Here we are in the middle of the Labor Day doldrums. In meteorological terms, doldrums are those areas of the globe and times of the year when there is no wind. In the days of sailing ships it was a time to be feared, and a time to avoid the tropical latitudes. During the doldrums, the warm, tropical air rises and thus the wind ceases to blow. The danger that springs from such doldrums in modern times is that the rising warm air forms into tropical storms, which sometimes become hurricanes, which occasionally wreak havoc when and if they hit land. So the meteorological doldrums have not lost their punch yet.

But I think there is a political meaning to Labor Day Doldrums also. It is a time of unmitigated boredom, normally the early days of September, when the weather is still hot, the kids are not yet in school, and the politics of either the Congressional off- year election or the Presidential election are sending additional drafts of hot air skyward. Labor Day is by law the first Monday in September, and this year it is late. This additional time has led to an expanded amount of hot air rising from the political rhetoric around the country to increase temperatures by a few degrees, and certainly has increased the tempers of our many political aspirants even more.

In the past, Labor Day has been traditionally, in Presidential election years, the official kickoff of the election campaigns of the major parties. Major campaigning went on for three months, which seems like a reasonable period of time for an election campaign in a large and populous country like the US. But that is a relic of the past. With the advent of primaries and worse – the unlimited political funding of campaigns permitted by the Supreme Court’s decision in Citizens United v FEC decision of 2010. Unless the Supreme Court decision can be overturned, I fully expect campaigning will soon begin on the Labor Day after the Presidential election and to go on for three years. And the proliferation of money will attract so many candidates that they won’t all fit on the same stage to debate (the Republican Primary this year has 18 candidates.)

So what can I write about as we pass through the Labor Day doldrums? In Pakistan, the counterattack on the PML-N government – and indirectly on the Army – by Asif Ali Zardari and the PPP is being explained by my friends in the Pakistani press much better than I could. In Bangladesh, it is déjà vu all over again—a continued squeezing of the opposition, holding out the tempting prospect of talks with the opposition while destroying it, and the continued drift to a one-party authoritarian state. Nothing new to write about in either case. Should I write about the American politics that is producing all that hot air—about Hilary Clinton’s incredible faux pas with the emails and the personal server, or about Donald Trump’s bombastic nativist trumpetings on (illegal) immigrants which are reminiscent of Andrew Jackson’s marching the Cherokee and other Southeastern tribes from Georgia to Oklahoma along the “Trail of Tears.” No I can’t write about that; it would appear as tragic farce to most TFT readers.

While reflecting on this quandary over breakfast this morning, I opened an edition of the New York Review of Books I had been saving and came across something new – a book and art exhibit review by William Dalrymple, one of my favorite writers on South Asian history. And there it was: the answer to my quandary. In a review of a book and an exhibition, Dalrymple described one of the greatest, if not the greatest, flowering of art in Muslim India, in 17th Century Deccan. I hope Mr Dalrymple will not be too upset if I borrow facts from his article to make several points that should resonate in our own time.

As we all know, the Mughals swept into India in the 16th century and by the early 17th controlled most of North India leaving the fragmented Sultanates of the Deccan plateau to fend for themselves. These dynamic and culturally and aesthetically independent states thrived, and they fostered an intellectual and artistic flowering which may have no equal in Indian history. The Sultanate of Bijapur and its ruler Ibraham Adil Shah led this revolution. He invited to his court many of the best painters and poets of his day from throughout the world he knew, Persia, Turkey, Central Asia, Abyssinia, and as far away as Holland. This wide collection of artists and intellectuals established a cultural renaissance that spread to the other Deccan Sultanates, Bidar, Ahmadnagar, and Golconda. The region produced an enormous quantity of outstanding art, music, and poetry that is only now becoming recognized by art historians for its quality and uniqueness. The results of that flowering have been on display at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art and have been hailed as significant art that had not received the recognition it deserves.

