“Clearly, the outlook for our ineffective political democrats is not bright at the moment, and the word ‘politician’ is rapidly becoming a term of ridicule and disgust,” I wrote in an earlier article in The Friday Times.

One cannot help but notice the outbursts of anger on the Internet, where there seems to be virtually a competition in demanding that this or the other major penalty be visited on those terrible creatures, the politicians (other than those of the PTI, of course). There are chuckles of delight at the embarrassment of our former elected prime minister, and drooling at the mouth in anticipation of what could happen to our former president. Photos of General ‘Bobby’ Sharif – who is said to be a modest, publicity-shy person – are ubiquitous on print and electronic media. And, of course, it is held that the security establishment is calling the shots where defence, foreign affairs, and national security policies are concerned. To add to things, the sister of one of our major parliamentarians, one whose democratic credentials are considered impeccable, is said to have gone up to the good General and demanded that he should “save the country”. The sentiment is widely shared.

Our drawing-room philosophers contend: the politicians are corrupt and incompetent, and it is time for the army to take over and run things properly (as if our previous experiences on that score demonstrate the validity of such expectations).

Will we soon hear the boots of 101 Brigade marching up the Constitution Avenue? Is someone in Rawalpindi already composing his “My Dear Countrymen” speech? To answer that question, let us look at the circumstances surrounding the previous military coups this country has suffered, and see if there are any parallels with today’s situation.

In 1958, our first prospective general elections had been announced, party tickets had been awarded and there was considerable political enthusiasm across the country – especially in our former eastern Wing. Despite this, and risking enormous unpopularity, the army struck, first on 7th October, when President General Mirza sacked Prime Minister Noon, and then on 27th October, when General Ayub sent President Mirza packing. While the cancelation of the long-awaited elections and abrogation of the Constitution must have been immensely unpopular steps at the time, Ayub’s coup was received with enthusiasm and his decade-plus in power is, by many, still regarded as a ‘golden page’ in our history.

The point is that in the varying circumstances of nations, there are situations in which a military putsch may well be regarded positively, as Ayub’s was. I would suggest that there are at least three kinds of military seizures of power. There are the coups that overthrow tyrannical or horrifically incompetent regimes and bring into power ideologically driven leaders who are seen as liberators or nation-builders by their peoples. The examples of Nasser of Egypt, Peron of Argentina, or Ataturk of Turkey come to mind. The second kind are the counter-revolutionary putschists, who support retrograde ideologies and are boosted into power by malignant vested interests. Think of Suharto of Indonesia, Pinochet of Chile, and Ziaul Haq of evil memory and you will recognize the species.

There is yet a third kind of military seizure of power – the coup for reasons of simple personal ambition: “It’s my gun, so I’m in charge!” Think of Abacha of Nigeria, Banzer of Bolivia, Noriega of Panama, Idi Amin of Uganda, or Rawlings of Ghana.

