In present-day Pakistan, where student unions have been banned since 1983, it is important to make the distinction between student unions and student wings of political parties. Educational institutions are supposed to provide office space for student unions - elected, representative bodies focused on student-related issues, social activities and academic support. Student unions are the nursery of politics even as they cut across party politics.

In 1953, Karachi, although highly cosmopolitan, lacked the educational infrastructure to cater to its rapidly increasing population as migrants flooded to the capital in those post-Partition years. Its colleges, affiliated with Bombay University until now, were mostly public funded and catered to the middle and lower middle-class. Dow Medical College, the nerve centre of DSF’s activities, was still struggling to get its degree recognised. It also lacked staff and equipment.

My father reserved his anger for larger issues, shrugging off minor irritants like bad traffic or annoying people

The co-mingling of a diverse population in Karachi’s colleges “produced a synergy which propelled the demand for democratic reforms in the educational system which was at the core of the DSF’s agenda,” says S. M. Naseem, the well-known Marxist economist and newspaper columnist (‘Sarwar, DSF and the ‘Students’ Herald’, 2009 https://drsarwar.wordpress.com/2009/08/11/sarwar-dsf-and-the-students-herald-s-m-naseem/).

As DSF gained ground in Karachi’s college unions, Vice-President of the Dow Medical College Union Mohammad Sarwar “devised the master-stroke of forming an Inter-Collegiate Body (ICB) of all the College Unions. In the interest of the broad-based unity of the student community, he decided to get elected a non-DSF Vice-President of a College Union as ICB Chairman instead of keeping the post himself,” writes Naseem, who established the DSF Unit in S. M. College.

The ICB deliberated over the issues that students faced, and formulated a list of demands for the Education Minister Fazlur Rehman. His refusal to meet them led to their decision to observe a Demands Day on 7 January 1953. “The rest, as they say, became history, demonstrating Sarwar’s skills as a consummate strategist.”

Sarwar, a lanky six-footer with large, intense eyes, and thick, wavy hair slicked back in the fashion of those times towered over most of his comrades.

The somewhat remote, calm and quietly confident father of my childhood reserved his anger for larger issues, shrugging off minor irritants like bad traffic or annoying people. As I grew up, he became my political guru - as he was for so many. He spoke sparingly, the words punctuated by thoughtful pauses, occasional glimpses of sardonic wit breaking through the serious demeanour. It was only after retiring from the small Nazimabad clinic where he was a family doctor for generations of patients - often treating the needy for free - that he would talk about the past when prodded.

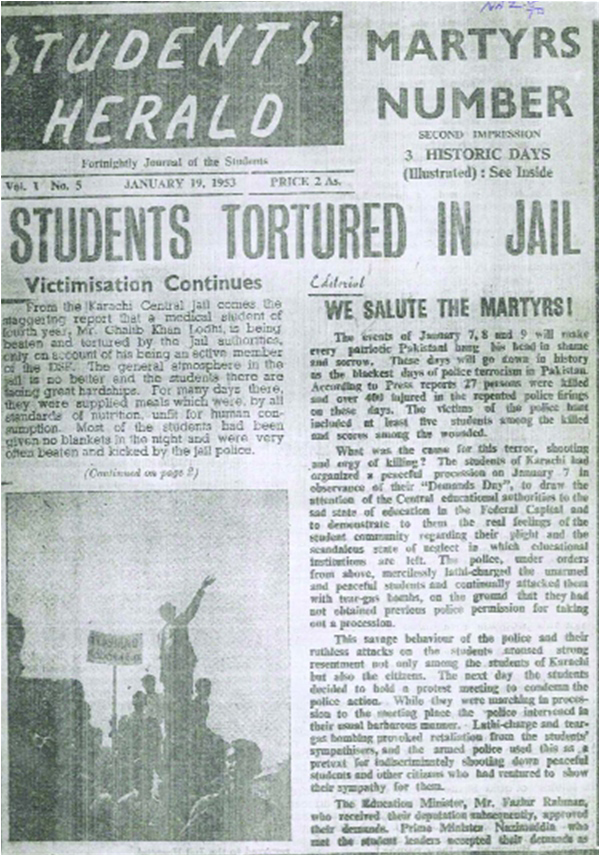

The administration’s heavy-handed response to the students’ peaceful protest catapulted the movement to centre stage. Police firing between January 7 and 9, 1953, killed 27 people. The Students’ Herald issue titled ‘Martyrs Number’ of January 19, 1953, lists the names of eight students and 15 non-students killed, besides some 400 injured and arrested. Official figures were 10 killed and 80 injured.

