“Much have I travelled in the realms of gold,

And many goodly states and kingdoms seen;

Round many western islands have I been

Which bards in fealty to Apollo hold ...”

In writing these lines in his sonnet “On First Looking into Chapman’s Homer” the English romantic poet John Keats was referring in general to the wonderful poetry he had read, and in particular to the inspiration he received on reading Chapman’s translation of the ancient Greek poet Homer’s epic poem Odysseus. We shared a similar journey of exploration, of heart and soul and intellect, with the renowned architect and avid collector Habib Fida Ali, whose outstanding colonial art exhibition, “Journey of Passion,” amazed viewers at Chawkandi Gallery in Karachi. He himself lives in a beautiful colonial style house. His vast collection, he says, is born of his lifelong passion for Mughal and colonial history, though he says that actually the first piece he ever bought was in the 1960s, from the Gandhara civilisation. He inherited the collector’s gene from his father, whose huge stamp and coin collection took up shelf after shelf in his childhood home. However, what we saw - chosen by Habib himself along with Chawkandi’s founder, Zohra Husain and curator Niloufur Farrukh - was only a fraction of his collection, gathered from “... many goodly states and kingdoms ...”, principally from the South Asian subcontinent.

Altogether his recent exhibition comprised mostly drawings, paintings, old photographs, reproductions, ivory miniatures, inlay art and metalwork in brass, bidri and silver, and it is interesting to learn how and where these pieces were found. His youth, spent in London while studying architecture at the Architectural Association, enabled him to frequent antique markets from Portobello Road to Bermondsey in London’s East End. His face, his passion for discovery and his good taste were well known by shopkeepers there, who would call him to examine newly arrived, exquisite pieces. So just as Keats and a friend spent all night poring over Chapman’s translation, the young Habib was frequently to be seen at 5 a.m., examining prize pieces in these places by torchlight. Similarly Mumbai, Dhaka and Bangkok offered irresistible treasures, as did the Old Disposal House and other such establishments in Karachi’s Nursery area, from where he enriched his treasure trove with antique furniture, doors, carpets, furniture and so on. Meanwhile, his recent exhibition comprised mostly dra4wings, paintings, old photographs, pietra dura pieces, reproductions, ivory miniatures, inlay art and metalwork in brass, bidri and silver.

A young Habib could often be seen at 5 a.m., examining prize art-pieces by torchlight

Whereas he travelled far and wide, so to speak, as Aladdin was forced to do to find his desired riches, we viewers had only to take a lift up to the first floor and open Chawkandi Gallery’s door - without the use of any magical passwords - to be rewarded with the sight of a remarkable “cave” full of treasures. And whatever plans one may have had for methodical or even selective viewing went by the board, because from the first exhibits - a miniature, a photograph and a watercolour of the Hiran Minar at Sheikhupura on the outskirts of Lahore - one was captivated. Previously the jungles surrounding this monument were used as a royal hunting ground, but on the death of Mughal emperor Jahangir’s beloved deer Mans Raj, the area was declared a wildlife sanctuary. Of course, to appreciate fully this silently majestic, well-maintained monument - reflected in an artificial lake and commissioned by Jahangir in 1607 - one must go there alone on a misty, quiet morning. One must traverse every inch of the place on foot, and perhaps even spend 3 hours photographing it. The aforementioned photograph could be said to break a cardinal rule of photography, namely that the subject must not be placed dead centre, but since this composition is symmetrical, perhaps this summation does not stand.

The piece de resistance is the shining silver plaque showing a hunting scene from Gujrat or Rajasthan

The ivory miniatures displayed nearby were a later development of the paintings of famous monuments, (above all the Taj Mahal and Humayun’s Tomb), mosques, including the Badshahi Mosque, the Moti Masjid at Agra, the Panch Mahal at Fatepur Sikri, and others. With the arrival of the British, such paintings were produced in set after set of watercolours for these new patrons - like the postcards now produced en masse for modern tourists. In about 1830 came the ivory miniatures, portraying the same types of subject, but with a softer and more mellow treatment. Common productions were sets of Mughal emperors and their court beauties, rendered on ivory in oval frames. Here, the piece de resistance is a large miniature depicting various Mughal monuments, forts, the Taj Mahal , and similar subjects, with kings and queens of that period. The centerpiece is the Diwan i Khas of the Red Fort in Delhi, and this also appears in great detail in a separate miniature, where its impressive spaces and beauty of style - liberally embellished with pietra dura - make it hard for the viewer to move on through the rich display.

