coherent electoral system based on party, landlords and government functionaries (the provincial bureaucracy). To many analysts, this is the key to success in rural Sindh.

But there is more at stake for the PPP in the present scenario. In the short term, the results of the ongoing Rangers-led operation in Sindh’s urban centers and demarcations and delimitation on the basis of the new census matter the most for the politics of Sindh. This is why all key political players from the PPP, the MQM and the PTI, have been monitoring the process with a hawkish gaze.

The PPP is confident, however, that the Rangers-led anti-crime operation and weak social basis of the PTI, especially in rural Sindh, will change its fortunes. Whether the PPP will co-exist with or fight the Mohajir parties will depend on what unfolds. The Establishment still thinks that the MQM (London) has suffered but not as badly as it feared. The party still has the potential to destabilize the situation as it did in past, and can do something quite rapidly to produce unforeseen and wanted results. It can dramatically support a rival group, even on Election Day, to turn the table on its opponents.

They know that the rapid urbanization and migration has altered Sindh’s urban-rural population balance. This will reshape the dynamics of politics in the province. Recent events have proven that these challenges go beyond simple headcounts necessary for state and capitalist development. This is why the Sindhi- and Urdu-speaking politicians find themselves under overwhelming pressure from the middle class intelligentsia from their communities to raise voices for their rights and share in representation and governance.

Generally speaking, Sindhis and Mohajirs share common concerns over the presence of Afghan refugee, Pashtun and Punjabi economic migrants in Sindh. Add to this the sprawling diversity of urban centers with all its attendant effects on resource management and politics. Both the PPP and the MQM fear that urban-based movements are most likely to upset the apple cart.

The crackdown on Pashtuns, accusing them as hiding identities as Afghan refugees, in rural Sindh has not sit well with the urban Pashtun classes of the province. Despite this, sections of the Pashtun middle classes living in Sindh’s countryside consider the PPP their best choice as a buffer. And, given that the Awami National Party (ANP) was decimated by the Taliban in Karachi, it will not have a hard time aligning itself with the PPP in the countryside. But urban Pashtun are more inclined to lean to other parties, such as the PTI and PML-N and some would even advocate an alliance with the MQM (Pakistan). We are also seeing the emergence of new feelings of shared culture and politics among the urban sections of Mohajirs, Pashtuns, Punjabis, Hazaraywals (Hindko speakers), and Seraiki-speaking people. The one plausible consequence of all this could be a strong support base for new political forces that could rise to challenge the hegemony of the PPP and MQM. If the PTI and PML-N want to cash in, though, they will have to get their house in order.

The writer is a Karachi-based independent researcher

In Sindh, the urban-rural divide has persisted since the 1970s. Language-based ethnic conflicts, violence and movements first pitted Mohajirs against Sindhis and later Mohajirs against Pashtuns and Punjabis. The land, the language, the people and their leanings have played out on the political front as party strengths have demonstrated.

The PPP has consolidated its position in rural Sindh since the 1970s but despite this, major landlords and influential tribal chieftains tended to prefer to join anti-PPP forces from 1980 till about 2008. Since then, however, the PPP’s top brass, especially Faryal Talpur, has been hard at work to rope in the big landholding classes.

After the 2013 elections, the PPP did some soul searching and realised it had been restricted to Sindh's countryside. It developed the winning troika of the babu, jiyala and sardar. And with devolution giving more power to the provinces, more aspirants are attracted to MPA or provincial seats

The people who have joined or said they wanted to join the party include: former PML-N VP Khawaja Muhammad Khan Hoti, former PTI man Nadir Leghari, Irfanullah Marwat, PTI’s Malaika Raza, MQM’s Nabil Gabol, the brother of a Sindhi nationalist, Israr Ghoto, Ghotki’s Sardar Khalid Ahmed Khan Lund, former PML-N MPA Bherulal Balani, former Sindh governor Ishratul Ebad, former federal ministers Faisal Saleh Hayyat and Khalid Ahmed Khan Kharral, PTI leader Zubair Khan, Mirpurkhas district’s Syed Zulfiqar Ali Shah, PML-F’s Imtiaz Shaikh, former PML Punjab MPAs Lubna Tariq and her husband Malik Tariq Muslim, PML-F’s Jam Farooq and Jam Qaim Ali, PTI’s Sardar Jam Karim Jamoot.

Although Sindhi nationalists are a force that cannot be ignored—especially in educational institutions, sections of the intelligentsia and youth—they have been unable to put a dent in the PPP’s electoral foundations. And if things stay as they are, the PPP is likely to win again in the general elections in 2018.

