The year was 1979. His Imperial Majesty, the Shahanshah, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi of Iran, was homeless and gravely ill. The once-powerful monarch who had ruled a modern prosperous country for 37 years from the majestic Peacock Throne, commanded a powerful army and controlled massive oil wealth, had been driven out of Iran by the followers of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. He was now desperately seeking refuge, wandering from country to country, while battling a terminal illness, Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma, a form of cancer of the immune system.

The year was 1979. His Imperial Majesty, the Shahanshah, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi of Iran, was homeless and gravely ill. The once-powerful monarch who had ruled a modern prosperous country for 37 years from the majestic Peacock Throne, commanded a powerful army and controlled massive oil wealth, had been driven out of Iran by the followers of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. He was now desperately seeking refuge, wandering from country to country, while battling a terminal illness, Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma, a form of cancer of the immune system.Many in Pakistan had closely followed the ebb and flow of the Shah’s fortune. At the peak of his power, he had fostered a close relationship with Pakistan. Iran was the first country that recognised Pakistan after independence and the Shah was the first head of state to pay a state visit in March 1950. In his book Fauji Raj ke Pahle Das Sal, the late Mr. Altaf Gohur narrated a conversation that President Ayub Khan had with the Shah in July 1958 during the Bagdad Pact meeting in Ankara. The Shah was contemplating a confederation of Iran and Pakistan, which would control defense, treasury and foreign affairs, but otherwise the two countries would have separate governments. His idea was to have a single defense force, supported by Iran’s anticipated vast oil wealth. The proposal made no headway, however, and was relegated to the dustbin of history.

Yet, the Shah remained concerned about Pakistan’s security and integrity. In his book, Iran and Pakistan, Alex Vatanka, a senior fellow at the Middle East Institute, Washington, recounted that the Shah, during his meeting with Dr. Henry Kissinger in July 1973, stated that he had warned the Indians: “An attack on Pakistan would involve Iran, and Iran could not tolerate further disintegration of Pakistan.” In his memoir, Answer to History, dictated from his deathbed, the Shah wrote, “I hoped to arrange a meeting between Yahya Khan and the president of the USSR, Podgorny, and thus help avert the conflict between India and Pakistan.” Clearly, his efforts failed.

Nearly four decades have elapsed since the Shah was driven out of Iran on January 16, 1979, a country he never ceased to love. Meanwhile, numerous books have been written about the Islamic revolution and the Shah’s ouster. A narrative has gained currency, especially in the West, that he was a corrupt, tyrannical dictator and an American stooge. Lately, however, some have argued that perhaps the Shah and his rule were not quite the epitome of evil - as has been skillfully portrayed by his adversaries.

Paradoxically, the crimes attributed to the Shah are overshadowed by the well-documented brutalities committed by the revolutionary regime

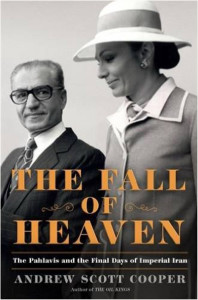

In a new book, The Fall of Heaven, Andrew Scott Cooper, an expert on US-Iran relations at Columbia University, has revisited the Shah’s rule, his legacy and the reasons for his downfall. The author interviewed many people who in some way were related to the revolution. The book traces the progression of the Shah’s rule from his accession to his exile and uncovers some startling findings, never known or made public before.

The Shah has been accused of mass murder and squirreling away at least 25 or even 59 billion dollars to Swiss banks, charges that have never been substantiated. It turned out that his entire assets amounted to less than $100 million. The author cites credible research by Emad al Din Baghi, the Iranian human rights activist and journalist, that shows, contrary to assertions by the Islamic Republic’s partisans that the Shah’s regime had killed thousands of dissidents, he could only confirm 383 fatalities from 1978-1979, the period of the revolution. Of this number, 197 were determined to be guerrilla fighters. The estimated number of political prisoners taken during the Shah’s reign turned out to be only 3,200, not 100,000 as propagated by the regime. For his research, refuting many accusations against the Shah, Emad al Din Baghi was imprisoned by the Iranian Government.

