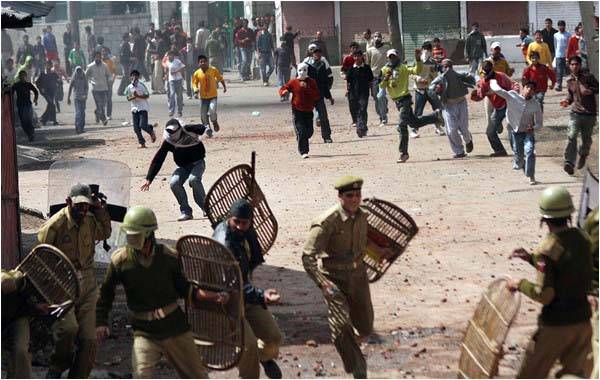

In a conversation with art critic G. Charbonnier in 1960s, French structural anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss defined modern civilization as anthropoemic or having the tendency to ‘vomit’ opponents by way of exclusions, segregations or imprisonment. He distinguished it from anthropophagic ‘primitive’ cultures, which tend to ‘devour’ their adversaries. Some three and a half decades later, liberal political theorist Benjamin D. Barber also painted the world in a binary opposition in his Jihad vs McWorld. The former represented the tribal, the barbaric and the retrograde, and the latter, the triumphant march of corporate globalization, synonymous with a spread of democracy, progress and civilization. However, the binary oppositions of Lévi-Strauss and Barber do not seem to hold much water. The “civilized” world’s linchpin—the liberal democratic political machine—not only marginalizes minority populations but also devours them through an unrestrained use of modern technologies of repression, ranging from bullets to pellets to teargas shells.

Most liberal moderns celebrate or take pride in the achievements of democracy. Not to deny the successes of democratic regimes to empower millions, but the dark underbellies of liberal democracies are seldom talked about. In our “civilized” world, dictatorships and authoritarian regimes are rightly attacked for perpetuating massive human rights violations. But democratic governments rarely get a stick for carrying out extra-judicial killings, torturing dissidents or subjecting masses to enforced disappearances and prolonged detentions, or suppressing protests by violent means.

Respected liberal thinker, Amartya Sen, writing in the Journal of Democracy in 1999, described the rise of “democracy as a universal value” to be humankind’s biggest achievement in the 20th Century. Not surprisingly, Sen’s writings on democracy or his works such as The Argumentative Indian or Identity and Violence are completely silent on Kashmiri self-determination, which is the case with most left-liberal Indian scholars theorizing on violence or identity politics in the South Asian context.

In The Argumentative Indian, Professor Sen refuses to engage with the question of Kashmir and reduces it to a footnote, which reads as: “The Kashmir issue certainly demands political attention on its own (I am not taking up that thorny question here).” Amartya Sen, generally an ardent advocate of replacing the old conception of “national security” with “human security” has rarely criticized the Indian state’s follies in Kashmir. It took 26 years of violent conflict in Kashmir for Sen to describe Kashmir as a “blot on Indian democracy”, in an interview in July this year. Like a good instrumentalist or a realist he warned about mistreating Kashmiris, which according to him, would further alienate them from India. However, he would not utter a word about Kashmiri self-determination. Humanity seems to be plagued by the binary imagination in which minorities have been reduced to the ‘primitive’ Other on a ladder of social evolutionism. The world of liberal democracy, to invoke, Indian public intellectual Shiv Viswanathan’s conceptual framework, seems to be marked by a “cognitive closure”, in which big and established state-nations are imagined as natural, and small and stateless nations are seen as somewhat unimaginable, artificial or unworthy of statehood. Old Empires are long gone but they have been succeeded by a new specie, the imperial nation-state. As Arjun Appadurai puts it: “One person’s imagined community is another man’s political prison”. Appadurai enumerates a long list of nations vying for statehood in their homelands or in diasporic spaces: Kurds, Khalistanis, Quebecois, Moros, Tamils in Sri Lanka. Kashmir does not, however, appear on his list of political prisons or stateless nations. The world of prisons and prisoners is anyways a hidden one.

