Budgets in Pakistan tend to be a lackluster affair – the same tale of overly ambitious and ultimately missed targets, a reluctance to confront entrenched interests, and clumsy explanations for why things didn’t work out as planned in the previous year. Mid-term budgets are least likely to break this mould. Nevertheless, the government had some good news to report this year (most notably, lower inflation and increased foreign exchange reserves), and has emerged politically stronger after the potential crisis of the dharna last year. This was a good opportunity to push through some meaningful initiatives. Lets see if that happened.

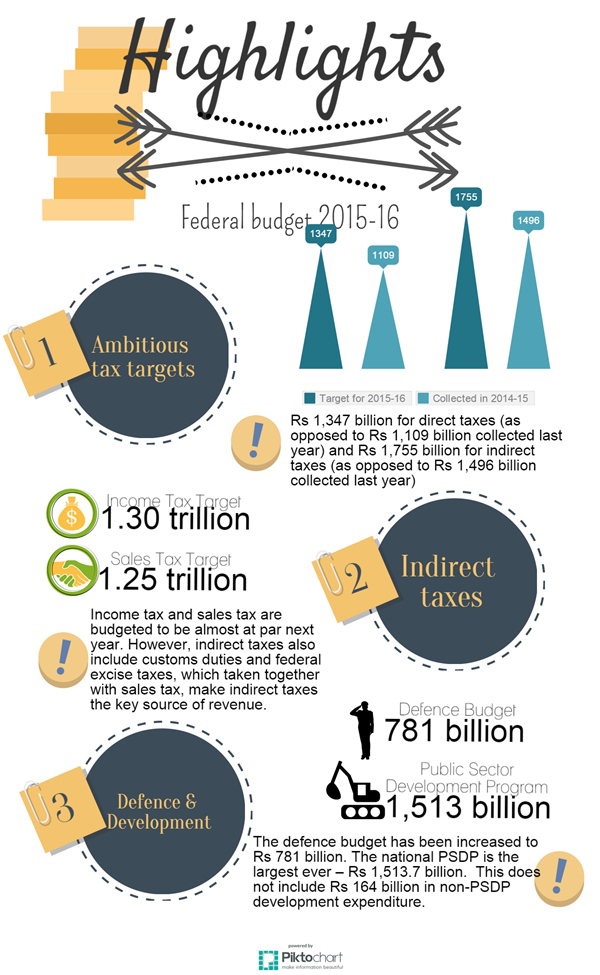

First, the resource position. The Federal Board of Revenue (FBR) missed both its direct and indirect tax targets this year, with direct taxes falling short by Rs 70 billion (collection of Rs 1.11 trillion as opposed to a budgeted Rs 1.18 trillion), and indirect taxes by Rs 134 billion. Sales tax, customs duties and income tax all took hits, but the government has still gone ahead with posting even more ambitious collection targets for the coming year (Rs 1.3 trillion for income tax and Rs 1.25 trillion for sales tax), although last year’s collection for these taxes barely crossed Rs 1 trillion. The Finance Minister’s speech indicates that the government hopes to reach these targets by expanding the scheme of differential taxation for filers and non-filers (an excellent idea), and by increasing sales tax rate on a range of goods and services including mobile phones (a highly regressive policy). At the same time, the government continues to make its constituents happy by continuing with the policy of reducing the corporate income tax rate by 1% a year till it hits 30% in another three years.

To sum up, the policy of relying on indirect taxes will continue unabated. The good news is, though, that non-filers of tax returns will now be squeezed further. In a curious twist, neither the budget speech nor the budget summary documents say anything about the controversial Gas Infrastructure Development Cess (GIDC) which the government expects will yield Rs 145 billion in the coming year. There are legal obstacles in the way of taxing against this head, and its strange that it did not even merit a clarification.