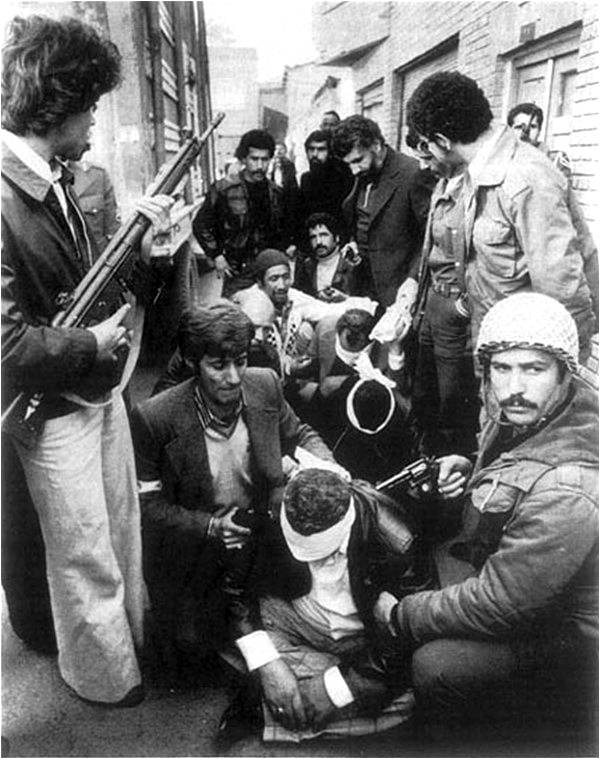

Paradoxically, the crimes attributed to the Shah are overshadowed by the well-documented brutalities committed by the revolutionary regime. Ali Massoud Ansari, Professor in Modern History at St. Andrews University in Scotland, claims that during 1979-1989, when Imam Khomeini was in power, an estimated 12,000 people were executed on charges of being monarchist, gay, leftist or progressive women. There is no way to establish the validity of these statistics. It is, however, well documented that in the earlier days of the revolution several prominent Iranians who had helped Khomeini to power were executed or forced into exile. Abolhassan Banisadr, the first president of the Islamic Republic and Shapour Bakhtiar, the last prime minister of pre-revolution Iran, fearing for their lives, escaped to France. Sadeg Ghotzbadegh, the first foreign minister, accused of plotting a coup, was executed in 1982.

Andrew Cooper’s book raises some intriguing questions, but offers no definitive answers, only speculation. Why did the Shah let the rebellion grow when in the early days, it would have been relatively easy to smother it? His chiefs of the armed forces repeatedly, but unsuccessfully, pleaded with him for permission to use force to control the situation. The book cites Pariz Sabeti, the chief of the intelligence agency Savak, who “had drawn up a contingency plan for the Shah to move to a naval base and allow the security force to smash revolutionary cells, and break the cycle of unrest.” The Shah did not agree for fear of bloodshed. His willpower, energy and ability to take decisive action, it is speculated, had been sapped by his advancing illness. The revolution, meanwhile, mushroomed: culminating in his ouster and exile.

The Fall of Heaven ends with the Shah tearfully leaving the country, ostensibly for a vacation. It does not cover the period of abject desperation that befell him and his family in exile. In her autobiography, An Enduring Love, former queen, Farah (Deba) Pahlavi, narrated the predicament they faced after they left Iran. Initially, they were warmly welcomed with full honors by President Sadat of Egypt, and later by King Hasan II of Morocco. Yet, it was clear that their hospitality was temporary and the royal family was expected to move on. There were strident demands from the new regime in Iran for the Shah’s extradition as the regime wanted to put him on trial and execute him. Any country which offered shelter risked loss of trade and disruption of oil supplies.

Countries and individuals that eagerly sought the Shah’s pleasure in happier times now did not want anything to do with him. France declined to offer him asylum for it could not guarantee his safety. Switzerland and the principality of Monaco had the same excuse. Initially, Margaret Thatcher of Britain was willing to accept him, but later the offer was withdrawn.

The US Government was no more welcoming. Barely a year before, President Jimmy Carter had been lavishly entertained by the Shah at the Niavaran Palace on New Year’s Eve in 1978. Now, the imperial family was homeless and the Shah, in urgent need of medical treatment for cancer, was supplicating for a visa. President Carter, on the intervention of Dr. Henry Kissinger, one of the few remaining loyal friends of the Shah, finally and reluctantly relented. The Shah was admitted for surgery to a New York hospital. The news infuriated the militants in Tehran, and the staff of the American embassy was taken hostage in retaliation. Fifty-Two American embassy personnel were held in captivity for 444 days.

With the Shah engaged in a life-and-death struggle with cancer, the US Government wanted him to leave the country. Former queen Farah Pahlavi in desperation contacted Jehan Sadat, wife of the President of Egypt for help. In the face of dire threats from Iran and opposition from domestic extremists, President Sadat bravely extended an invitation to them to come to Egypt. He personally welcomed the bedraggled royal family at the airport and lodged them at the stately Koubbeh Palace.

The Shah died in a military hospital outside Cairo on July 28, 1980. He was given a state funeral, but only President Nixon and the former King Constantine of Greece were invited to attend. Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi was buried with full honors in Al-Rifai mosque, Cairo, where Egypt’s two former kings, Fuad I and Farouk, are also buried. The Shah was only sixty years old.