It has been eight months since the enactment of the National Action Plan (NAP) against terrorism and extremism. Its various action items have seen varied progress, but one has remained particularly troublesome – the tenth point in the NAP that deals specifically with seminaries.

As pressure from a variety of sources mounted, the state showed some change in its approach towards the regularization and reform of seminaries in August, but the progress is limited, and if history is any indication, it will remain so.

Pakistan had 300 seminaries in 1947. The number had increased to 3,000 by 1988. Today, there are between 36,000 and 41,000 seminaries in the country. The figure includes roughly 26,000 registered seminaries, and an estimated 10,000 to 15,000 unregistered ones.

Until the 1990s, seminaries were registered under the Societies Registration Act of 1860, as charities. This requirement for registration was removed in 1996. The Benazir Bhutto government wanted to bring about comprehensive reforms in the sector, but failed.

In 2001, the Pervez Musharraf regime drafted the Madrassa Board Ordinance – an attempt to modernize seminary education through a range of measures. But only 449 seminaries – 1.8 percent of the total – were registered. The draft Voluntary Registration of Regulations Ordinance of 2002 was not signed by the president. In 2004, another attempt was made to modernize seminaries with the Government Madrassa Reforms Program, by changing their curriculum to include secular subjects. The program did not succeed.

The Societies Registration (Amendment) Ordinance of 2005 requires seminaries to submit annual reports of activities, funding and budget details to the registrar, mandates registration, and bans proliferation of hate. The amendment faced near universal disdain from the religious right, with the Ittehad Tanzeemat Madaris Pakistan (ITMP) leading the charge.

Nearly five months after the NAP was promulgated, there have been two key developments, both involving federal ministers. First, Federal Minister for Religious Affairs Sardar Muhammad Yousaf revealed early work on the formation of an Islamic Education Commission (IEC) to regulate seminaries across the country. There has been no tangible progress on that front so far. Second, Federal Information Minister Pervaiz Rashid had to swallow his pride and apologize publicly for calling seminaries centers of ignorance and illiteracy. He clarified that he was referring to the handful of them involved in hate speech and illegal activities, but the backlash was powerful enough to make him reel.

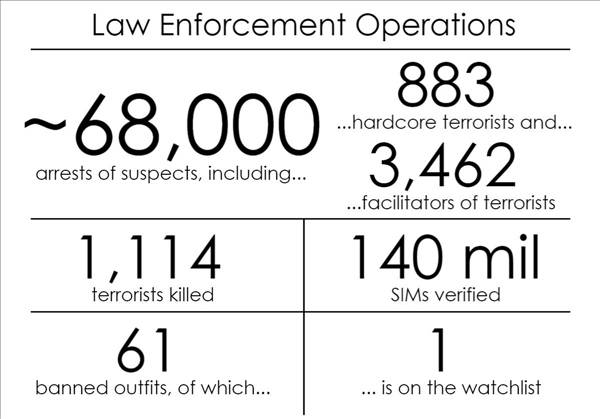

On July 29, Lashkar-e-Jhangvi leader Malik Ishaq and several of his companions were killed in a gunfight with the police in Muzzafargarh city in southern Punjab. Less than three weeks later, Punjab Home Minister Col (r) Shuja Khanzada and 22 others were killed in a suicide attack at his home in Shadikhan. These two incidents, especially the latter, began a chain of events in August that ended in law-enforcement action against seminaries across the country.

On August 3, Sindh Police chief Ghulam Haider Jamali told his men to compile a list of registered and unregistered seminaries in the province in 15 days. On August 6 and 7, Punjab police carried out search operations in seminaries in Lahore, Multan, Faisalabad, Gujranwala and Bahawalpur. In the capital territory of Islamabad, Inspector General Tahir Alam Khan vowed to monitor traffic coming in and out of the 329 seminaries in the city. On August 26, it was reported that 703 unregistered seminaries and mosque schools in the tribal belt were soon to be blacklisted – the first major step towards the goal of regulation of seminaries. In KP, under Inspector General Nasir Durrani, police has taken action against 1,250 violations of the loudspeaker act and hate speech.

But in a controversial statement on August 26, Punjab Law Minister Rana Sanaullah said no seminaries in Punjab had any links with extremism.

Earlier, on August 7, the Pakistan Ulema Council issued a code of conduct for new admissions in seminaries, suggesting a softening stance towards regulation. The code includes provisions for maintaining accurate records, rejecting foreigners without credentials, extra-curricular activities, security precautions, an enhanced curriculum to include conventional education, rules for loudspeaker use, and discouraging sectarianism and other forms of hate speech.