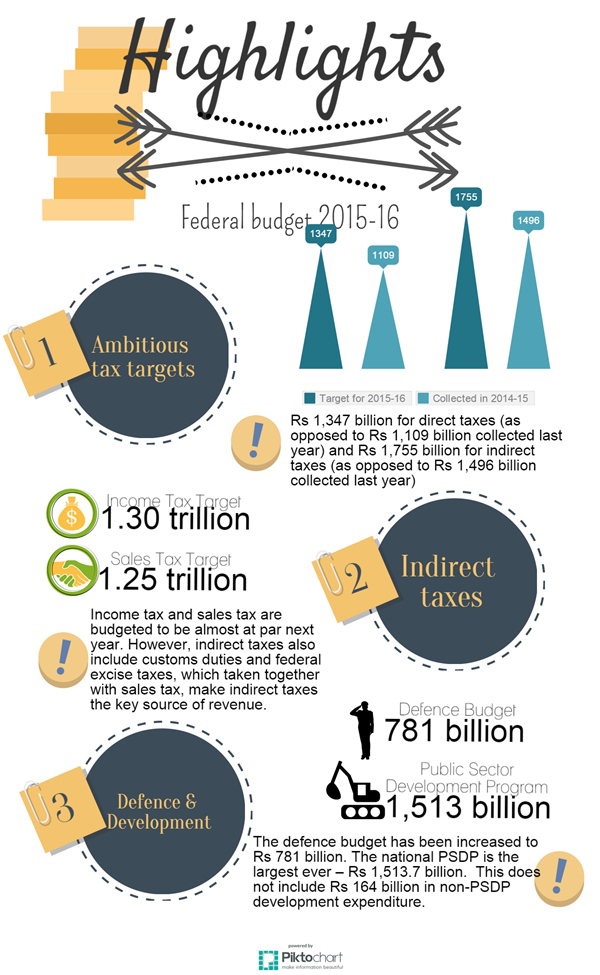

And now on to current expenditure. Traditionally, the government has little wiggle room here as debt service payments alone take up a non-negotiable 40% of current spending. Defense expenditure has now been left far behind at about 22% of current expenditure, but that again is more or less inviolable – in fact it has been increased to almost a quarter of current expenditure in the coming year. With 65% of current expenditure thus covered, and the rest, consisting of mainly government official’s salaries and pensions, there are only one or two heads where the government can maneuver. As in previous years, this year again, the government is claiming a substantial cut in the subsidy budget in the coming year – budgeting Rs 137.6 billion as opposed to the Rs 243 billion that was actually spent last year. Once again, the emphasis is on reducing the inter-disco tariff differential paid out to WAPDA and KESC. There is no doubt that there has been a substantial cut in payments made against this head (in 2012, subsidies to WAPDA and KESC were higher than the defense budget!) but it may not be realistic to engineer such a big reduction again. But given the rigidity of expenditures under different heads, there is no choice but to make these two utilities, particularly WAPDA, pick up the losses accruing to their distribution companies or wings.

Which brings us to the development budget – the section where the government really demonstrates its vision for the economy. As the Public Sector Development Programme (PSDP) stands now, this vision looks like a bit of a pipe dream. To begin with, the size of the federal PSDP has been increased by 27% for the coming year. There’s lots going on here – the Diamer Bhasha Dam, the Lahore-Karachi Motorway, and the development of Gwadar, as well as other projects under the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor. Those are the big ticket items. There is also all the usual clutter which is parked outside the PSDP, but within the category of development spending – skill development programs and business loans for youth, internship programs, the laptop scheme, crop loans and livestock insurance etc. All of this adds up to a PSDP of Rs 1.5 trillion, plus a further Rs 164 billion for the non-PSDP schemes, which is almost half of current expenditure. Given that the tax-GDP ratio is very much stuck at 10%, and tax revenues barely cover current expenditure (excluding interest liabilities), this programme is extremely ambitious.

In terms of a vision, the PSDP demonstrates where the current dispensation’s priorities lie – and it’s no mystery that high visibility, big bang infrastructure is the order of the day. Some of this will be funded from foreign sources – the China-Pakistan economic corridor projects for example are expected to bring in up to $46 billion in funding in the coming years. The rest will be funded mainly from non-bank borrowing (issuing public debt), some borrowing from commercial banks (thankfully, no plans to borrow from the State Bank), and by pressurizing provinces to yield “surpluses” – essentially cutting down on the less glamorous schemes in provincial development budgets. Social sector spending has seen little change, in spite of the nod to the MDG goals through a Rs 20 billion project in the federal PSDP, which would have been better housed in provinces.