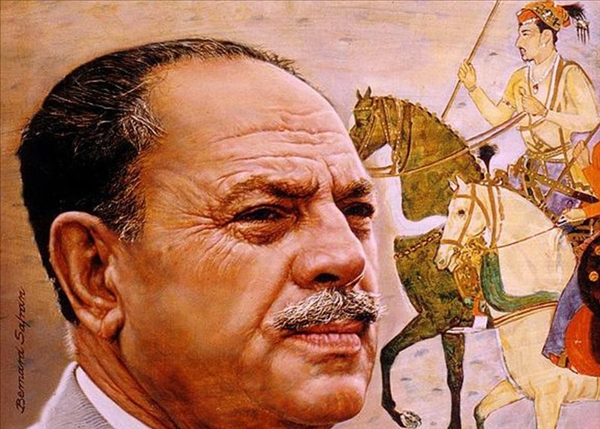

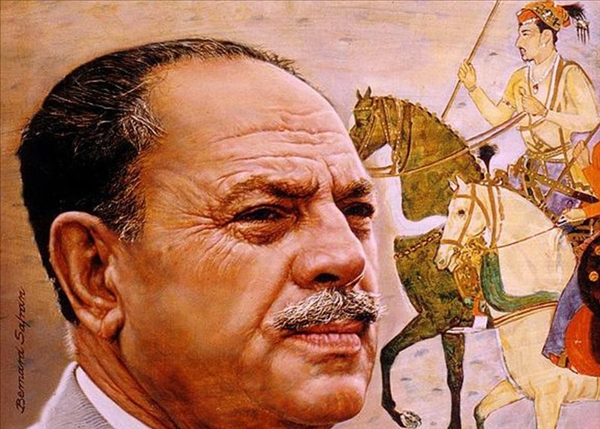

Ayub Khan belonged to the first kind – an ideologically driven visionary, who seized power in order to implement his vision. As quite candidly revealed in his very readable autobiography ‘Friends not Masters’, our first Pakistani military chief put down his ideas as to “what is wrong with the country and what can be done to put things right” as far back as a sleepless October night in London in 1954.

Like most ideologues, whether of the left or of the right, Ayub had a vision and believed in it – the vision of a prosperous, well-governed nation emerging as a result of developmental capitalism implemented under the paternalistic overview of effective government bureaucrats who did not pander to popular sentiment. And this vision, with all its merits and all its failings and blind spots, would drive the country for the eleven years from 1958 to 1969.

Yahya Khan was another matter. He was a personally ambitious man who happened to occupy the seat that commanded all that weaponry. Since he had only a limited guiding vision of his own, he tried to pander to all opinions, ending up in political stalemate, genocide, civil war, invasion and dismemberment of Pakistan.

In General Zia, one sees... no, not the ideologue. He is the classic counter-revolutionary, brought into power by the many powerful groups alienated by Bhutto’s socialist policies, arrogance, and abrasiveness. And cloaked behind the obscurantism of his religious protestations, Zia ruthlessly undid Bhutto’s legacy. We will skip over the ambitious Musharraf, who overthrew the Constitution merely because he was losing his job, and who had neither the stature of an Ayub nor the malignancy of a Zia.

And there you have it. Do any of those situations, or those personalities, bear a resemblance to the circumstances or principal actors of today? I believe no – not when the fact of constitutional rule has been overwhelmingly accepted and endorsed. A broadly democratic consensus has survived the violent civil war with the Taliban, the fecklessness of many of our own politicos, the jack-in-the-box antics of Dr Tahirul Qari, and Imran Khan’s dharnas. Today, there is a pervasive belief in the value and necessity of institutionalized rule, even if the modes of institutional interaction are still evolving and taking shape. There is no more room for ‘men on horseback’. There is no sound of marching boots.

It is the extraordinary mess created by previous ‘men on horseback’ – most especially Generals Ziaul Haq and Aslam Baig, as well as their coteries of civilian collaborators, and the ambitions of the US and Saudi intelligence services – that General Raheel Sharif and the Army have set about the task of cleaning up. They are doing quite well, even if there is still much to be done. On the other hand, let us appreciate the need to more clearly define the perimeters of the military’s task and to ensure firmer, more competent, and more institutionalized handling of foreign affairs. What needs to be guarded against is, simply, Mission Creep.

“The only maxim of a free government should be to trust no man living with power to endanger the public liberty.”

– John Adams, the second US president and eminent Constitutionalist.

One cannot help but notice the outbursts of anger on the Internet, where there seems to be virtually a competition in demanding that this or the other major penalty be visited on those terrible creatures, the politicians (other than those of the PTI, of course). There are chuckles of delight at the embarrassment of our former elected prime minister, and drooling at the mouth in anticipation of what could happen to our former president. Photos of General ‘Bobby’ Sharif – who is said to be a modest, publicity-shy person – are ubiquitous on print and electronic media. And, of course, it is held that the security establishment is calling the shots where defence, foreign affairs, and national security policies are concerned. To add to things, the sister of one of our major parliamentarians, one whose democratic credentials are considered impeccable, is said to have gone up to the good General and demanded that he should “save the country”. The sentiment is widely shared.

Our drawing-room philosophers contend: the politicians are corrupt and incompetent, and it is time for the army to take over and run things properly (as if our previous experiences on that score demonstrate the validity of such expectations).

Will we soon hear the boots of 101 Brigade marching up the Constitution Avenue? Is someone in Rawalpindi already composing his “My Dear Countrymen” speech? To answer that question, let us look at the circumstances surrounding the previous military coups this country has suffered, and see if there are any parallels with today’s situation.

