On an eventful September morning in 2012, an English king’s bones were discovered under a car park in Leicester. Images of a delicate skeleton half protruding from the brown earth made their rounds on the television screens as historians and forensic scientists and probably everyone English gabbled excitedly about the discovery. The king in question was Richard lll, one of English history’s most colourful figures, to say the least. Till the unearthing of his remains, from which the heroism of his final battle was pieced together, Richard had been widely painted as a grotesque, scheme-hatching, nephew-murdering monster who famously yelled ‘A horse, a horse, my kingdom for a horse!’ in one of the Bard’s most gripping, albeit slightly biased, plays.

British Poet Laureate, Carol Ann Duffy, composed a poem last year on the occasion of the king’s re-interment - a little ditty that reads like a shudder. She likens the exhumed bones to words telling a story; her voice is the voice of Richard, cold and faraway, requesting - with the calm dignity of a defeated king - a new narration, a kinder narration, to accompany the reburial.

My bones, scripted in light, upon cold soil,

a human braille. My skull, scarred by a crown,

emptied of history. Describe my soul

as incense, votive, vanishing; your own

the same. Grant me the carving of my name.

These relics, bless. Imagine you re-tie

a broken string and on it thread a cross,

the symbol severed from me when I died.

The end of time - an unknown, unfelt loss -

unless the Resurrection of the Dead…

or I once dreamed of this, your future breath

in prayer for me, lost long, forever found;

or sensed you from the backstage of my death,

as kings glimpse shadows on a battleground.

The poem, so powerfully visual, packs within its three stanzas the epic drama that was the rediscovery and reappraisal of a long vilified monarch. Archaeology wields this magic. It can change the world, or our perception of it, in one glorious moment of unveiling. It is our closest, truest tie to history. It illustrates, faithfully, and does not caricaturise the stories and figures from our pasts. It tosses up dinosaurs, mammoths, and monsters among men. And under its scientific light, the bits of heroes in these monsters breathe again. The saga of Richard lll’s findings is just one among many instances of archaeological activity lending to literary or artistic creation.

In fact, according to archaeologist Colin Renfrew in Figuring It Out: The Parallel Visions of Artists and Archaeologists, archaeology not only triggers creative thinking, it can be seen as analogous to it. Archaeologists, by upending sediments of time and mystery to get to the past, strive as much as visual artists to observe their surroundings, understand who we are and how we interact with the world. And confronting an ancient monument or relic, Renfrew writes, is the same as confronting a work of art in a gallery. No viewer can ever get at the complete meaning of either, but the confrontation leaves him, nonetheless, in a sort of sweet unrest and with the feeling of having glimpsed some larger reality.

Using examples like British sculptor Richard Long, Renfrew draws on the similarities between an archaeologist’s exploration of the physical universe (to answer questions that pertain even to the spiritual) and a contemporary artist’s. Long’s arcane, circular arrangements of rocks in a gallery speak as much of human presence in, and engagement with, the material world as do any number of quiet, bewitching, Neolithic tools and figurines in a museum. In the same manner, many works by Scottish poet and artist Ian Hamilton Finlay evoke the steles and tablets of the ancient world that carry some of the earliest examples of writing on them. Finlay would inscribe, mostly in a commanding, neoclassical font, edictal phrases on stone slabs and scatter them among his labyrinthine garden like remnants of some old and mighty order. He would thus not only mimic archaeology and epigraphy but also invert them by taking the faux cryptographs out into the open (archaeological protocol brings objects in, into glass cases, inside rooms).