In the name of national security, for preserving law and order, or in the perceived interests of a majority, liberal democracies and dictatorships alike kill and maim members of small nationalities with complete impunity. Nobody speaks of trying the heads of powerful democratic states for war crimes. Only a dictator or two of a few banana republics are occasionally punished to make us believe that human rights regimes are alive and effective. Stateless nations aspiring for statehood such as the Kashmiris, Kurds, Palestinians, and Tamils and many more are pacified militarily and the dawn of a peace is celebrated. Even though some of the liberation struggles are an outcome of incomplete decolonization, they are told that in an era of “postcolony”, the principle of national self-determination has lost its meaning. They are told to walk the road to realism and give up their struggles, which are not per se treated as movements for the deepening of democracy.

The UN, which epitomizes liberal internationalism, has since its inception treated the principle of self-determination as a genie to be bottled by emphasizing the principle of territorial integrity of states over national self-determination. The realization of self-determination, under the UN auspices, of newly independent nations like Timor-Leste, Kosovo or South Sudan has been more a function of alignment of big power interests with the aspirations of the oppressed nations rather than an outcome of a world community’s recognition and support for the principle of self-determination.

The denial of self-determination to Kashmiris despite the existence of supportive UN resolutions is one clear example of how the application of the self-determination principle has been selective and how a post-colonial state like India has morphed into an imperial nation-state. Despite ignoring the UN resolutions on Kashmir, India is clamoring for a permanent member status on the Security Council and remains hopeful of winning the support of most countries. If India gets a permanent seat, it won’t be surprising in a world where big powers invoke the principle of liberal humanitarianism selectively to suit their foreign policy interests.

Barely a week ago, on the International Day of Democracy, Ban Ki-moon exhorted the world to uphold “democracy and dignity for all”. The promise of democracy, however, sounds like a cruel joke in Kashmir, where 86 people have been killed and more than 13,000 have been injured by Indian military and paramilitary forces. The list of dead and injured is expanding. For more than two months now, Kashmir has lived under a blanket of fear, a clampdown on human movement enforced by an unending military curfew. People there now hang thick tarpaulin sheets and rugs over their windows, lest the windowpanes are smashed by Indian troops hurling stones and swinging gunstocks. Nocturnal police raids to arrest protestors have become routine and if a community resists the arrests of its youth, collective punishment is instantly meted out by India’s shock troopers: windows and doors of entire villages and towns are being smashed; men, women and children of protesting localities are being beaten with gun butts and hefty canes, some literally trampled under jackboots during late-night raids. Neighborhoods are being subjected to massive teargas shelling day and night. Pellets and bullets rain down to force the protesting Kashmiri people into silence. The Indian Central Reserve Police Force has admitted to firing 1.3 million pellets at pro-independence protestors in barely 32 days of the Kashmiri intifada, which is now in its third month.

The Indian State’s response to the pro-Azadi uprising in Kashmir has been predictable: denial of Kashmiri political agency, deployment of more troops and increase in repression; the mass uprising is treated as an outcome of Pakistani machinations or at best the handiwork of a fringe element in Kashmir; Azadi protests are described as agitational terrorism.

The State actors crack down on a entire Kashmiri populace and then urge them to uphold Kashmiryat and insaanyat as if demanding Azadi entails a loss of reason, tolerance and humanism. It is an affront to the collective intelligence of Kashmiris, both as a people and as humans.

Indian political parties, be they the present parliamentary Marxists whose elders swore by the Leninist idiom of national self-determination and its Indian variant, the Adhikari Thesis in 1940s, which recognized subcontinental Muslims as a nationality, or Nehru’s Centrist Congress Party, which took the Kashmir question to the UN in 1948 and promised a plebiscite in Kashmir, or the Hindu nationalists who have historically dreamt of squashing the Muslim majority Kashmir into submission have all united around a position that the right to self-determination has to be denied to Kashmiris at all costs. The Indian political elite supports the perpetual deployment of a massive military force to sap the Kashmiri will. The only caveat that the Indian reds insert in this overarching consensus is that Kashmiris should be treated a bit humanely and given some limited autonomy.

The Indian State’s peacemaking has historically relied on the political philosophy of Kautilya, a 4th BCE South Asian Michiavelli, to deal with nationality movements in Nagaland, Manipur and Kashmir. As Manoj Joshi, aptly put it in an ORF commentary on December 22, 2015, “Using the Kautilyan instrumentalities of Saam, Daam, Dand, Bhed (persuade, buy, punish and divide) India has largely prevailed. Often, it has not hesitated to use the policy of blood and iron, ignoring judicial due process”.