I learn more about the DSF story from memories shared by my father, interviews conducted for my documentary, Aur Niklenge Ushhaq ke Qafley (online at: https://vimeo.com/beenasarwar/ushhaq), and not least, the Students’ Herald, ‘Fortnightly Journal of the Students’, published from January 1953 to July 1954.

The story of the Students’ Herald itself is fascinating. It began when S. M. Naseem obtained a declaration for the Herald in his individual capacity, the application cleared by a CID officer unsuspecting of his real intentions. These were to establish a journal that would mobilise students in favour of DSF’s objectives. DSF also felt an urgent need to counter the government’s propaganda against it in the national press and the student organ of the Jama’at–i-Islami, Students’ Voice, edited by Khurshid Ahmad (JI senator from 2003-2012).

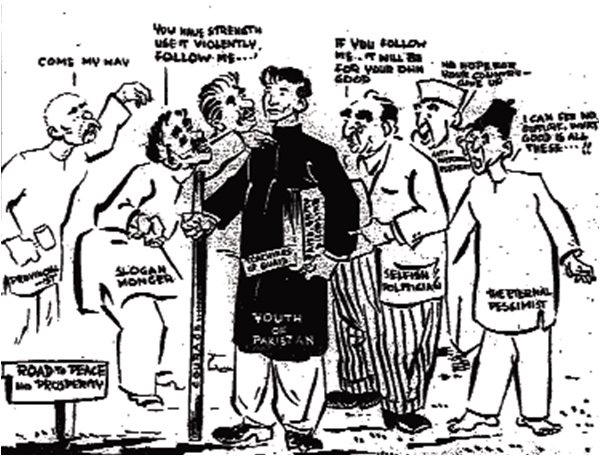

Naseem became the Students’ Herald editor, printer and publisher “largely by accident and default”. A fellow editor was Wasi Ahmad Hai “who left for Burma after his release from jail in 1954 and has never been heard from since”. Volunteer proof readers included Saleem Asmi, who culminated his journalistic career as Editor of the Dawn. The photographer was Sartaj Alam. Aziz, leading cartoonist of that time, contributed original cartoons.

Supportive journalists ghostwrote articles, helped edit the paper and provided guidance about layout and production. These included M. A. Shakoor, Eric Rahim, Ahmad Hasan and Sarwar’s elder brother, Mohammad Akhtar. All of them worked for the Dawn, and were later arrested and dismissed from their jobs. Supportive teachers like Prof. Samsamul Hai, Dr. A. H. Hamdani and Prof. M. Kareem also paid a price for their support.

The DSF's initial list of demands which they wanted to present to Education Minister Fazlur Rehman included:

- Reduce fees to the same level as those levied in Dacca and Lahore

- Construct new hostels

- Improve library and laboratory facilities

- Form a separate Ministry of Education

- Security of employment

The “editorial office moved from one Irani teashop to another”, shadowed by a CID inspector tasked with finding out the contents of the next issue. “He would often sit in the printing press and pressurise the owner to give him the proofs. But the owner, who was very helpful and allowed us to print the paper on credit and treated us to tea, refused to oblige,” says Naseem.

The entire operation required “a core group of dedicated and competent writers, proofreaders, advertisement-seekers and donation-collectors. Producing a paper was a much more labour-intensive and cumbersome job than in the electronic world of today”.

Those who helped fundraise for the publication included Mazhar Saeed, Zain Alavi and Ghalib Lodhi. “Sarwar himself often contributed articles to the paper and provided guidance on major issues.”

Students sold copies at street corners for two annas (an eighth of a rupee) each – which was “slightly more than the cost of a cup of tea in those days”. This was perhaps the only time in Pakistan’s history that a student publication was sold like this.

DSF tried to counter the government's propaganda in the national press and the student organ of the Jama'at-i-Islami

Advocate and literary critic Mazhar Jameel, then a high schooler in Sukkur, recalls carrying bundles of the paper and calling out to passers-by: ‘Students’ Herald, Students’ Herald, now on sale!’ Sukkur had the highest sales after Karachi, he added when interviewed for my documentary. But sales alone did not cover publishing costs and the students also raised donations.

As news of the police brutality of Jan 7, 1953 spread, students around Pakistan, including East Bengal, rose in solidarity with Karachi, bringing educational institutes to a standstill for the next two days, Thursday and Friday. Prominent activists in other cities included Abid Hasan Minto, Ayub Mirza, Ghalib Lodhi, Reza Kazim and Zuhair Naqvi, to name a few.

