Pakistan’s economy is growing because people are moving. The World Economic Forum acknowledges this in its definition of mobility: “the movement of people and goods ... a fundamental human need and a key enabler of economic and social prosperity”.

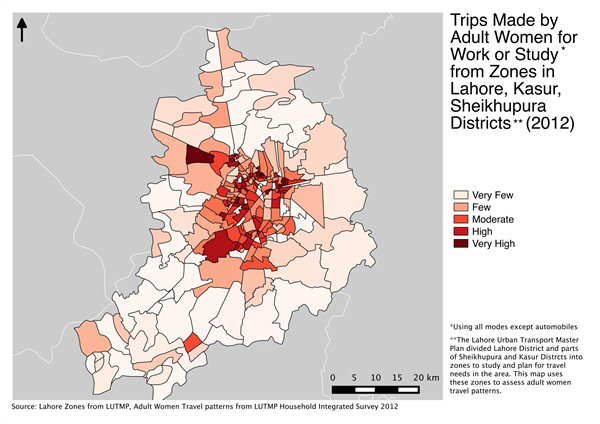

But women in Pakistan are noticeably less mobile than men. As revealed by an ongoing study on women’s mobility in Lahore from the Center for Economic Research in Pakistan (CERP) and Duke University, this is because their transport choices are limited. Women rely more on public transport because options for private transport, such as motorbikes, are taboo for women. The study found that women in Lahore are 30 percent more likely than men to use public transport services such as public wagons and buses. Women are also 150 percent more likely to use alternative forms of informal “public” transport such as rickshaws and qingqis. Yet social norms and fear of harassment when coming into close contact with unrelated men discourage women from using public transport as well.

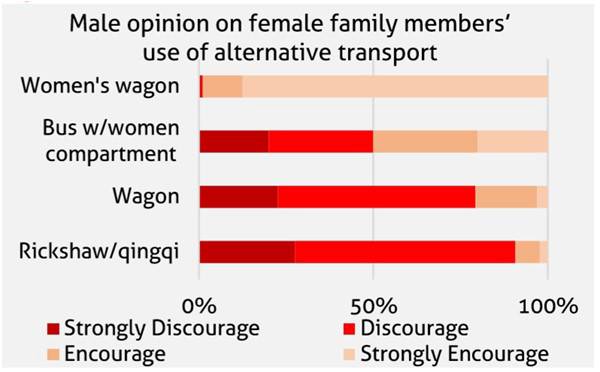

According to the CERP-Duke study, 70 percent of men surveyed in 1,000 households discourage women from taking public wagon services and about 90 percent discourage them from taking rickshaws and qingqis (see table).

Getting to and waiting at stops can also be a stressful experience for women. A pilot survey in Lahore, of which 80 percent of respondents were female, found that nearly 30 percent of surveyed households think it is unsafe for women to walk in their own neighborhood. Women in focus groups reported that men stare at them, make comments, follow them to their destination or physically touch them while passing by.

“I felt very scared walking alone to bus stops so I made sure my younger brother accompanied me wherever I went,” said a female focus group participant.

This ultimately makes it harder for women to access jobs or pursue activities of their interest outside the home—reducing their ability to participate in public life.

The government has taken steps to address this problem by creating separate compartments for women. It has also created a Pink Bus service exclusive to women on three routes; the vast majority of males are comfortable with their female family members traveling on such a women’s only service, even those who discourage their female family members from traveling on other modes.

The government has also initiated the Women on Wheels project to increase women’s use of motorcycles. Civil society initiatives such as the Pink Rickshaw and Girls at Dhabas have also called attention to the need for normalizing women’s presence in public.

But much more can be done to have a wider impact. Existing women-only services reach a very limited number of areas. One in five households in Lahore reports their neighborhood does not even have access to a bus with a women’s-only compartment, let alone a women’s-only vehicle.

