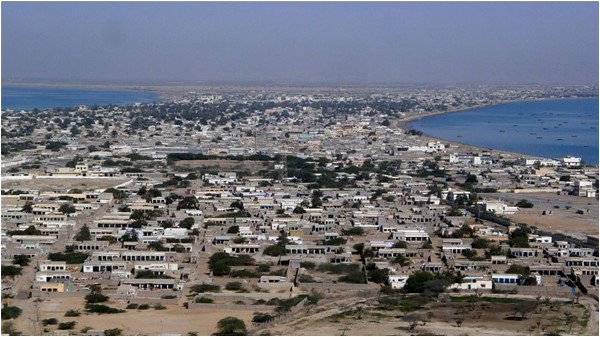

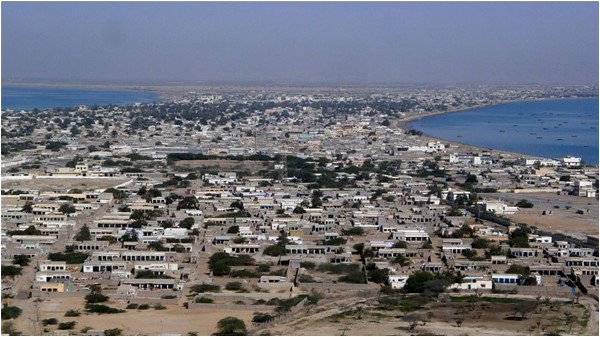

Tweeting up a storm on Tuesday was Andrew Small, the author of The China-Pakistan Axis: Asia’s New Geopolitics. “Chinese ambo in Gwadar: CPEC has now ‘entered into full implementation’; leaders established blueprint, now it’s ‘action, action, action’.” He was referring to an international maritime conference being attended by Pakistan Navy, Iranian officials, Chinese and port officials in Gwadar, which is the linchpin of CPEC, the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor. According to Small, Chinese grants will be paying for a hospital, a vocational training centre, and the area will get a new airport. Chinese companies are providing opportunities for Pakistanis to train with them. But is Pakistan ready for all this action, action, action?

Not long ago, a balance of payments crisis lurked around the corner for its then 250-billion-dollar economy, before the IMF offered a bailout package. This $6.6 billion dragged Pakistan out of a deep trench it had dug itself into after years of ill-conceived decisions and poor planning, bringing about some sort of stability to an otherwise troubled economy.

Things then started to change. Spurred by the first successful democratic transition and then a government that rode on the back of its promise to end load-shedding and terrorism, Pakistan started to gave hints of being stable. Barely a year after Pakistan secured the IMF bailout, neighbouring China sensed the opportunity.

China’s model of investing abroad soon featured Pakistan on its growth map. As we have an estimated population of over 200 million people, high consumption patterns and a relatively safer environment, this meant that China’s plans to tap Europe, the Middle East and Central Asian markets needed to include Pakistan. And we willingly obliged. Pakistan agreed to become part of the One-Belt-One-Road (OBOR) initiative, forming the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor that includes a slew of energy projects as well as investments in roads and railways.

But there is much more to this picture. China, for one, is known to make a deal when it sees one. So does it really come as a surprise that a country into which China is pumping in close to $50 billion in soft loans and investments actually has more to offer than just its location for a corridor?

CPEC has been loudly touted as a game-changer—but little else has been divulged beyond this. The Pakistanis are as inarticulate in their descriptions of it as discreet as the Chinese have been. But one thing is for certain; we will hear and see a lot of China in Pakistan than we have ever before. Their products have flooded markets in every country and their investments have only increased over time.

Pakistan isn’t the only country China has its eyes on. This year Chinese firms have already announced double the record $106 billion in foreign acquisitions they made in 2015, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. Of this, K-Electric’s transaction will be less than 1% of the overall plans to invest abroad. Lately, reports have circulated that the Chinese are interested in buying 40% of the Pakistan Stock Exchange. This comes after a Chinese company already expressed interest in buying a stake in a Pakistani cement company. So why is it that Pakistanis are still so wary of foreign investment? Is it simply because too much of it, according to our standards, is coming from one place? Or is it because we are more comfortable with American or western interest?

A recent conversation I had with an economist of a global bank swayed this way. He made a valid point; Chinese companies don’t interfere in politics, much less like the westerners do. An investment made by the US or European companies comes attached with conditions to protect human or labour rights. In this case, there will be a lot less conditionality involved. This loosely translates into saying that Pakistan can continue to function the way it does, without worrying too much about pleasing the investors. Does this make one feel better? Yes, and no.

The bigger worry is competitiveness. In the FTA signed with China, there are no prizes for guessing who came out on top in the negotiations. China got away with a lot more concessions simply because they had a lot more to offer. In the case of CPEC, Pakistan has been granting Chinese companies tax exemptions as well. In return, we are getting billions of dollars that, otherwise, would have gone elsewhere.

The bigger concern is when Chinese companies go about setting up a business, they make it really hard for inefficient entities to sustain themselves. However, for this to happen, China will have to establish itself in Pakistan a lot more than it currently has. K-Electric has no competitor and its acquisition can only mean greater efficiency given that its acquirer is an expert in the field. On the other hand, the cement industry is close to capacity utilisation and needs expansion anyway.