"It's my gun, so I'm in charge!"

In 1958, our first prospective general elections had been announced, party tickets had been awarded and there was considerable political enthusiasm across the country – especially in our former eastern Wing. Despite this, and risking enormous unpopularity, the army struck, first on 7th October, when President General Mirza sacked Prime Minister Noon, and then on 27th October, when General Ayub sent President Mirza packing. While the cancelation of the long-awaited elections and abrogation of the Constitution must have been immensely unpopular steps at the time, Ayub’s coup was received with enthusiasm and his decade-plus in power is, by many, still regarded as a ‘golden page’ in our history.

The point is that in the varying circumstances of nations, there are situations in which a military putsch may well be regarded positively, as Ayub’s was. I would suggest that there are at least three kinds of military seizures of power. There are the coups that overthrow tyrannical or horrifically incompetent regimes and bring into power ideologically driven leaders who are seen as liberators or nation-builders by their peoples. The examples of Nasser of Egypt, Peron of Argentina, or Ataturk of Turkey come to mind. The second kind are the counter-revolutionary putschists, who support retrograde ideologies and are boosted into power by malignant vested interests. Think of Suharto of Indonesia, Pinochet of Chile, and Ziaul Haq of evil memory and you will recognize the species.

Musharraf had neither the stature of Ayub nor the malignancy of Zia

There is yet a third kind of military seizure of power – the coup for reasons of simple personal ambition: “It’s my gun, so I’m in charge!” Think of Abacha of Nigeria, Banzer of Bolivia, Noriega of Panama, Idi Amin of Uganda, or Rawlings of Ghana.

Ayub Khan belonged to the first kind – an ideologically driven visionary, who seized power in order to implement his vision. As quite candidly revealed in his very readable autobiography ‘Friends not Masters’, our first Pakistani military chief put down his ideas as to “what is wrong with the country and what can be done to put things right” as far back as a sleepless October night in London in 1954.

Like most ideologues, whether of the left or of the right, Ayub had a vision and believed in it – the vision of a prosperous, well-governed nation emerging as a result of developmental capitalism implemented under the paternalistic overview of effective government bureaucrats who did not pander to popular sentiment. And this vision, with all its merits and all its failings and blind spots, would drive the country for the eleven years from 1958 to 1969.

Yahya Khan was another matter. He was a personally ambitious man who happened to occupy the seat that commanded all that weaponry. Since he had only a limited guiding vision of his own, he tried to pander to all opinions, ending up in political stalemate, genocide, civil war, invasion and dismemberment of Pakistan.

In General Zia, one sees... no, not the ideologue. He is the classic counter-revolutionary, brought into power by the many powerful groups alienated by Bhutto’s socialist policies, arrogance, and abrasiveness. And cloaked behind the obscurantism of his religious protestations, Zia ruthlessly undid Bhutto’s legacy. We will skip over the ambitious Musharraf, who overthrew the Constitution merely because he was losing his job, and who had neither the stature of an Ayub nor the malignancy of a Zia.

And there you have it. Do any of those situations, or those personalities, bear a resemblance to the circumstances or principal actors of today? I believe no – not when the fact of constitutional rule has been overwhelmingly accepted and endorsed. A broadly democratic consensus has survived the violent civil war with the Taliban, the fecklessness of many of our own politicos, the jack-in-the-box antics of Dr Tahirul Qari, and Imran Khan’s dharnas. Today, there is a pervasive belief in the value and necessity of institutionalized rule, even if the modes of institutional interaction are still evolving and taking shape. There is no more room for ‘men on horseback’. There is no sound of marching boots.

It is the extraordinary mess created by previous ‘men on horseback’ – most especially Generals Ziaul Haq and Aslam Baig, as well as their coteries of civilian collaborators, and the ambitions of the US and Saudi intelligence services – that General Raheel Sharif and the Army have set about the task of cleaning up. They are doing quite well, even if there is still much to be done. On the other hand, let us appreciate the need to more clearly define the perimeters of the military’s task and to ensure firmer, more competent, and more institutionalized handling of foreign affairs. What needs to be guarded against is, simply, Mission Creep.

“The only maxim of a free government should be to trust no man living with power to endanger the public liberty.”

– John Adams, the second US president and eminent Constitutionalist.