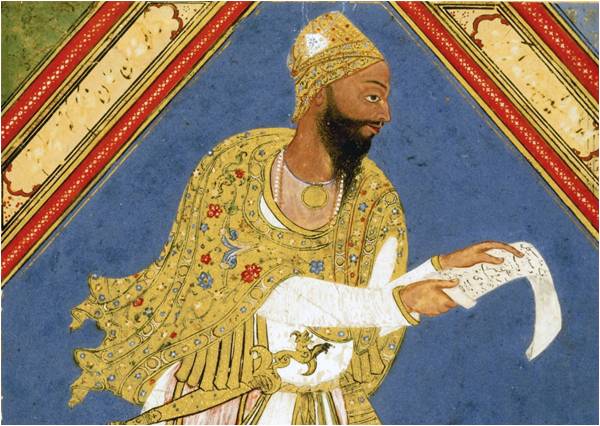

According to Dalrymple, 17th Century Deccan courts were the most cosmopolitan in South Asia, in part because they had attracted artists and intellectuals from Turkish Central Asia who had “grown up during the flowering of the Persian Renaissance” who brought their cosmopolitan mindsets with them. Could such a culture live on the same subcontinent with the aggressive Mughals? One ominous comparison between contemporaries: Sultan Ibrahim Adil Shah, the romantic and dreamer who fostered the great artistic flowering of Bijapur, is typically depicted pictorially as either sleeping, or being fanned by his servants; the great Mughal Emperor Akbar, an illiterate but brilliant military leader is usually depicted leading his army or storming a fort.

The Deccan in this period was also a place that brought together strands of thought in ways that by today’s standards would verge on being denounced as heretical or apostate. Bijapur was a major center of unorthodox Sufi thought, and in music particularly very open to Hindu influences.

Of course, all this was too good to survive in the real world of aggressive and grasping empires. As Dalrymple notes, “a Kingdom so obsessed with the arts could only be hopelessly vulnerable to more worldly and militaristic forces.” It turns out that Sultan Ibrahim had been buying off the Mughals for most of the years of his reign – with jewels, his daughter, his favorite elephant, and much money – and finally running out of things he could give the Mughals. In 1686, the puritanical Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb, outraged by Bijapur’s syncretic, open culture, put an end to the artistic flowering of the Deccan.

Somehow, this historical episode reminds me of something I once wrote about Shakespeare’s Marc Antony. He fell in love with the sultry queen of the Nile, Cleopatra, who like the Nile itself, was life-giving, simple and optimistic – immune from all bad news. She came to represent all that he had come to desire. But he knew the Legions were coming, and he accepted a short idyllic life with his exotic Queen rather than a life driven by the illusion that he could make things better by waging war. Does it seem to you, as it does to me, that Ibriham Adil Shah chose his life of art, music and poetry, and to keep it going for as long as possible by bribing the Mughals? But in the end, the Legions—or in this case the Mughals—arrived. The bad guys always do.

The author is a Senior Scholar at the Woodrow Wilson Center in Washington DC and a former US diplomat who was Ambassador to Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Chief of Mission in Liberia

But I think there is a political meaning to Labor Day Doldrums also. It is a time of unmitigated boredom, normally the early days of September, when the weather is still hot, the kids are not yet in school, and the politics of either the Congressional off- year election or the Presidential election are sending additional drafts of hot air skyward. Labor Day is by law the first Monday in September, and this year it is late. This additional time has led to an expanded amount of hot air rising from the political rhetoric around the country to increase temperatures by a few degrees, and certainly has increased the tempers of our many political aspirants even more.

In the past, Labor Day has been traditionally, in Presidential election years, the official kickoff of the election campaigns of the major parties. Major campaigning went on for three months, which seems like a reasonable period of time for an election campaign in a large and populous country like the US. But that is a relic of the past. With the advent of primaries and worse – the unlimited political funding of campaigns permitted by the Supreme Court’s decision in Citizens United v FEC decision of 2010. Unless the Supreme Court decision can be overturned, I fully expect campaigning will soon begin on the Labor Day after the Presidential election and to go on for three years. And the proliferation of money will attract so many candidates that they won’t all fit on the same stage to debate (the Republican Primary this year has 18 candidates.)