Historically, the registration of seminaries has been a contentious subject. The political will to deal with the issue may have existed, but the ground realities, such as fierce opposition from the right, have compelled various governments to backtrack. That finally seems to be changing. It remains to be seen if this momentum will continue.

The author is a journalist and serves as a Senior Research Fellow at the Center for Research and Security Studies, Islamabad. He holds a Master’s degree in strategic communications from Ithaca College, NY.

Email: zeeshan[dot]salahuddin[at]gmail.com

Twitter: @zeesalahuddin

As pressure from a variety of sources mounted, the state showed some change in its approach towards the regularization and reform of seminaries in August, but the progress is limited, and if history is any indication, it will remain so.

Pakistan had 300 seminaries in 1947. The number had increased to 3,000 by 1988. Today, there are between 36,000 and 41,000 seminaries in the country. The figure includes roughly 26,000 registered seminaries, and an estimated 10,000 to 15,000 unregistered ones.

Until the 1990s, seminaries were registered under the Societies Registration Act of 1860, as charities. This requirement for registration was removed in 1996. The Benazir Bhutto government wanted to bring about comprehensive reforms in the sector, but failed.

In 2001, the Pervez Musharraf regime drafted the Madrassa Board Ordinance – an attempt to modernize seminary education through a range of measures. But only 449 seminaries – 1.8 percent of the total – were registered. The draft Voluntary Registration of Regulations Ordinance of 2002 was not signed by the president. In 2004, another attempt was made to modernize seminaries with the Government Madrassa Reforms Program, by changing their curriculum to include secular subjects. The program did not succeed.

The Societies Registration (Amendment) Ordinance of 2005 requires seminaries to submit annual reports of activities, funding and budget details to the registrar, mandates registration, and bans proliferation of hate. The amendment faced near universal disdain from the religious right, with the Ittehad Tanzeemat Madaris Pakistan (ITMP) leading the charge.

703 unregistered seminaries in the tribal areas will be blacklisted

Nearly five months after the NAP was promulgated, there have been two key developments, both involving federal ministers. First, Federal Minister for Religious Affairs Sardar Muhammad Yousaf revealed early work on the formation of an Islamic Education Commission (IEC) to regulate seminaries across the country. There has been no tangible progress on that front so far. Second, Federal Information Minister Pervaiz Rashid had to swallow his pride and apologize publicly for calling seminaries centers of ignorance and illiteracy. He clarified that he was referring to the handful of them involved in hate speech and illegal activities, but the backlash was powerful enough to make him reel.

On July 29, Lashkar-e-Jhangvi leader Malik Ishaq and several of his companions were killed in a gunfight with the police in Muzzafargarh city in southern Punjab. Less than three weeks later, Punjab Home Minister Col (r) Shuja Khanzada and 22 others were killed in a suicide attack at his home in Shadikhan. These two incidents, especially the latter, began a chain of events in August that ended in law-enforcement action against seminaries across the country.

On August 3, Sindh Police chief Ghulam Haider Jamali told his men to compile a list of registered and unregistered seminaries in the province in 15 days. On August 6 and 7, Punjab police carried out search operations in seminaries in Lahore, Multan, Faisalabad, Gujranwala and Bahawalpur. In the capital territory of Islamabad, Inspector General Tahir Alam Khan vowed to monitor traffic coming in and out of the 329 seminaries in the city. On August 26, it was reported that 703 unregistered seminaries and mosque schools in the tribal belt were soon to be blacklisted – the first major step towards the goal of regulation of seminaries. In KP, under Inspector General Nasir Durrani, police has taken action against 1,250 violations of the loudspeaker act and hate speech.

But in a controversial statement on August 26, Punjab Law Minister Rana Sanaullah said no seminaries in Punjab had any links with extremism.

Earlier, on August 7, the Pakistan Ulema Council issued a code of conduct for new admissions in seminaries, suggesting a softening stance towards regulation. The code includes provisions for maintaining accurate records, rejecting foreigners without credentials, extra-curricular activities, security precautions, an enhanced curriculum to include conventional education, rules for loudspeaker use, and discouraging sectarianism and other forms of hate speech.

Historically, the registration of seminaries has been a contentious subject. The political will to deal with the issue may have existed, but the ground realities, such as fierce opposition from the right, have compelled various governments to backtrack. That finally seems to be changing. It remains to be seen if this momentum will continue.

The author is a journalist and serves as a Senior Research Fellow at the Center for Research and Security Studies, Islamabad. He holds a Master’s degree in strategic communications from Ithaca College, NY.

Email: zeeshan[dot]salahuddin[at]gmail.com

Twitter: @zeesalahuddin