Many exhibits are reproduced from The Illustrated London News (ILS in journalists’ parlance), which was the world’s first illustrated weekly news magazine, founded by Herbert Ingram. It was a forerunner in the use of various graphic arts, being in fact the first to make extensive use of woodcuts, engravings and photographs, while its approval by the Archbishop of Canterbury ensured it the support of much of the public. And what a treat it was to see among Habib’s ILS engravings a view of our beloved Murree in its early, wonderfully un-spoilt days, and to identify familiar landmarks such as the church which still graces the Mall road, and the road winding up to Kashmir Point. Then there is a detailed and seemingly faithful print of Attock Fort. Though lacking modern techniques of reproduction, these and other such prints are a little dull. It must be noted, of course, the artists excelled themselves in depicting the royal tour of India in 1875, with huge, eminently clear and dramatic engravings of the arrival of the Prince of Wales in Lahore, Agra and other famous cities. The Agra piece is amazing in its depiction of architectural features in the background, the beautifully caparisoned elephants, the oriental symbols of royalty surrounding the prince and other visiting dignitaries. Here one can see the various court officials and of course, His Royal Highness, elegantly acknowledging the multitudes who had turned out to welcome him.

Seeing the watercolours and the old photograph of the Taj Mahal in Agra, one hears again the opening words of Wordsworth, in his wonderful sonnet, “Composed upon Westminster Bridge”:

“ Earth hath not anything to show more fair.

Dull would he be of soul who could pass by

A sight to touching in its majesty ...”

Daniel’s “Taj Mahal View from the Garden” is a pleasantly stylised composition with an appealing softness about it, though his inclusion of so much in the foreground makes it appear somewhat crowded. On the other hand, his “Taj Mahal View Across the River” is more spacious, as well as being unusual in its inclusion of details such as the elephant and camel, the boats, a few river folk, the reflection of this historic building in the river and the beautiful, broad expanse of cloudy sky above - and other details of the monument’s natural surroundings. But Wordsworth’s description, in the abovementioned sonnet, of London as being “All bright and glittering in the morning air” brings pangs of regret, a touch of irony, when we consider the air pollution that now exists - and is resulting in the de-colouring of the formerly pristine white marble of this beautiful edifice, as did the now forbidden habit of burning kachra (trash) far too close to it.

Along with Daniel, who was in India for 10 years, Flemish artist Balthaar Solvyns, who lived in Calcutta from 1791 to 1803, was one of the early print makers in India, and showed by this means the European image of India at that time. Habib displayed a fair number of his works, and though Solvyns is little known, his rather formal portraits of Bengali people in various occupations, at festivals and so on are indeed a rare find, though the book now being prepared for publication will make his work known to the public.

Seeing the historic buildings depicted among the prints and old photographs, such as Akbar’s tomb and Itimadud-Daula in Agra, Humayun’s Tomb and the Jamia Masjid in Delhi, one wishes they could see the original edifices face to face. Shown as they are in the nostalgic sepia tones of yesteryear, regardless of the skill of the photographers, a certain richness is missing, though this is not because of the sepia tones. And the habit of taking such photographs with the subjects dead-centre was apparently common.

There are also pangs of regret when one considers the state of ruin and dilapidation which haunts so many ancient architectural treasures in India and Pakistan today. Restoration is being carried out here and there but progress is slow, due in Pakistan, at least, to lengthy court proceedings, paucity of funds and centuries of simple neglect.

There are three exhibits devoted to Lahore’s Masjid Wazir Khan, a mosque built in 1635 to enclose the tomb of Sufi saint Miran Badshah, and replaced the Mosque of Mariyam Zamani Begum as the city’s Jamia Masjid. How fortunate viewers were to see this place of worship as it was then, with its beauty of line and the reverence with which it was constructed clearly visible from the wide expanse of its approaches, and with the inevitable hawks even then circling above. Years ago (in the 1990s to be precise), one approached it via a narrow gully, squeezed in as it was amongst so many shops and vendors, which quite robbed it of its formerly grand first appearance. The view of the inner courtyard is also impressive, crowned as it is with decorative masonry, featuring below this such traditional embellishments as pietra dura, while the interior features lovely mosaic and fresco work, as well as kasha kari tiles imported from Kasha in Persia. It is interesting to compare these features with Habib’s treasured views of the interior of Agra’s Chini Rouza Mau.