On Sunday, January 11, 1953, newspapers reported that college principals, in conjunction with the Karachi University Vice Chancellor, had decided to close all colleges and universities till January 17.

Prime Minister Nazimuddin asked to meet the student leaders at his residence in Karachi.

I wonder if education minister Fazlur Rehman had met DSF in the first place, would there have been a Demands Day, police firing or loss of lives?

The deputation of representatives of college unions and other prominent citizens that met with PM Nazimuddin and Interior Minister Gurmani on Saturday, January 10, 1953 included Mohammad Sarwar, Moiz Faruqi, Adeel Ahmed, Burney, and Jamal Naqvi among others.

The PM promised a judicial inquiry into the “whole affair”. He agreed to reduce the college fees in Karachi to the same level as Dacca and Lahore - one of DSF’s key demands - and to ensure that the money allocated for building hostels was speedily utilised. He also promised that “nobody would be victimised or persecuted on political grounds” (Dawn, January 11, 1953).

The students’ importance rose after their meeting with the Prime Minister. Leaving his house, my father would be offered rides in the chauffeur-driven cars of Muslim League leaders.

“We would refuse. We would walk or take a rickshaw,” said Sarwar with a dismissive wave of his hand, cigarette dangling between the forefingers. “Getting in one of those cars would be to sell myself and the cause we were fighting for.”

He remembered being asked to tea by Dawn’s powerful Editor, Altaf Hussain. He wanted DSF to take out a “victory procession” that he said should be led by the rising political star Yusuf Haroon. “It will be good for him and good for you.”

A scion of the family that owned Dawn, posted in Australia as Pakistan’s high commissioner, Haroon had returned to Karachi on January 10, 1953. A front-page news item on Dawn on January 11, 1953, reported his “enthusiastic welcome” at Keamari harbour.

Ironically, a front page cartoon in Dawn, Jan 11, 1953 shows various corrupting influences trying to influence the “Youth of Pakistan”.

The students, wanting to retain their independence, rejected Hussain’s suggestion. He was not pleased.

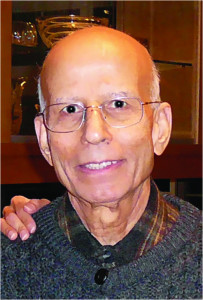

Obituary

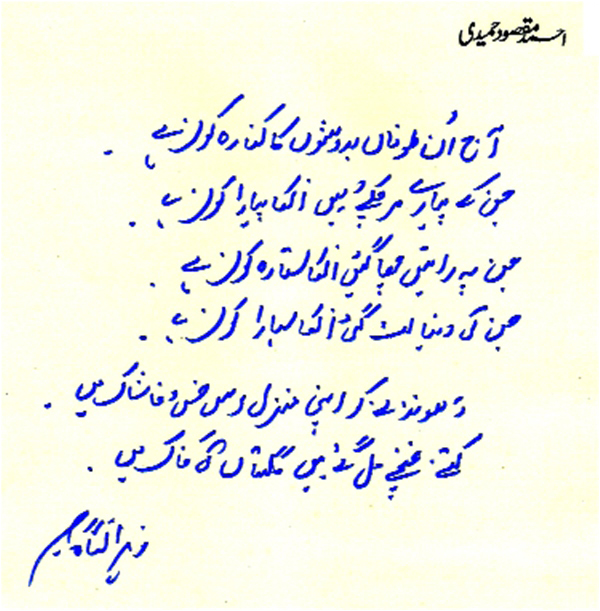

A founding member of the DSF, Dr Asif Ali Hameedi, passed away this week in Grand Rapids, MI, USA yesterday.

A founding member of the DSF, Dr Asif Ali Hameedi, passed away this week in Grand Rapids, MI, USA yesterday.

His wife passed away three years ago. They are survived by their three children, Samia Hameedi-Brown, Ashraf Hameedi and Jamal Hameedi.

"Very sorry to hear the sad news. I recall him as a serious scholar of Marxism -some called him "our Liu Shaoqi" - and a committed DSF activist, who shunned the limelight," recalled S. M. Naseem.

"It is indeed sad news. Asif Hameedi was one of the founders of DSF. There are now so few of us left to mourn the death of our dear comrade. We often talk about him when we take stock of the DSF members and feel depressed at the ever-shrinking number. May he be blessed and rest in peace," wrote Zain Alavi.

The writer is a journalist and documentary filmmaker – www.beenasarwar.com. She tweets @beenasarwar. This essay is an extract from her forthcoming memoir on the struggle for democratic spaces in Pakistan. The first part of this series was published in TFT on January 8, 2016