India’s recent “peace overtures”, when it sent a parliamentary delegation for “peace talks” with pro-independence leaders in detention centers, while at the same time ruling out Kashmiri self-determination, is merely a strategy to buy time and wear out Kashmiris in a long war of attrition. The logic and structure of a military occupation cannot but engender people’s resistance, which is reflected in the repeated crisis in Kashmir. It throws off balance all the carefully crafted stratagems of the Indian political-administrative-military grid in Kashmir. To contain the massive uprising, the Indian establishment shows true faith in only one strategy: force saturation, or in other words flooding and dominating the population by massive military deployment, resulting in more deaths and injuries and sedimentation of collective memories of repression.

Kashmiri deaths and injuries hardly count in a world where major liberal democracies remain insensitive to more than 400,000 Syrian deaths, where human rights questions are subordinated to geopolitical or economic interests of big powers. In a world riven by Islamophobia, the historical right of self-determination of a Muslim nationality movement like Kashmir has hardly any takers. The end of the Cold War and rise of India as a major market means that the international community, a euphemism for major world powers, treat the UN resolutions on Kashmir as cold war relics, with little or no value.

The thousands of pro-independence protests that have marked Kashmir’s length and breadth since the land and its people fell under Indian control in 1947 are not counted as the exercise of democratic will by Kashmiris. The repeated and peaceful processions in support of an independent Kashmir, which have often involved a sea of people numbering anywhere between four hundred thousand and a million people do not seem to count either as democratic expressions. The burial procession of Burhan Wani, whose death two months ago sparked the current mass uprising, was attended by some three hundred thousand people despite police curbs in many parts. In 1990, when Ashfaq Majid Wani, a major leader of the Jammu Kashmir Liberation Front was killed by Indian troops, a similar mass of three hundred thousand people attended his burial. The two burials, 26 years apart, tell us a story that the Kashmiri fervor for self-determination has remained constant. Similarly, the tradition of massive pro-self-determination marches to the offices of the UN Military Observer’s Group in Srinagar, has been another constant. Even though India and the world choose to ignore the suffering of Kashmir, the Kashmiri struggle for national self-determination, for a democratic future and dignity goes on. Kashmir and other struggles for self-determination might not garner the global media attention of an Arab Spring or a Velvet Revolution but they are integral to the development of “democracy as a universal value.”

Wajahat Ahmad is from Anantnag, India-Administered Kashmir. He teaches Sociology at OP Jindal Global University in Sonipat, India and can be reached at wahmad@jgu.edu.in

Most liberal moderns celebrate or take pride in the achievements of democracy. Not to deny the successes of democratic regimes to empower millions, but the dark underbellies of liberal democracies are seldom talked about. In our “civilized” world, dictatorships and authoritarian regimes are rightly attacked for perpetuating massive human rights violations. But democratic governments rarely get a stick for carrying out extra-judicial killings, torturing dissidents or subjecting masses to enforced disappearances and prolonged detentions, or suppressing protests by violent means.

The burial procession of Burhan Wani, whose death two months ago sparked the current mass uprising, was attended by some three hundred thousand peoples. In 1990, when Ashfaq Majid Wani of the JKLF was killed a similar mass attended his burial. The two burials, 26 years apart, tell us a story that the Kashmiri fervor for self-determination has remained constant

Respected liberal thinker, Amartya Sen, writing in the Journal of Democracy in 1999, described the rise of “democracy as a universal value” to be humankind’s biggest achievement in the 20th Century. Not surprisingly, Sen’s writings on democracy or his works such as The Argumentative Indian or Identity and Violence are completely silent on Kashmiri self-determination, which is the case with most left-liberal Indian scholars theorizing on violence or identity politics in the South Asian context.