In the midst of all this is a fascinating conglomeration of works in brass, bidri and silver, including huqqa bases in brass and bidri, brass ewers, bidri vases, silver khasdan, gulabpash, brass and silver flower vases, and even a set of silver chains formerly supporting a swing used by a princess. The exquisite, intricate and formal floral decorations on most of these pieces leave nothing to be desired. Mark Zebrowski once said, “Metal-work has always been to India what ceramics are to China (and Japan)...” and “Order, beauty, richness, restraint and sensuousness describe the essence of these works of art, whose greatness derives from the meeting of two worlds. Such mingling of Hindu and Muslim sensibilities gave Mughal art the strength to endure, just as religious tolerance gave political strength to the Mughal emperors.”

Perhaps bidri is less familiar to many of us than brass and silver engraving, though its artisans share the same patience and love of creation The hometown of bidri is Bidar in India’s Karnataka state, and it is believed to have entered India over 4,000 years ago via the culture-rich Persians and Syrians. Today, the base metal is an alloy of zinc and copper. The designs are traced by hand with chisels, pure silver wire is laid in the grooves to form the designs and finally oil is rubbed on the piece to deepen the black matt coating.

But among all the lovely metal exhibits, the most arresting, the piece de resistance, is definitely the shining silver plaque showing a hunting scene from Gujrat or Rajasthan. One huntsman sits on a platform in the treetops, while others appear to be on foot amongst the rich and varied vegetation, while the dogs race around hoping to catch the scent of the big cats. And we can see a type of barrier, which is shifted gradually inwards to allow the hunting party to move closer to their prey. It is an example of exquisite craftsmanship, reminiscent of a scene from a fairytale, with its own double frame, also in silver. It also represents a time before conservation measures were necessary to protect endangered species. There are now only 2,000 tigers in India. How many were there in those days? One wonders.

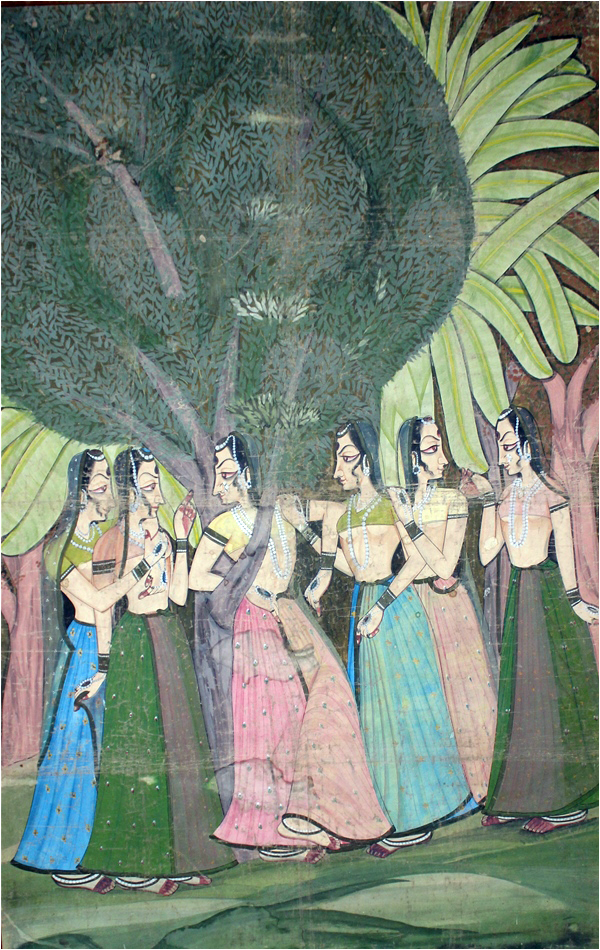

One of a kind (and therefore impossible to ignore) was the noted Aziz Mirza’s copy of a pichwai (Sanskrit pich - ‘back’- and wai – ‘to hang’) from a Hindu temple. Rooted in Rajasthan, these are created and used as backdrops in the Shrinathji Temple in Nathdawara, and in other Krishna temples, the main theme being Shrinathji and his exploits. Generally they are executed in dark hues on rough, handspun cloth. This is so in the example included in this exhibition, where the contrast of light and dark and the grace of the whole composition give it a pronounced charm.

As an outstanding architect, as a collector and as the one who restored the Mohatta Palace as his “gift to Karachi,” Habib Fida Ali has certainly earned a place in posterity. This will be greatly enhanced if he realises his dream of building a museum around his vast collection, if a piece of land is made available by the state. The museum itself, the collection and the cost of building the museum would be another handsome gift to Karachi from this great man, and would no doubt draw visitors from far and wide. To quote from “All’s Well that Ends Well” one of Shakespeare’s gifts to mankind, “Whate’er the course, the end is the renown.”