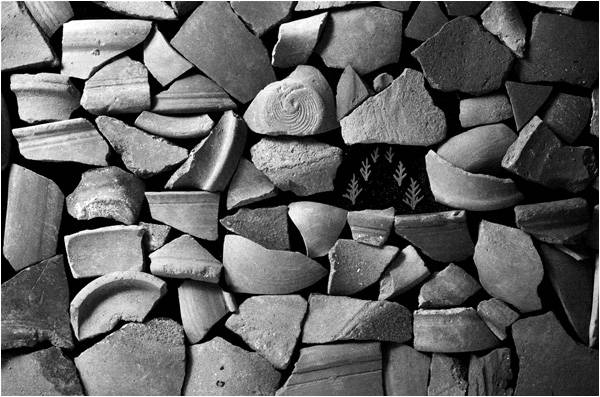

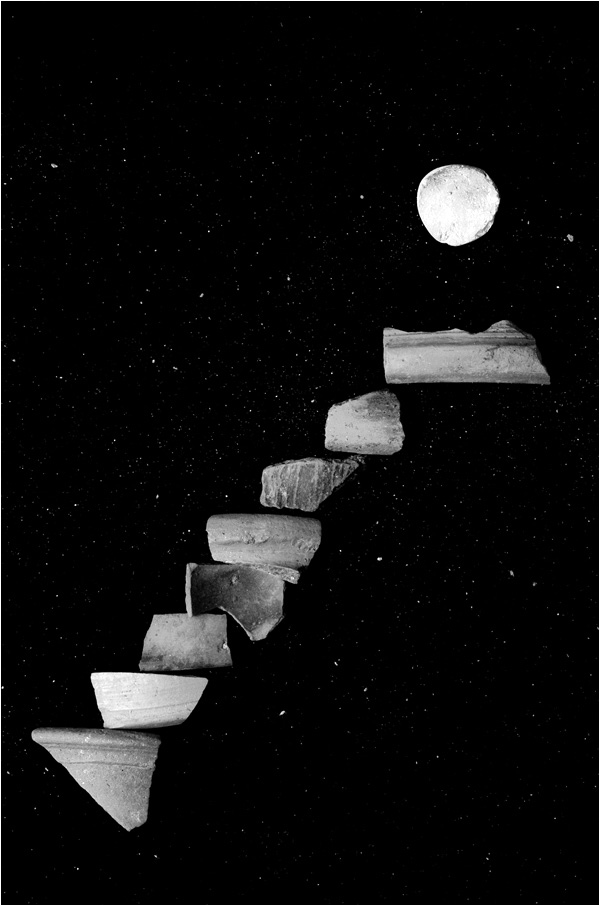

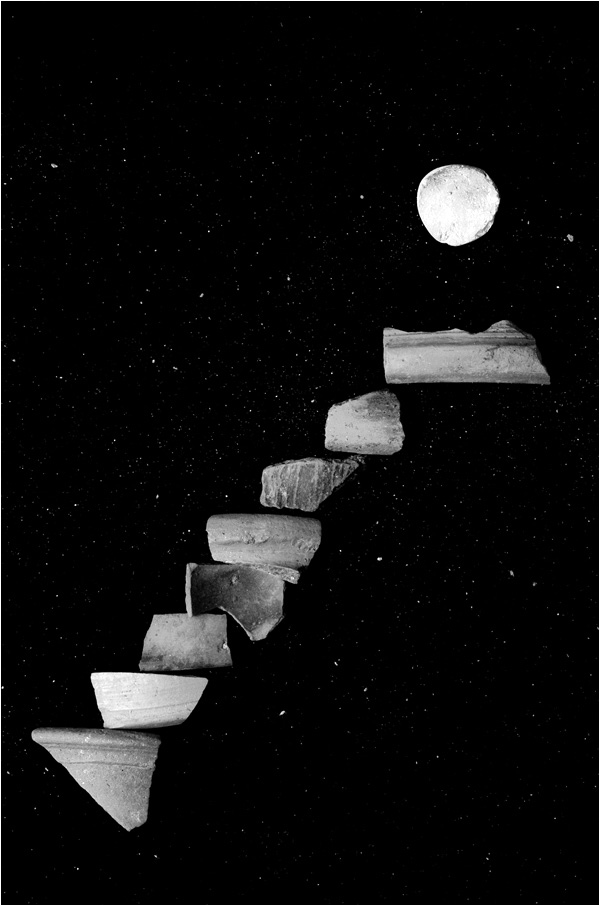

As akin as they may seem, however, to the process of excavating the past, works by Long or Finlay are not products of that process. Looking at, and using, archaeological investigation itself as art is something a young photographer from Lahore has been doing to wonderful effect. Aurangzaib Khan has been working as a photographer with the Italian Archaeological Mission in Swat for four years. In 2013, while photographing some excavated pottery, Khan came across an artefact that looked like a bird to him. In the solitude and confinement of his workspace at night, facing this strange antiquity that had just been salvaged, Khan decided to build on the resemblance it bore to a bird and made it fly towards a terracotta moon. This was the springboard for a whimsical series of digital works by Khan, which see fragments of ancient pottery arrange themselves as primordial images in front of a star-dusted backdrop. A show of these works was held in November, 2015, at Lahore’s Taseer Art Gallery.