In The Argumentative Indian, Professor Sen refuses to engage with the question of Kashmir and reduces it to a footnote, which reads as: “The Kashmir issue certainly demands political attention on its own (I am not taking up that thorny question here).” Amartya Sen, generally an ardent advocate of replacing the old conception of “national security” with “human security” has rarely criticized the Indian state’s follies in Kashmir. It took 26 years of violent conflict in Kashmir for Sen to describe Kashmir as a “blot on Indian democracy”, in an interview in July this year. Like a good instrumentalist or a realist he warned about mistreating Kashmiris, which according to him, would further alienate them from India. However, he would not utter a word about Kashmiri self-determination. Humanity seems to be plagued by the binary imagination in which minorities have been reduced to the ‘primitive’ Other on a ladder of social evolutionism. The world of liberal democracy, to invoke, Indian public intellectual Shiv Viswanathan’s conceptual framework, seems to be marked by a “cognitive closure”, in which big and established state-nations are imagined as natural, and small and stateless nations are seen as somewhat unimaginable, artificial or unworthy of statehood. Old Empires are long gone but they have been succeeded by a new specie, the imperial nation-state. As Arjun Appadurai puts it: “One person’s imagined community is another man’s political prison”. Appadurai enumerates a long list of nations vying for statehood in their homelands or in diasporic spaces: Kurds, Khalistanis, Quebecois, Moros, Tamils in Sri Lanka. Kashmir does not, however, appear on his list of political prisons or stateless nations. The world of prisons and prisoners is anyways a hidden one.

As Arjun Appadurai puts it: "One person's imagined community is another man's political prison". He lists nations vying for statehood: Kurds, Khalistanis, Quebecois, Moros, Tamils in Sri Lanka. Kashmir does not feature

In the name of national security, for preserving law and order, or in the perceived interests of a majority, liberal democracies and dictatorships alike kill and maim members of small nationalities with complete impunity. Nobody speaks of trying the heads of powerful democratic states for war crimes. Only a dictator or two of a few banana republics are occasionally punished to make us believe that human rights regimes are alive and effective. Stateless nations aspiring for statehood such as the Kashmiris, Kurds, Palestinians, and Tamils and many more are pacified militarily and the dawn of a peace is celebrated. Even though some of the liberation struggles are an outcome of incomplete decolonization, they are told that in an era of “postcolony”, the principle of national self-determination has lost its meaning. They are told to walk the road to realism and give up their struggles, which are not per se treated as movements for the deepening of democracy.

The UN, which epitomizes liberal internationalism, has since its inception treated the principle of self-determination as a genie to be bottled by emphasizing the principle of territorial integrity of states over national self-determination. The realization of self-determination, under the UN auspices, of newly independent nations like Timor-Leste, Kosovo or South Sudan has been more a function of alignment of big power interests with the aspirations of the oppressed nations rather than an outcome of a world community’s recognition and support for the principle of self-determination.

The denial of self-determination to Kashmiris despite the existence of supportive UN resolutions is one clear example of how the application of the self-determination principle has been selective and how a post-colonial state like India has morphed into an imperial nation-state. Despite ignoring the UN resolutions on Kashmir, India is clamoring for a permanent member status on the Security Council and remains hopeful of winning the support of most countries. If India gets a permanent seat, it won’t be surprising in a world where big powers invoke the principle of liberal humanitarianism selectively to suit their foreign policy interests.

Barely a week ago, on the International Day of Democracy, Ban Ki-moon exhorted the world to uphold “democracy and dignity for all”. The promise of democracy, however, sounds like a cruel joke in Kashmir, where 86 people have been killed and more than 13,000 have been injured by Indian military and paramilitary forces. The list of dead and injured is expanding. For more than two months now, Kashmir has lived under a blanket of fear, a clampdown on human movement enforced by an unending military curfew. People there now hang thick tarpaulin sheets and rugs over their windows, lest the windowpanes are smashed by Indian troops hurling stones and swinging gunstocks. Nocturnal police raids to arrest protestors have become routine and if a community resists the arrests of its youth, collective punishment is instantly meted out by India’s shock troopers: windows and doors of entire villages and towns are being smashed; men, women and children of protesting localities are being beaten with gun butts and hefty canes, some literally trampled under jackboots during late-night raids. Neighborhoods are being subjected to massive teargas shelling day and night. Pellets and bullets rain down to force the protesting Kashmiri people into silence. The Indian Central Reserve Police Force has admitted to firing 1.3 million pellets at pro-independence protestors in barely 32 days of the Kashmiri intifada, which is now in its third month.

