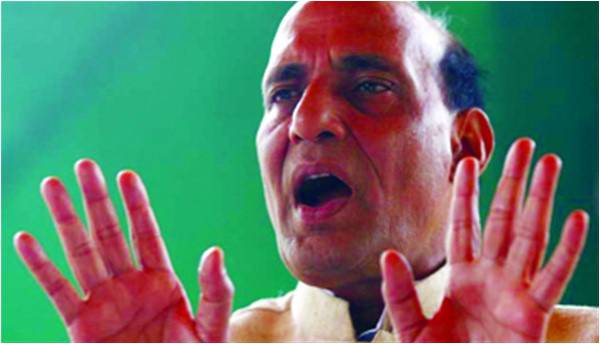

As Kashmir continues to burn, without even a little attention from New Delhi, an opportunity to put out the fire that came in the shape of Indian Home Minister Rajnath Singh’s visit to Pakistan was also allowed to slip. There has been no letup in the tensions in Kashmir for a month now, and the violence has claimed nearly 60 lives with thousands injured. And it has a lot with the absence of political engagement, thus making it an issue of internal dimension. The fact is that Pakistan cannot be wished away when it comes to a smoldering conflict like this, especially when India repeatedly blames Islamabad for “all the trouble” in Kashmir.

When Rajnath Singh visited Islamabad to attend the SAARC interior ministers conference, political observers who have watched Kashmir for a long time, and are concerned about the situation, saw it as a glimmer of hope. The conference certainly was about the interior affairs of the countries of the region, but it came at a when New Delhi is either helpless, or is deliberately ignoring the fact that this political turmoil needs to be controlled to save Kashmir from further erosion of order. India and Pakistan both upped the ante on Kashmir, albeit without referring to it directly, and also made terrorism the focus. That has obviously been like a thorn in the relations between the two neighbours. While New Delhi has been maintaining for a long time that talks and terror cannot go together, Prime Minister Narendra Modi surprised his detractors by visiting Lahore in December last year. The Pathankot attack did take place after the visit, but the bonhomie did not seem to fade out until Rajnath Singh’s latest visit.

When Kashmir erupted with a renewed call for “Azadi”, Pakistan was caught unaware, and for the first few days after Hizbul Mujahideen commander Burhan Wani’s killing, the volcanic response was not even noticed. Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif made a call to observe a “Black Day” much later. And the day Singh arrived in Islamabad, Sharif spoke of freedom for Kashmiris.

Political analysts said the prime minister had made the move to win some more seats from the Pakistan People’s Party (PPP) in Pakistan-administered Kashmir in the elections on July 21, and eventually the Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz won with a handsome majority.

That does not concur with the ground situation, because the PML-N’s return to power was a forgone conclusion much before that. The help from the “Black Day” call might have been marginal. The results had been correctly predicted since last year. Nawaz Sharif was questioned cornered by the opposition, perhaps even a section of the establishment, and the extremists, on his silence over the mayhem in Kashmir that followed Wani’s death. But he probably went overboard.

When Rajnath Singh was in Islamabad, the way two prominent faces of the militant struggle –Hafiz Saeed and Hizbul Mujahideen supreme commander Syed Salahuddin – were almost allowed to parade to oppose the visit did not help make the SAARC meeting conducive for any positive engagement. New Delhi took offence, and countered Pakistan’s repeated argument that the Kashmiri movement was indigenous. By allowing the commander of a militant organization to openly carry out a sit in, it also called into question its repeated claim that it only supports the Kashmiri cause by diplomatic, moral and political means. Today’s uprising in Kashmir is undoubtedly spontaneous and indigenous, but certain actions allowed by Islamabad helped the hawks in India to construct a narrative that it was all about terrorism and was only Pakistan sponsored. It seems that it was a panic reaction by Pakistan to respond in this fashion, as flip-flop has become the hallmark of Pakistan’s Kashmir policy. The Kashmir fatigue has dominated the Pakistani narrative for long time and it has also angered Kashmiris who had been feeling that they were pushed to violence by Pakistan in the 1990s.

A better strategy could have been for the Pakistan civil society to come forward and meet Singh to express their concerns. People like Asma Jehangir and IA Rehman, and organizations such Pakistan-India People’s Forum for Peace and Democracy (PIPFDP), Pakistan Institute of Legislative Development and Transparency (PILDAT) and the South Asia Free Media Forum, who have been active on track-2, had the responsibility to raise concerns over what is happening in Kashmir. But they failed in fulfilling that responsibility and have left the space open for radicals.

Moreover, reports about Islamabad not treating Singh in accordance with diplomatic norms did not go well in the longer paradigm of relations, which need to be seen as working, if not friendly. The reported absence of Pakistani Interior Minister Chaudhry Nisar from the lunch is not in line with the South Asian traditions of hospitality, and such behaviour is not warranted if the two countries have to work together and resolve mutual issues.

On the other hand, New Delhi is also not ready to recognize the political reasons behind the unrest. The Bhartiya Janata Party is part of the coalition government with the People’s Democratic Party led by Mehbooba Mufti, but the state government has failed miserably to overcome the challenge of restoring order even to a semblance of normalcy. The BJP had committed to addressing the issue politically as per the Agenda of Alliance it had agreed on with the PDP, and that includes dialogue with both Pakistan and the separatists. But that seems to be a distant dream, when the government is not even showing remorse over the loss of lives, mostly young people, because of shooting carried out by the police and paramilitary forces. This is the first time Kashmir has been under such a severe curfew for 30 days. The number of injured, that is nearly 6,000, is also unprecedented.