Shards and pieces form, one after the other, a rustic wall beneath a crescent moon; an enormous ant in the sky - haloed by a cluster of flowers; a playfully simple clay car clunking its way across galaxies; a mythic female silhouetted in relief against the heavens, like a deity from an embryonic dream; a two-dimensional mountain range; a surreal and suspended stairway; and a giant, solemn fish, gliding dreamily through the night. Khan not only reanimates, like a shaman, the broken findings, but brings experiential elements to his reconstructions of them. The clumsy, airborne vehicle, for example, is inspired by a car that he heard driving through the slumbering valley late one night, filling the silent landscape with sound and strangely reassuring him. Most of the other images are dense with the revelatory power of the night sky - something he, again, became increasingly aware of during his nocturnal work hours in Swat.

Interestingly, in a move both poetic and resourceful, Khan uses the dust on and around these objects for the starry skies in the pictures. Now, dust, despite all its invasiveness, is an enigmatic phenomenon that carries with itself a strong sense of time passing. ‘As it sticks to our fingertips, dust propels a vague state of retrospection, carrying us on its supple wings,’ writes Celeste Olalquiaga in The Artificial Kingdom: A Treasury of the Kitsch Experience. Dust, Olalquiaga claims, ‘grants things a peculiarity that reconstitutes them as a new experience, validating instead of disqualifying them.’ Khan, too, seems to have seen the dust on the artefacts as more than just a layer to get past; he must have seen it as infused with the same transcendence as the objects it covered. The usual associations of dust and debris with chaos and confusion are challenged by Khan as he uses both to make sense of the past.

There is a beauty in fragments that sometimes eludes intact objects, histories, stories. Consider the poetry of Sappho, surviving in broken verses, having been preserved, destroyed, and resurrected piecemeal. Even in images, the fragments of papyrus bearing her stray lyrics look wise, knowing, and timeless. They escape the close-fitting comfort of a single meaning, forever inviting readers and viewers to try to fill in the gaps. Aurangzaib Khan, in his modest, exciting series of black and white photographs, summons long-dead potters, their creations, the little homes in the little villages they must have adorned, the husbands and wives and children who would eat and drink from them. He summons a past both local and grand, taking everything he needs from just one archaeological dig under the stars.

Dua Abbas Rizvi is a visual artist and writer

British Poet Laureate, Carol Ann Duffy, composed a poem last year on the occasion of the king’s re-interment - a little ditty that reads like a shudder. She likens the exhumed bones to words telling a story; her voice is the voice of Richard, cold and faraway, requesting - with the calm dignity of a defeated king - a new narration, a kinder narration, to accompany the reburial.

My bones, scripted in light, upon cold soil,

a human braille. My skull, scarred by a crown,

emptied of history. Describe my soul

as incense, votive, vanishing; your own

the same. Grant me the carving of my name.

These relics, bless. Imagine you re-tie

a broken string and on it thread a cross,

the symbol severed from me when I died.

The end of time - an unknown, unfelt loss -

unless the Resurrection of the Dead…

or I once dreamed of this, your future breath

in prayer for me, lost long, forever found;

or sensed you from the backstage of my death,

as kings glimpse shadows on a battleground.

The poem, so powerfully visual, packs within its three stanzas the epic drama that was the rediscovery and reappraisal of a long vilified monarch. Archaeology wields this magic. It can change the world, or our perception of it, in one glorious moment of unveiling. It is our closest, truest tie to history. It illustrates, faithfully, and does not caricaturise the stories and figures from our pasts. It tosses up dinosaurs, mammoths, and monsters among men. And under its scientific light, the bits of heroes in these monsters breathe again. The saga of Richard lll’s findings is just one among many instances of archaeological activity lending to literary or artistic creation.