He knew the Legions were coming, and he chose a short idyllic life with his exotic Queen

So what can I write about as we pass through the Labor Day doldrums? In Pakistan, the counterattack on the PML-N government – and indirectly on the Army – by Asif Ali Zardari and the PPP is being explained by my friends in the Pakistani press much better than I could. In Bangladesh, it is déjà vu all over again—a continued squeezing of the opposition, holding out the tempting prospect of talks with the opposition while destroying it, and the continued drift to a one-party authoritarian state. Nothing new to write about in either case. Should I write about the American politics that is producing all that hot air—about Hilary Clinton’s incredible faux pas with the emails and the personal server, or about Donald Trump’s bombastic nativist trumpetings on (illegal) immigrants which are reminiscent of Andrew Jackson’s marching the Cherokee and other Southeastern tribes from Georgia to Oklahoma along the “Trail of Tears.” No I can’t write about that; it would appear as tragic farce to most TFT readers.

While reflecting on this quandary over breakfast this morning, I opened an edition of the New York Review of Books I had been saving and came across something new – a book and art exhibit review by William Dalrymple, one of my favorite writers on South Asian history. And there it was: the answer to my quandary. In a review of a book and an exhibition, Dalrymple described one of the greatest, if not the greatest, flowering of art in Muslim India, in 17th Century Deccan. I hope Mr Dalrymple will not be too upset if I borrow facts from his article to make several points that should resonate in our own time.

As we all know, the Mughals swept into India in the 16th century and by the early 17th controlled most of North India leaving the fragmented Sultanates of the Deccan plateau to fend for themselves. These dynamic and culturally and aesthetically independent states thrived, and they fostered an intellectual and artistic flowering which may have no equal in Indian history. The Sultanate of Bijapur and its ruler Ibraham Adil Shah led this revolution. He invited to his court many of the best painters and poets of his day from throughout the world he knew, Persia, Turkey, Central Asia, Abyssinia, and as far away as Holland. This wide collection of artists and intellectuals established a cultural renaissance that spread to the other Deccan Sultanates, Bidar, Ahmadnagar, and Golconda. The region produced an enormous quantity of outstanding art, music, and poetry that is only now becoming recognized by art historians for its quality and uniqueness. The results of that flowering have been on display at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art and have been hailed as significant art that had not received the recognition it deserves.

According to Dalrymple, 17th Century Deccan courts were the most cosmopolitan in South Asia, in part because they had attracted artists and intellectuals from Turkish Central Asia who had “grown up during the flowering of the Persian Renaissance” who brought their cosmopolitan mindsets with them. Could such a culture live on the same subcontinent with the aggressive Mughals? One ominous comparison between contemporaries: Sultan Ibrahim Adil Shah, the romantic and dreamer who fostered the great artistic flowering of Bijapur, is typically depicted pictorially as either sleeping, or being fanned by his servants; the great Mughal Emperor Akbar, an illiterate but brilliant military leader is usually depicted leading his army or storming a fort.

The Deccan in this period was also a place that brought together strands of thought in ways that by today’s standards would verge on being denounced as heretical or apostate. Bijapur was a major center of unorthodox Sufi thought, and in music particularly very open to Hindu influences.

Of course, all this was too good to survive in the real world of aggressive and grasping empires. As Dalrymple notes, “a Kingdom so obsessed with the arts could only be hopelessly vulnerable to more worldly and militaristic forces.” It turns out that Sultan Ibrahim had been buying off the Mughals for most of the years of his reign – with jewels, his daughter, his favorite elephant, and much money – and finally running out of things he could give the Mughals. In 1686, the puritanical Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb, outraged by Bijapur’s syncretic, open culture, put an end to the artistic flowering of the Deccan.

Somehow, this historical episode reminds me of something I once wrote about Shakespeare’s Marc Antony. He fell in love with the sultry queen of the Nile, Cleopatra, who like the Nile itself, was life-giving, simple and optimistic – immune from all bad news. She came to represent all that he had come to desire. But he knew the Legions were coming, and he accepted a short idyllic life with his exotic Queen rather than a life driven by the illusion that he could make things better by waging war. Does it seem to you, as it does to me, that Ibriham Adil Shah chose his life of art, music and poetry, and to keep it going for as long as possible by bribing the Mughals? But in the end, the Legions—or in this case the Mughals—arrived. The bad guys always do.

The author is a Senior Scholar at the Woodrow Wilson Center in Washington DC and a former US diplomat who was Ambassador to Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Chief of Mission in Liberia