Two main parties active at the national level, the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf and the Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz, have barely registered with voters in Sindh. This left the playing field open to the PPP by default. A number of politicians, who had defeated PPP candidates in the 2013 general polls, were left with no choice but to join the party given that the PML-N completely neglected them. Take the example of State Minister for Communication Abdul Hakeem Baloch. As any child will tell you from Sukkur to Badin, the road to politics and government runs through Bilawal House.

This favourable political landscape has not, however, inoculated the PPP from tough urban challenges. The PPP can only profit from the paramilitary operation against terrorism, crime and corruption if this work is strictly limited to Sindh’s cities. We also need to see if the Mohajir vote is divided among the new factions of the Muttahida Qaumi Movement in the next elections.

Another challenge is the movement of the middle-class and professionals championed by the PTI’s Imran Khan. As compared to the MQM, the PTI, so far, has no consolidated vote pockets in the urban areas of Sindh nor does it have electables faces to bag votes. Recently, many electables from the PTI, such as its former provincial president Nadir Akmal Laghari, joined the PPP.

Using its provincial government to its advantage, the PPP is trying to exploit the situation after the 18th Amendment which transferred more powers down the ladder to the provinces. This is why we are seeing a shift in PPP circles with people being more keen to stand for a provincial assembly constituency.

After the 2013 election, the PPP started doing some soul-searching as the numbers clearly indicated that it had been hemmed in to the rural areas or Sindh’s countryside. Along the way, a nexus between the bureaucracy and party was forged. Therefore, opposition from Sindhi nationalist forces was extinguished. To Sindhi intelligentsia, the PPP is inextricably representing the interest of Sindhis now. And as the census looks like more and more of a threat to the Sindhi cause, the opposition from the PPP finds a more and more welcoming audience.

In many ways, the PPP has established a troika of a coherent electoral system based on party, landlords and government functionaries (the provincial bureaucracy). To many analysts, this is the key to success in rural Sindh.

But there is more at stake for the PPP in the present scenario. In the short term, the results of the ongoing Rangers-led operation in Sindh’s urban centers and demarcations and delimitation on the basis of the new census matter the most for the politics of Sindh. This is why all key political players from the PPP, the MQM and the PTI, have been monitoring the process with a hawkish gaze.

The PPP is confident, however, that the Rangers-led anti-crime operation and weak social basis of the PTI, especially in rural Sindh, will change its fortunes. Whether the PPP will co-exist with or fight the Mohajir parties will depend on what unfolds. The Establishment still thinks that the MQM (London) has suffered but not as badly as it feared. The party still has the potential to destabilize the situation as it did in past, and can do something quite rapidly to produce unforeseen and wanted results. It can dramatically support a rival group, even on Election Day, to turn the table on its opponents.

They know that the rapid urbanization and migration has altered Sindh’s urban-rural population balance. This will reshape the dynamics of politics in the province. Recent events have proven that these challenges go beyond simple headcounts necessary for state and capitalist development. This is why the Sindhi- and Urdu-speaking politicians find themselves under overwhelming pressure from the middle class intelligentsia from their communities to raise voices for their rights and share in representation and governance.

Generally speaking, Sindhis and Mohajirs share common concerns over the presence of Afghan refugee, Pashtun and Punjabi economic migrants in Sindh. Add to this the sprawling diversity of urban centers with all its attendant effects on resource management and politics. Both the PPP and the MQM fear that urban-based movements are most likely to upset the apple cart.

The crackdown on Pashtuns, accusing them as hiding identities as Afghan refugees, in rural Sindh has not sit well with the urban Pashtun classes of the province. Despite this, sections of the Pashtun middle classes living in Sindh’s countryside consider the PPP their best choice as a buffer. And, given that the Awami National Party (ANP) was decimated by the Taliban in Karachi, it will not have a hard time aligning itself with the PPP in the countryside. But urban Pashtun are more inclined to lean to other parties, such as the PTI and PML-N and some would even advocate an alliance with the MQM (Pakistan). We are also seeing the emergence of new feelings of shared culture and politics among the urban sections of Mohajirs, Pashtuns, Punjabis, Hazaraywals (Hindko speakers), and Seraiki-speaking people. The one plausible consequence of all this could be a strong support base for new political forces that could rise to challenge the hegemony of the PPP and MQM. If the PTI and PML-N want to cash in, though, they will have to get their house in order.

The writer is a Karachi-based independent researcher