For the second consecutive year, Karachi saw a sharp decrease in homicidal violence in 2015. This drop was even more pronounced than the preceding year: according to Karachi Police’s statistics, the number of persons killed in the city went down from 2,789 in 2013 (the deadliest year, to date, in the history of Karachi) to 1,925 in 2014 and 986 in 2015.

For the second consecutive year, Karachi saw a sharp decrease in homicidal violence in 2015. This drop was even more pronounced than the preceding year: according to Karachi Police’s statistics, the number of persons killed in the city went down from 2,789 in 2013 (the deadliest year, to date, in the history of Karachi) to 1,925 in 2014 and 986 in 2015.This improvement of the so-called “law and order situation” is heavily indebted to the operation launched in September 2013 by the Nawaz Sharif government, which was intensified in 2015 at the behest of the army. In fact, the Karachi Police and the Rangers deserve to be credited for the decline of almost every category of crime in the city (to the exception of cell phone snatching) over the last two years.

Before celebrating the success of the Karachi Operation, however, one should remember that official data on yearly killings do not include “encounter deaths”, which registered a significant decline between 2014 and 2015 but which remained at a worrying level – with 703 alleged “criminals” killed by the Karachi Police and the Rangers last year, according to official figures, against 925 in 2014. Rather than a proper pacifying of Karachi, what an attentive reading of these official statistics indicates, instead, is the containment of one form of violence by another.

Performances of state violence tend to weaken democratic institutions

A state monopoly over violence

These recent evolutions confirm that law enforcement agencies, far from being passive spectators of Karachi’s conflicts, retain a capacity to control the rate of violence in the city. The improvement of the security situation came at a heavy price, though. Since the 1990s, the restoration of the “writ of the state” in Karachi seems to imply the suspension of the rule of law, the normalization of exception and the transfer of authority from elected representatives to the security apparatus. In the short run, these emergency measures might provide temporary relief to the city’s law-abiding citizens. But on the longer term, performances of state violence tend to weaken democratic institutions and to alienate significant sections of the population from the state claiming to represent and protect them. Moreover, there are concerns whether state authorities – which are always more inclined to clean the society than their own act – will lead this fight to its logical conclusion, that is, the restoration of a state monopoly over violence (which never really existed in the first place). In the past, every “clean up” operation was essentially an opportunity for civilian and/or military elites to establish new partnerships with private enforcers coercing the local population. So far, the army – which is now de facto leading the Karachi operation – has retained a safety distance from the militias and criminal gangs that it was suspected to have instrumentalized in the past. The military still has a long way to go to appear as an impartial arbiter of Karachi’s conflicts, however.

MQM and the challenges that lay ahead

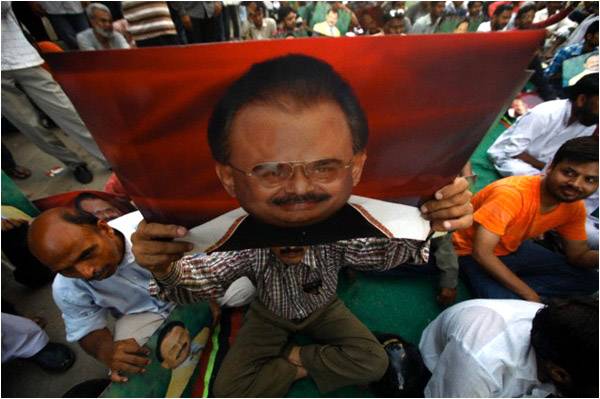

While there is an eerie sense of déjà vu in these performances of “legitimate” violence leading to a rise in extrajudicial killings, major political changes are in the air. One of the most sensitive and far-reaching issues for the future of Karachi will be the redistribution of authority within the MQM following the retirement of Altaf Hussain, be it forced or voluntary. The recent electoral victories of the party, from the by-election of April 2015 in NA-246 to the local government elections held last month, demonstrated without any ambiguity that the party retains a strong constituency in the city. But the future of the MQM will depend as much on outside sources of support and pressure as on internal arrangements of authority – between the exiled and the Pakistan-based leadership, as well as between grassroots leaders (the units- and sectors-in-charge) and the more polished party cadres gathered in the Coordination Committee. Altaf Hussain will not always be there to bridge these differences (which he is alleged to have fuelled to keep his hold over the party) and the battle for his succession promises to be a bitter one. Meanwhile, the party will be struggling to address rapidly and effectively its constituents’ everyday concerns. The capacity of the MQM leadership to restore confidence on this count will be hampered by the curtailed prerogatives of Karachi’s local government, courtesy of the PPP, but also by probable attempts on the part of the military to project the MQM as an impotent and increasingly irrelevant political force.

