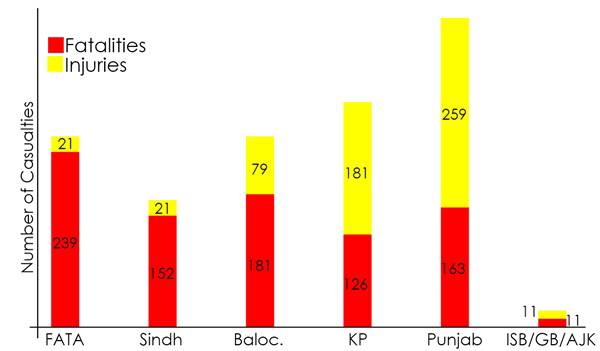

The National Action Plan (NAP) was designed to root out extremism in the country in all forms, be it insurgency in Balochistan, militancy in the federally administered tribal areas (FATA) and adjoining areas, or urban crime syndicates in Karachi. The national effort was directed towards securing the lives of citizens and establishing peace in the land. In this backdrop, it is surprising to see the province of Punjab marred by such an unusual amount of violence in the first quarter of 2016.

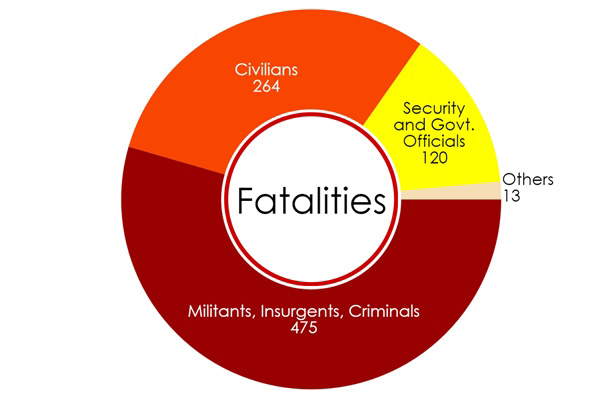

A total of 163 people lost their lives in Punjab between January and March – a 101.2% rise over the same period from 2015, according to the Q1 security report by the Center for Research and Security Studies (CRSS). There are two reasons for this sudden upsurge of violence in Pakistan’s largest province.

First, Pakistan has grown exceptionally good at eliminating the extremist threat by force in other parts of the country. Whether it is the military operation in North Waziristan, or the insurgent mollification in Balochistan, or the urban pacification in Karachi, 2015 showed a significant decline in violence-related fatalities across the country. Pakistan’s inability to target and eliminate the radical ideology that fuels these extremists is a debate for another time, but this level of law enforcement in various parts of Pakistan shrunk the space for militants to operate freely out of their hideouts. Analysts and data researchers have long lamented the lack of government focus in Punjab to curb militancy, and issued dire warnings of pending carnage should the radical element set its sights on Punjab.

Second, the worst incident of violence in Punjab in the recent months was a bombing at Lahore’s Gulshan-e-Iqbal Park on March 27. The attack ostensibly targeted Christians on Easter, resulting in at least 72 deaths, many of them Muslim children. Since the horrendous attack on schoolchildren at the Army Public School (APS) in Peshawar, the precipitating event for the NAP, extremists have attempted to target children. Of the 72 dead in the attack, 29 were schoolchildren.

The Easter attack was seen as an attack on minorities, but the data disagrees. There had been a trend among extremist groups to target minorities in order to stay relevant and secure recruitment and funding. However, with shrinking space, these attempts have largely been thwarted. In fact, the number of deaths resulting from sectarian violence was nearly half of those in the comparable period of 2015. Major sectarian groups like Jundullah and Lashkar-e-Jhangvi did not claim any attacks in this quarter, which is another indication of the tightening noose.

The situation may be improving on the whole when the data is measured against the first quarter of 2015. However, it must be stated that all quarters in 2015 showed a decline in violence-related fatalities. Compared with the last quarter of 2015, there is a near 10% rise in violence in the first quarter of 2016. Statistically, this is not overly alarming, as spikes can occur every now and then. But if this trend holds for the coming months, Pakistan faces the risk of teetering back into the chaos.

The author is a journalist and a senior research fellow at the Center for Research and Security Studies, Islamabad

A total of 163 people lost their lives in Punjab between January and March – a 101.2% rise over the same period from 2015, according to the Q1 security report by the Center for Research and Security Studies (CRSS). There are two reasons for this sudden upsurge of violence in Pakistan’s largest province.

First, Pakistan has grown exceptionally good at eliminating the extremist threat by force in other parts of the country. Whether it is the military operation in North Waziristan, or the insurgent mollification in Balochistan, or the urban pacification in Karachi, 2015 showed a significant decline in violence-related fatalities across the country. Pakistan’s inability to target and eliminate the radical ideology that fuels these extremists is a debate for another time, but this level of law enforcement in various parts of Pakistan shrunk the space for militants to operate freely out of their hideouts. Analysts and data researchers have long lamented the lack of government focus in Punjab to curb militancy, and issued dire warnings of pending carnage should the radical element set its sights on Punjab.

Second, the worst incident of violence in Punjab in the recent months was a bombing at Lahore’s Gulshan-e-Iqbal Park on March 27. The attack ostensibly targeted Christians on Easter, resulting in at least 72 deaths, many of them Muslim children. Since the horrendous attack on schoolchildren at the Army Public School (APS) in Peshawar, the precipitating event for the NAP, extremists have attempted to target children. Of the 72 dead in the attack, 29 were schoolchildren.

The Easter attack was seen as an attack on minorities, but the data disagrees. There had been a trend among extremist groups to target minorities in order to stay relevant and secure recruitment and funding. However, with shrinking space, these attempts have largely been thwarted. In fact, the number of deaths resulting from sectarian violence was nearly half of those in the comparable period of 2015. Major sectarian groups like Jundullah and Lashkar-e-Jhangvi did not claim any attacks in this quarter, which is another indication of the tightening noose.

The situation may be improving on the whole when the data is measured against the first quarter of 2015. However, it must be stated that all quarters in 2015 showed a decline in violence-related fatalities. Compared with the last quarter of 2015, there is a near 10% rise in violence in the first quarter of 2016. Statistically, this is not overly alarming, as spikes can occur every now and then. But if this trend holds for the coming months, Pakistan faces the risk of teetering back into the chaos.

The author is a journalist and a senior research fellow at the Center for Research and Security Studies, Islamabad