Today we inhabit a world where ‘monolithic’ identities - like those created by nation-states - provide the basis for the global system of economics, politics and administration. The idea of the nation state first emerged in the particular historical context of Europe, but it has exceeded its origin by influencing “Other” societies to relinquish their traditional and organic identities for the meta-identity of a ‘nation’. Historically, different cultures interacted with each other and influenced different spheres of life more freely. Ideally, such a healthy interaction can take place where power relations do not tilt heavily towards one group at the expense of others. The notion of the modern state among non-western societies took roots in a period where the balance of power between the colonial powers and “Others” was totally in favour of the former. This situation forced the subjugated societies to base their identities on principles which were Eurocentric. As a result, the diversities within were subsumed under the rubric of ‘national identity’.

In the context of India and Pakistan both countries have followed the path of their masters. In their zeal for the unified identity they embarked upon a nation building project which pathologically abhorred any local identity that does not fit within the meta-identity of the nation state. With the help of different institutions of the state, the ruling elites and ideologues made institutional arrangements, which structurally suppressed local narratives and politics of identity. A corollary of the structural violence appeared in the shape of tendencies that base identity markers on sources within local culture.

In Pakistan Sindhi, Bengali, Baloch and Pashtun nationalisms reject the collective identity for the sake of an identity based on language. In the post-colonial period, the foci of analysis regarding nationalism remain on regional varieties, not local ones. So far the debate regarding nationalist movements within Pakistan has focused on broad nationalist tendencies at provincial or regional level. This meta-narrative of provincial nationalism rides roughshod over the aspirations of minor identities within and tried to subsume these under the category of geographic nationalism where majoritarian politics defines the identities of minority linguistic or cultural groups.

Provincial nationalism rides roughshod over the aspirations of minor identities within

At the core of narratives of regional nationalism in Pakistan lies geography. It is not some divine order but geography which turns a very profane affair like identity into a sacred idea.

Torwali speakers inhabit the region of Bahrain in Swat Kohistan. They belong to the Dardic group of languages and race. But historical development has severed their relationship with people of their own language family. In the particular socioeconomic and political setting of Pakistan, communities living on the peripheries of a centralised state are always ignored by those controlling the reins of power. In such a situation, Zubair Torwali has made it his life’s work to empower the marginalised community of Torwali speakers through the power of the pen and development initiatives. Given the rising tide of religious extremism, Zubair Torwali has also directed his pen against extremist and violent groups in society. His views and opinions about politics, identity debates, militancy, education, progress and economy appeared in different newspapers, weeklies, online magazines and research journals over a period of seven years.

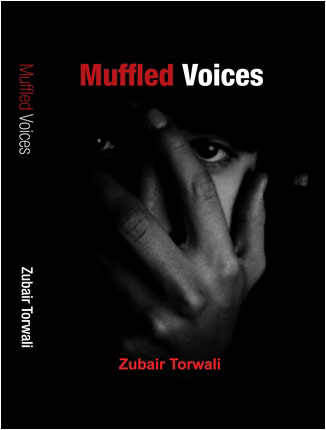

This time his scattered views are compiled and published in a book named “Muffled Voices: Longing for a pluralist and peaceful Pakistan” published by Multi Line Publications, Lahore.

The chapter on Swat provides an insider’s view about the conflict as the writer explicates the ravages of Taliban militancy in Swat.

He seems to disapprove of most of the commentaries on Swat in particular and Pashtun culture in general because of the trend to derive their conclusions from premises of stereotypes. Hence, the collective failure of the Pakistani state as well as Pakistani intelligentsia to diagnose the ailment. In the Afghan Jihad, Strategic Depth and War on Terror, the players of the New Great Game never bothered about the actual people of the region.

His overall theoretical framework in analysing extremism, religion, society, language and other political and economic issues is mostly informed by secularism. However, over-reliance on the universal model of secularism bars him from examining the local dynamics that defy the meta-narratives of theoretical unity provided by secularism. Modern radical Islam has increasingly destroyed the space for local narratives of religion.

Zubair Torwali is at his best when it comes to his forte - minority langauges and indigenous cultures. His surname derives from ‘Torwali’ which is one of the minority languages in Pakistan. This is basically an oral language. Therefore, the contours of Torwali culture have all the bearings typical of an oral culture. At the same time it faces the same challenges that are faced by oral cultures thanks to modernity, where the written word is a symbol for the whole structure of the state. Torwalis, like other minority language communities, do not have a say in decision and policy-making bodies in Pakistan. As a corollary, the historical and collective memory along with indigenous knowledge is rapidly vanishing.

In a highly globalised world, small cultures face future shock if they are not equipped with required tricks of the trade. Exposure of such cultures to highly advanced societies that have support of economic prowess and cultural industry are in danger of vanishing from the face of earth. The day will not be far away when our world will turn into graveyard of languages. Zubair’s efforts to bring the issues of vanishing languages and cultures into the centre stage of identity discourse in Pakistan through practice and pen are laudable. The kind of history we have manufactured and the narrative of identity we have constructed has failed to unite multiple identities under the single rubric of a nation. In Pakistan there is a dire need to rehabilitate peripheral voices on the pages of history and intellectual milieu.

Zubair realizes the perils of losing a culturally rooted worldview and language. His views and suggestion for the preservation of minority langauges speaks for his empathy and understanding of the local dynamics that are changing under the pressure of modernisation and globalisation. Being a speaker of a Dardic language in Gilgit-Baltistan, I feel intellectual and existential affinity with Zubair’s views and plans regarding language rights and preservation.

However, the book suffers from flaws that make it a difficult read. The book comprises three parts. It would have been better if the writer had provided readers with a brief introduction of each section so that the readers could situate the debate in its proper context. There is no doubt that a lot of thought went into the writing of the articles and that are compiled in the book, but less time and effort has been invested in the stage of compilation.

Zubair Towarli’s book “Muffled Voices” is a loud protest against the structural violence meted out by the power centres to the communities inhabiting the margins of national history and narrative.

Aziz Ali Dad is a social scientist and columnist