Karachi’s political economy in a state of flux

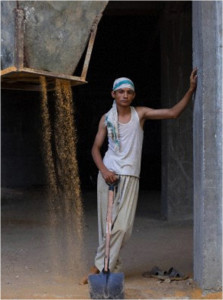

Recent transformations of Karachi’s political economy, in a context of persisting uncertainty and insecurity, have received much less attention so far but will also prove critical for the future of the city. While the wholesale markets and more generally the trading economy of Karachi’s Old City have been severely disrupted by criminal violence and extortion, other sectors of the economy have adjusted better to the city’s volatile environment. In recent years, the textile and pharmaceutical industries, in particular, have turned to political parties and criminal groups for various services. These extended from lower-cost illicit water connections to the control of the workforce, which was discouraged by local power holders and their musclemen to organize and mobilize itself for better wages and working conditions. This discouragement involves the recourse to both carrot and stick, as these local power holders do not only have coercive resources at their disposal but have also been invested with a power of recruitment (or readmission, in the case of workers dismissed arbitrarily). Even Jihadi and sectarian organizations have taken a foothold in some factories. In 2013, the management of a notorious pharmaceutical company based in SITE called upon militants of the Jamaatud Dawa after some workers tried to set up a union. The same year, the Karachi chapter of Ahle Sunnat Wal Jamaat (ASWJ) set up a Labor Committee, which has been mainly active in Landhi/Quaidabad. By funding their madrasas via zakat, factory owners have also tried to coopt preeminent clerics so as to obtain fatwas against strikes. At the same time, industrialists recruited former army officers who helped them beef up their security, which sometimes extends well beyond the walls of factories themselves through a network of CCTV cameras scattered across industrial zones and labor colonies.

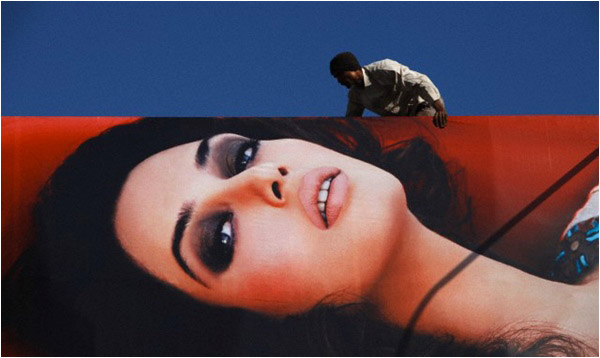

From the disorderly environment that characterizes Karachi’s politics and its economy seems to have emerged a new brand of capitalism: highly extraverted (these are all export-oriented industries), utterly disrespectful of workers’ rights and increasingly coercive. While coercion was integral to the development of Karachi’s industrial sector in the 1960s and early 1970s, it used to be primarily the business of the state. But as security is being privatized, coercive capacities are being transferred to corporate actors. The state hasn’t entirely disappeared from the picture. On several occasions, the Rangers also lent a hand to industrialists trying to dissuade workers from organizing themselves.

Here as elsewhere in Karachi, the retreat of the state is an optical illusion. State agencies and their personnel – the military, the police, the judiciary, the provincial Board of Revenue etc – remain essential to the political and economic regulation of the city, including in the informal sector. However contested and intermittently exercised state authority may be, public actors retain a power of arbitrage and mediation in all walks of life. If some corporate actors, especially in the textile industry and the real estate sector, are becoming major protagonists of Karachi’s ordered disorder, their rising clout remains tributary to the goodwill of state regulators. Accumulation by dispossession does not operate beyond the ambit of state power. Corporate actors use the law, the police and other forms of state protection to grab land, exploit labor and crush every resistance with impunity. This impunity remains relative, however, as state patronage can never be taken for granted in the long run.

Laurent Gayer is senior research fellow at the Center for International Studies and Research (CERI)/Sciences Po, Paris. He recently published Karachi: Ordered Disorder and the Struggle for the City, available in South Asia through HarperCollins India