The Indian State’s response to the pro-Azadi uprising in Kashmir has been predictable: denial of Kashmiri political agency, deployment of more troops and increase in repression; the mass uprising is treated as an outcome of Pakistani machinations or at best the handiwork of a fringe element in Kashmir; Azadi protests are described as agitational terrorism.

The State actors crack down on a entire Kashmiri populace and then urge them to uphold Kashmiryat and insaanyat as if demanding Azadi entails a loss of reason, tolerance and humanism. It is an affront to the collective intelligence of Kashmiris, both as a people and as humans.

Indian political parties, be they the present parliamentary Marxists whose elders swore by the Leninist idiom of national self-determination and its Indian variant, the Adhikari Thesis in 1940s, which recognized subcontinental Muslims as a nationality, or Nehru’s Centrist Congress Party, which took the Kashmir question to the UN in 1948 and promised a plebiscite in Kashmir, or the Hindu nationalists who have historically dreamt of squashing the Muslim majority Kashmir into submission have all united around a position that the right to self-determination has to be denied to Kashmiris at all costs. The Indian political elite supports the perpetual deployment of a massive military force to sap the Kashmiri will. The only caveat that the Indian reds insert in this overarching consensus is that Kashmiris should be treated a bit humanely and given some limited autonomy.

The Indian State’s peacemaking has historically relied on the political philosophy of Kautilya, a 4th BCE South Asian Michiavelli, to deal with nationality movements in Nagaland, Manipur and Kashmir. As Manoj Joshi, aptly put it in an ORF commentary on December 22, 2015, “Using the Kautilyan instrumentalities of Saam, Daam, Dand, Bhed (persuade, buy, punish and divide) India has largely prevailed. Often, it has not hesitated to use the policy of blood and iron, ignoring judicial due process”.

India’s recent “peace overtures”, when it sent a parliamentary delegation for “peace talks” with pro-independence leaders in detention centers, while at the same time ruling out Kashmiri self-determination, is merely a strategy to buy time and wear out Kashmiris in a long war of attrition. The logic and structure of a military occupation cannot but engender people’s resistance, which is reflected in the repeated crisis in Kashmir. It throws off balance all the carefully crafted stratagems of the Indian political-administrative-military grid in Kashmir. To contain the massive uprising, the Indian establishment shows true faith in only one strategy: force saturation, or in other words flooding and dominating the population by massive military deployment, resulting in more deaths and injuries and sedimentation of collective memories of repression.

Kashmiri deaths and injuries hardly count in a world where major liberal democracies remain insensitive to more than 400,000 Syrian deaths, where human rights questions are subordinated to geopolitical or economic interests of big powers. In a world riven by Islamophobia, the historical right of self-determination of a Muslim nationality movement like Kashmir has hardly any takers. The end of the Cold War and rise of India as a major market means that the international community, a euphemism for major world powers, treat the UN resolutions on Kashmir as cold war relics, with little or no value.

The thousands of pro-independence protests that have marked Kashmir’s length and breadth since the land and its people fell under Indian control in 1947 are not counted as the exercise of democratic will by Kashmiris. The repeated and peaceful processions in support of an independent Kashmir, which have often involved a sea of people numbering anywhere between four hundred thousand and a million people do not seem to count either as democratic expressions. The burial procession of Burhan Wani, whose death two months ago sparked the current mass uprising, was attended by some three hundred thousand people despite police curbs in many parts. In 1990, when Ashfaq Majid Wani, a major leader of the Jammu Kashmir Liberation Front was killed by Indian troops, a similar mass of three hundred thousand people attended his burial. The two burials, 26 years apart, tell us a story that the Kashmiri fervor for self-determination has remained constant. Similarly, the tradition of massive pro-self-determination marches to the offices of the UN Military Observer’s Group in Srinagar, has been another constant. Even though India and the world choose to ignore the suffering of Kashmir, the Kashmiri struggle for national self-determination, for a democratic future and dignity goes on. Kashmir and other struggles for self-determination might not garner the global media attention of an Arab Spring or a Velvet Revolution but they are integral to the development of “democracy as a universal value.”

Wajahat Ahmad is from Anantnag, India-Administered Kashmir. He teaches Sociology at OP Jindal Global University in Sonipat, India and can be reached at wahmad@jgu.edu.in