Today’s Kashmir requires a political outreach that could open up news windows of engagement. The politicisation of Kashmir, both by Pakistan and India, will not help get it out of this deepening crisis. The Indian government may be waiting for the masses to tire out, but they have given enough indications in one month that they are ready for a long haul. In that case, will Mehbooba Mufti’s government survive? Or will it have a moral standing to remain in power? And if it becomes difficult for the state government to hold on to power, New Delhi will lose a political face in Kashmir. The consequences will be very difficult to deal with.

The author is a veteran journalist from Srinagar and the editor-in-chief of

The Rising Kashmir

When Rajnath Singh visited Islamabad to attend the SAARC interior ministers conference, political observers who have watched Kashmir for a long time, and are concerned about the situation, saw it as a glimmer of hope. The conference certainly was about the interior affairs of the countries of the region, but it came at a when New Delhi is either helpless, or is deliberately ignoring the fact that this political turmoil needs to be controlled to save Kashmir from further erosion of order. India and Pakistan both upped the ante on Kashmir, albeit without referring to it directly, and also made terrorism the focus. That has obviously been like a thorn in the relations between the two neighbours. While New Delhi has been maintaining for a long time that talks and terror cannot go together, Prime Minister Narendra Modi surprised his detractors by visiting Lahore in December last year. The Pathankot attack did take place after the visit, but the bonhomie did not seem to fade out until Rajnath Singh’s latest visit.

The Pakistani civil society should have met the Indian home minister

When Kashmir erupted with a renewed call for “Azadi”, Pakistan was caught unaware, and for the first few days after Hizbul Mujahideen commander Burhan Wani’s killing, the volcanic response was not even noticed. Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif made a call to observe a “Black Day” much later. And the day Singh arrived in Islamabad, Sharif spoke of freedom for Kashmiris.

Political analysts said the prime minister had made the move to win some more seats from the Pakistan People’s Party (PPP) in Pakistan-administered Kashmir in the elections on July 21, and eventually the Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz won with a handsome majority.

That does not concur with the ground situation, because the PML-N’s return to power was a forgone conclusion much before that. The help from the “Black Day” call might have been marginal. The results had been correctly predicted since last year. Nawaz Sharif was questioned cornered by the opposition, perhaps even a section of the establishment, and the extremists, on his silence over the mayhem in Kashmir that followed Wani’s death. But he probably went overboard.

When Rajnath Singh was in Islamabad, the way two prominent faces of the militant struggle –Hafiz Saeed and Hizbul Mujahideen supreme commander Syed Salahuddin – were almost allowed to parade to oppose the visit did not help make the SAARC meeting conducive for any positive engagement. New Delhi took offence, and countered Pakistan’s repeated argument that the Kashmiri movement was indigenous. By allowing the commander of a militant organization to openly carry out a sit in, it also called into question its repeated claim that it only supports the Kashmiri cause by diplomatic, moral and political means. Today’s uprising in Kashmir is undoubtedly spontaneous and indigenous, but certain actions allowed by Islamabad helped the hawks in India to construct a narrative that it was all about terrorism and was only Pakistan sponsored. It seems that it was a panic reaction by Pakistan to respond in this fashion, as flip-flop has become the hallmark of Pakistan’s Kashmir policy. The Kashmir fatigue has dominated the Pakistani narrative for long time and it has also angered Kashmiris who had been feeling that they were pushed to violence by Pakistan in the 1990s.

A better strategy could have been for the Pakistan civil society to come forward and meet Singh to express their concerns. People like Asma Jehangir and IA Rehman, and organizations such Pakistan-India People’s Forum for Peace and Democracy (PIPFDP), Pakistan Institute of Legislative Development and Transparency (PILDAT) and the South Asia Free Media Forum, who have been active on track-2, had the responsibility to raise concerns over what is happening in Kashmir. But they failed in fulfilling that responsibility and have left the space open for radicals.

Moreover, reports about Islamabad not treating Singh in accordance with diplomatic norms did not go well in the longer paradigm of relations, which need to be seen as working, if not friendly. The reported absence of Pakistani Interior Minister Chaudhry Nisar from the lunch is not in line with the South Asian traditions of hospitality, and such behaviour is not warranted if the two countries have to work together and resolve mutual issues.

On the other hand, New Delhi is also not ready to recognize the political reasons behind the unrest. The Bhartiya Janata Party is part of the coalition government with the People’s Democratic Party led by Mehbooba Mufti, but the state government has failed miserably to overcome the challenge of restoring order even to a semblance of normalcy. The BJP had committed to addressing the issue politically as per the Agenda of Alliance it had agreed on with the PDP, and that includes dialogue with both Pakistan and the separatists. But that seems to be a distant dream, when the government is not even showing remorse over the loss of lives, mostly young people, because of shooting carried out by the police and paramilitary forces. This is the first time Kashmir has been under such a severe curfew for 30 days. The number of injured, that is nearly 6,000, is also unprecedented.

Today’s Kashmir requires a political outreach that could open up news windows of engagement. The politicisation of Kashmir, both by Pakistan and India, will not help get it out of this deepening crisis. The Indian government may be waiting for the masses to tire out, but they have given enough indications in one month that they are ready for a long haul. In that case, will Mehbooba Mufti’s government survive? Or will it have a moral standing to remain in power? And if it becomes difficult for the state government to hold on to power, New Delhi will lose a political face in Kashmir. The consequences will be very difficult to deal with.

The author is a veteran journalist from Srinagar and the editor-in-chief of

The Rising Kashmir