The CERP study lays out the following actions the government can take to increase women’s mobility.

Continue the expansion of public transport networks: More public transport routes should focus on providing vehicles with less crowding and separate sections for women.

If women’s-only services are used, get more value for money by improving design: The existing large women’s-only pink buses typically run half empty, making them less cost efficient. These services can achieve better value for money by using small vehicles that fill up quickly, and running on routes where there is crowding on vehicles and there are not already buses with separate sections for women.

Maintain a fixed, consistent schedule for all public transport services: Not only would this improve service for all passengers, but keeping a reliable schedule with predictable timings would reduce wait times on the street, where women are highly vulnerable to harassment. Pilot services CERP conducted with the collaboration of the Lahore Transport Company showed that this is possible even in uncertain traffic conditions.

Work with informal operators to improve public transport coverage in the city’s outskirts : City outskirts, where public transport coverage is limited, are served by informal operators. The government should engage with these operators to provide a reliable transport service in these areas on a publicized timetable.

Train public transport staff (especially drivers and conductors) on sexual harassment: Public transport staff currently receive no sexual harassment training. They should be instructed on the standards of conduct expected of them, as well as how to deal with cases of harassment committed by passengers. A pilot training CERP conducted with the Aurat Foundation and Women in Struggle for Empowerment (WISE) was highly successful, and there is interest from the Aurat Foundation to conduct larger-scale trainings with the government. Critically, government and vehicle operators must not just train but also monitor staff on an ongoing basis and hold them accountable for meeting these expectations.

Use evidence to design, monitor and evaluate transport policies and initiatives: There is a dearth of rigorous assessment to inform new policies that better serve women’s demands for public transport. Decisions are often made ad-hoc based on the judgements of particular decision makers, not on solid data. Regular data collection and analysis—such as through surveys of female riders that can be conducted at negligible cost—would help the government craft smarter policies that increase women’s mobility in public.

Recent efforts to improve women’s access to public transport such as the Pink Bus and Women on Wheels need to be better monitored and evaluated to determine their impact. With this information, the government would be in a stronger position to scale them up to benefit more women.

Public transport alone is not enough: Women need to both feel and actually be safe when walking to and waiting at stops. Building sidewalks, providing street lighting and improving police attention to stops and street safety are vital for bringing more women out into public.

Not only could these actions be a practical solution for women who want to use public transport, but they can help create a culture where women feel secure and empowered to exercise their freedom of movement.

This is a summary of the policy brief “Overcoming barriers to women’s mobility,” by Fizzah Sajjad, Kate Vyborny, Ghulam Abbas Anjum and Erica Field is based on the first stage of the CERP-Duke Women’s Mobility project. The full brief is available on the Consortium for Development Policy Research’s website

But women in Pakistan are noticeably less mobile than men. As revealed by an ongoing study on women’s mobility in Lahore from the Center for Economic Research in Pakistan (CERP) and Duke University, this is because their transport choices are limited. Women rely more on public transport because options for private transport, such as motorbikes, are taboo for women. The study found that women in Lahore are 30 percent more likely than men to use public transport services such as public wagons and buses. Women are also 150 percent more likely to use alternative forms of informal “public” transport such as rickshaws and qingqis. Yet social norms and fear of harassment when coming into close contact with unrelated men discourage women from using public transport as well.

According to the CERP-Duke study, 70 percent of men surveyed in 1,000 households discourage women from taking public wagon services and about 90 percent discourage them from taking rickshaws and qingqis

According to the CERP-Duke study, 70 percent of men surveyed in 1,000 households discourage women from taking public wagon services and about 90 percent discourage them from taking rickshaws and qingqis (see table).

Getting to and waiting at stops can also be a stressful experience for women. A pilot survey in Lahore, of which 80 percent of respondents were female, found that nearly 30 percent of surveyed households think it is unsafe for women to walk in their own neighborhood. Women in focus groups reported that men stare at them, make comments, follow them to their destination or physically touch them while passing by.