Khan reanimates, like a shaman, the broken shards and discoveries

In fact, according to archaeologist Colin Renfrew in Figuring It Out: The Parallel Visions of Artists and Archaeologists, archaeology not only triggers creative thinking, it can be seen as analogous to it. Archaeologists, by upending sediments of time and mystery to get to the past, strive as much as visual artists to observe their surroundings, understand who we are and how we interact with the world. And confronting an ancient monument or relic, Renfrew writes, is the same as confronting a work of art in a gallery. No viewer can ever get at the complete meaning of either, but the confrontation leaves him, nonetheless, in a sort of sweet unrest and with the feeling of having glimpsed some larger reality.

Using examples like British sculptor Richard Long, Renfrew draws on the similarities between an archaeologist’s exploration of the physical universe (to answer questions that pertain even to the spiritual) and a contemporary artist’s. Long’s arcane, circular arrangements of rocks in a gallery speak as much of human presence in, and engagement with, the material world as do any number of quiet, bewitching, Neolithic tools and figurines in a museum. In the same manner, many works by Scottish poet and artist Ian Hamilton Finlay evoke the steles and tablets of the ancient world that carry some of the earliest examples of writing on them. Finlay would inscribe, mostly in a commanding, neoclassical font, edictal phrases on stone slabs and scatter them among his labyrinthine garden like remnants of some old and mighty order. He would thus not only mimic archaeology and epigraphy but also invert them by taking the faux cryptographs out into the open (archaeological protocol brings objects in, into glass cases, inside rooms).

As akin as they may seem, however, to the process of excavating the past, works by Long or Finlay are not products of that process. Looking at, and using, archaeological investigation itself as art is something a young photographer from Lahore has been doing to wonderful effect. Aurangzaib Khan has been working as a photographer with the Italian Archaeological Mission in Swat for four years. In 2013, while photographing some excavated pottery, Khan came across an artefact that looked like a bird to him. In the solitude and confinement of his workspace at night, facing this strange antiquity that had just been salvaged, Khan decided to build on the resemblance it bore to a bird and made it fly towards a terracotta moon. This was the springboard for a whimsical series of digital works by Khan, which see fragments of ancient pottery arrange themselves as primordial images in front of a star-dusted backdrop. A show of these works was held in November, 2015, at Lahore’s Taseer Art Gallery.

Shards and pieces form, one after the other, a rustic wall beneath a crescent moon; an enormous ant in the sky - haloed by a cluster of flowers; a playfully simple clay car clunking its way across galaxies; a mythic female silhouetted in relief against the heavens, like a deity from an embryonic dream; a two-dimensional mountain range; a surreal and suspended stairway; and a giant, solemn fish, gliding dreamily through the night. Khan not only reanimates, like a shaman, the broken findings, but brings experiential elements to his reconstructions of them. The clumsy, airborne vehicle, for example, is inspired by a car that he heard driving through the slumbering valley late one night, filling the silent landscape with sound and strangely reassuring him. Most of the other images are dense with the revelatory power of the night sky - something he, again, became increasingly aware of during his nocturnal work hours in Swat.

Interestingly, in a move both poetic and resourceful, Khan uses the dust on and around these objects for the starry skies in the pictures. Now, dust, despite all its invasiveness, is an enigmatic phenomenon that carries with itself a strong sense of time passing. ‘As it sticks to our fingertips, dust propels a vague state of retrospection, carrying us on its supple wings,’ writes Celeste Olalquiaga in The Artificial Kingdom: A Treasury of the Kitsch Experience. Dust, Olalquiaga claims, ‘grants things a peculiarity that reconstitutes them as a new experience, validating instead of disqualifying them.’ Khan, too, seems to have seen the dust on the artefacts as more than just a layer to get past; he must have seen it as infused with the same transcendence as the objects it covered. The usual associations of dust and debris with chaos and confusion are challenged by Khan as he uses both to make sense of the past.

There is a beauty in fragments that sometimes eludes intact objects, histories, stories. Consider the poetry of Sappho, surviving in broken verses, having been preserved, destroyed, and resurrected piecemeal. Even in images, the fragments of papyrus bearing her stray lyrics look wise, knowing, and timeless. They escape the close-fitting comfort of a single meaning, forever inviting readers and viewers to try to fill in the gaps. Aurangzaib Khan, in his modest, exciting series of black and white photographs, summons long-dead potters, their creations, the little homes in the little villages they must have adorned, the husbands and wives and children who would eat and drink from them. He summons a past both local and grand, taking everything he needs from just one archaeological dig under the stars.

Dua Abbas Rizvi is a visual artist and writer