So for those with concerns that China will somehow control Pakistan with its finger on the button, remember that its model is to invest in countries where there is growth potential. Its own economy is headed for a slowdown and it needs its companies to find investment opportunities elsewhere. Given what we have heard about China, the situation within the country has a lot of room for improvement. Wages are low, but the Chinese government wants to increase consumption. That can’t happen unless China finds other avenues. If it does drive an entity out of business, remember that the company itself needed to be shoved out because it was uncompetitive and unsustainable. All it needed was a little push.

What Pakistan needs to concern itself with is its ability, or lack of, to evolve. Some say that CPEC is another East India Company in the making. Perhaps they are right. But the British were only able to control what was ours since we failed to transform and evolve. We wanted to continue coasting through life without raising our standards and working harder. I am not arguing that we should all necessarily start learning Mandarin, but am proposing that increasing the level of education among people and investing in quality institutions where unbiased knowledge is imparted could be a start.

If the Chinese are able to drive any of us out of business, it would be our fault?simply because we weren’t good enough.

Samir Ahmad is a business writer based in Karachi

Not long ago, a balance of payments crisis lurked around the corner for its then 250-billion-dollar economy, before the IMF offered a bailout package. This $6.6 billion dragged Pakistan out of a deep trench it had dug itself into after years of ill-conceived decisions and poor planning, bringing about some sort of stability to an otherwise troubled economy.

Things then started to change. Spurred by the first successful democratic transition and then a government that rode on the back of its promise to end load-shedding and terrorism, Pakistan started to gave hints of being stable. Barely a year after Pakistan secured the IMF bailout, neighbouring China sensed the opportunity.

China’s model of investing abroad soon featured Pakistan on its growth map. As we have an estimated population of over 200 million people, high consumption patterns and a relatively safer environment, this meant that China’s plans to tap Europe, the Middle East and Central Asian markets needed to include Pakistan. And we willingly obliged. Pakistan agreed to become part of the One-Belt-One-Road (OBOR) initiative, forming the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor that includes a slew of energy projects as well as investments in roads and railways.

China's model of investing abroad soon featured Pakistan on its growth map. As we have an estimated population of over 200 million people, high consumption patterns and a relatively safer environment, this meant that China's plans to tap Europe, the Middle East and Central Asian markets needed to include Pakistan

But there is much more to this picture. China, for one, is known to make a deal when it sees one. So does it really come as a surprise that a country into which China is pumping in close to $50 billion in soft loans and investments actually has more to offer than just its location for a corridor?

CPEC has been loudly touted as a game-changer—but little else has been divulged beyond this. The Pakistanis are as inarticulate in their descriptions of it as discreet as the Chinese have been. But one thing is for certain; we will hear and see a lot of China in Pakistan than we have ever before. Their products have flooded markets in every country and their investments have only increased over time.

Pakistan isn’t the only country China has its eyes on. This year Chinese firms have already announced double the record $106 billion in foreign acquisitions they made in 2015, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. Of this, K-Electric’s transaction will be less than 1% of the overall plans to invest abroad. Lately, reports have circulated that the Chinese are interested in buying 40% of the Pakistan Stock Exchange. This comes after a Chinese company already expressed interest in buying a stake in a Pakistani cement company. So why is it that Pakistanis are still so wary of foreign investment? Is it simply because too much of it, according to our standards, is coming from one place? Or is it because we are more comfortable with American or western interest?

A recent conversation I had with an economist of a global bank swayed this way. He made a valid point; Chinese companies don’t interfere in politics, much less like the westerners do. An investment made by the US or European companies comes attached with conditions to protect human or labour rights. In this case, there will be a lot less conditionality involved. This loosely translates into saying that Pakistan can continue to function the way it does, without worrying too much about pleasing the investors. Does this make one feel better? Yes, and no.

The bigger worry is competitiveness. In the FTA signed with China, there are no prizes for guessing who came out on top in the negotiations. China got away with a lot more concessions simply because they had a lot more to offer. In the case of CPEC, Pakistan has been granting Chinese companies tax exemptions as well. In return, we are getting billions of dollars that, otherwise, would have gone elsewhere.

The bigger concern is when Chinese companies go about setting up a business, they make it really hard for inefficient entities to sustain themselves. However, for this to happen, China will have to establish itself in Pakistan a lot more than it currently has. K-Electric has no competitor and its acquisition can only mean greater efficiency given that its acquirer is an expert in the field. On the other hand, the cement industry is close to capacity utilisation and needs expansion anyway.

So for those with concerns that China will somehow control Pakistan with its finger on the button, remember that its model is to invest in countries where there is growth potential. Its own economy is headed for a slowdown and it needs its companies to find investment opportunities elsewhere. Given what we have heard about China, the situation within the country has a lot of room for improvement. Wages are low, but the Chinese government wants to increase consumption. That can’t happen unless China finds other avenues. If it does drive an entity out of business, remember that the company itself needed to be shoved out because it was uncompetitive and unsustainable. All it needed was a little push.

What Pakistan needs to concern itself with is its ability, or lack of, to evolve. Some say that CPEC is another East India Company in the making. Perhaps they are right. But the British were only able to control what was ours since we failed to transform and evolve. We wanted to continue coasting through life without raising our standards and working harder. I am not arguing that we should all necessarily start learning Mandarin, but am proposing that increasing the level of education among people and investing in quality institutions where unbiased knowledge is imparted could be a start.

If the Chinese are able to drive any of us out of business, it would be our fault?simply because we weren’t good enough.

Samir Ahmad is a business writer based in Karachi