“I felt very scared walking alone to bus stops so I made sure my younger brother accompanied me wherever I went,” said a female focus group participant.

This ultimately makes it harder for women to access jobs or pursue activities of their interest outside the home—reducing their ability to participate in public life.

The government has also initiated the Women on Wheels project to increase women's use of motorcycles. Civil society initiatives such as the Pink Rickshaw and Girls at Dhabas have also called attention to the need for normalizing women's presence in public

The government has taken steps to address this problem by creating separate compartments for women. It has also created a Pink Bus service exclusive to women on three routes; the vast majority of males are comfortable with their female family members traveling on such a women’s only service, even those who discourage their female family members from traveling on other modes.

The government has also initiated the Women on Wheels project to increase women’s use of motorcycles. Civil society initiatives such as the Pink Rickshaw and Girls at Dhabas have also called attention to the need for normalizing women’s presence in public.

But much more can be done to have a wider impact. Existing women-only services reach a very limited number of areas. One in five households in Lahore reports their neighborhood does not even have access to a bus with a women’s-only compartment, let alone a women’s-only vehicle.

The CERP study lays out the following actions the government can take to increase women’s mobility.

Continue the expansion of public transport networks: More public transport routes should focus on providing vehicles with less crowding and separate sections for women.

If women’s-only services are used, get more value for money by improving design: The existing large women’s-only pink buses typically run half empty, making them less cost efficient. These services can achieve better value for money by using small vehicles that fill up quickly, and running on routes where there is crowding on vehicles and there are not already buses with separate sections for women.

Maintain a fixed, consistent schedule for all public transport services: Not only would this improve service for all passengers, but keeping a reliable schedule with predictable timings would reduce wait times on the street, where women are highly vulnerable to harassment. Pilot services CERP conducted with the collaboration of the Lahore Transport Company showed that this is possible even in uncertain traffic conditions.

Work with informal operators to improve public transport coverage in the city’s outskirts : City outskirts, where public transport coverage is limited, are served by informal operators. The government should engage with these operators to provide a reliable transport service in these areas on a publicized timetable.

Train public transport staff (especially drivers and conductors) on sexual harassment: Public transport staff currently receive no sexual harassment training. They should be instructed on the standards of conduct expected of them, as well as how to deal with cases of harassment committed by passengers. A pilot training CERP conducted with the Aurat Foundation and Women in Struggle for Empowerment (WISE) was highly successful, and there is interest from the Aurat Foundation to conduct larger-scale trainings with the government. Critically, government and vehicle operators must not just train but also monitor staff on an ongoing basis and hold them accountable for meeting these expectations.

Use evidence to design, monitor and evaluate transport policies and initiatives: There is a dearth of rigorous assessment to inform new policies that better serve women’s demands for public transport. Decisions are often made ad-hoc based on the judgements of particular decision makers, not on solid data. Regular data collection and analysis—such as through surveys of female riders that can be conducted at negligible cost—would help the government craft smarter policies that increase women’s mobility in public.

Recent efforts to improve women’s access to public transport such as the Pink Bus and Women on Wheels need to be better monitored and evaluated to determine their impact. With this information, the government would be in a stronger position to scale them up to benefit more women.

Public transport alone is not enough: Women need to both feel and actually be safe when walking to and waiting at stops. Building sidewalks, providing street lighting and improving police attention to stops and street safety are vital for bringing more women out into public.

Not only could these actions be a practical solution for women who want to use public transport, but they can help create a culture where women feel secure and empowered to exercise their freedom of movement.

This is a summary of the policy brief “Overcoming barriers to women’s mobility,” by Fizzah Sajjad, Kate Vyborny, Ghulam Abbas Anjum and Erica Field is based on the first stage of the CERP-Duke Women’s Mobility project. The full brief is available on the Consortium for Development Policy Research’s website