Large infrastructure projects can yield excellent returns in the medium to long term if run efficiently, with a tight rein on deadlines and costs. Without these controls in place, they can end up being white elephants. One hopes that the government will do something about strengthening regulation before embarking on an ambitious infrastructure development programme.

Overall, the budget reflects some positive developments, but stays with the Pakistani tradition of being overly ambitious. For example, it is true that the government has implemented an excellent initiative in distinguishing between filers and non-filers of taxes for a range of applicable taxes and fees; has curtailed borrowing from the State Bank; and has kept a lid on current expenditure.

At the same time, its reliance on indirect taxes remains intact; the strengthening of the regulatory regime has yet to yield significant returns (the tax-GDP ratio remains unchanged); the increase in foreign exchange reserves has come not from export receipts but from capital inflows through multilaterals; it has not pushed through significant energy sector reform; and its fascination with infrastructure to the detriment of social sector investment remains intact. The IMF’s conditions will be met, and the country will attract foreign investment at least from a few select sources. Its human resource capability is unlikely to see significant improvements.

First, the resource position. The Federal Board of Revenue (FBR) missed both its direct and indirect tax targets this year, with direct taxes falling short by Rs 70 billion (collection of Rs 1.11 trillion as opposed to a budgeted Rs 1.18 trillion), and indirect taxes by Rs 134 billion. Sales tax, customs duties and income tax all took hits, but the government has still gone ahead with posting even more ambitious collection targets for the coming year (Rs 1.3 trillion for income tax and Rs 1.25 trillion for sales tax), although last year’s collection for these taxes barely crossed Rs 1 trillion. The Finance Minister’s speech indicates that the government hopes to reach these targets by expanding the scheme of differential taxation for filers and non-filers (an excellent idea), and by increasing sales tax rate on a range of goods and services including mobile phones (a highly regressive policy). At the same time, the government continues to make its constituents happy by continuing with the policy of reducing the corporate income tax rate by 1% a year till it hits 30% in another three years.

Non-filers of tax returns will be squeezed further

To sum up, the policy of relying on indirect taxes will continue unabated. The good news is, though, that non-filers of tax returns will now be squeezed further. In a curious twist, neither the budget speech nor the budget summary documents say anything about the controversial Gas Infrastructure Development Cess (GIDC) which the government expects will yield Rs 145 billion in the coming year. There are legal obstacles in the way of taxing against this head, and its strange that it did not even merit a clarification.

And now on to current expenditure. Traditionally, the government has little wiggle room here as debt service payments alone take up a non-negotiable 40% of current spending. Defense expenditure has now been left far behind at about 22% of current expenditure, but that again is more or less inviolable – in fact it has been increased to almost a quarter of current expenditure in the coming year. With 65% of current expenditure thus covered, and the rest, consisting of mainly government official’s salaries and pensions, there are only one or two heads where the government can maneuver. As in previous years, this year again, the government is claiming a substantial cut in the subsidy budget in the coming year – budgeting Rs 137.6 billion as opposed to the Rs 243 billion that was actually spent last year. Once again, the emphasis is on reducing the inter-disco tariff differential paid out to WAPDA and KESC. There is no doubt that there has been a substantial cut in payments made against this head (in 2012, subsidies to WAPDA and KESC were higher than the defense budget!) but it may not be realistic to engineer such a big reduction again. But given the rigidity of expenditures under different heads, there is no choice but to make these two utilities, particularly WAPDA, pick up the losses accruing to their distribution companies or wings.

Which brings us to the development budget – the section where the government really demonstrates its vision for the economy. As the Public Sector Development Programme (PSDP) stands now, this vision looks like a bit of a pipe dream. To begin with, the size of the federal PSDP has been increased by 27% for the coming year. There’s lots going on here – the Diamer Bhasha Dam, the Lahore-Karachi Motorway, and the development of Gwadar, as well as other projects under the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor. Those are the big ticket items. There is also all the usual clutter which is parked outside the PSDP, but within the category of development spending – skill development programs and business loans for youth, internship programs, the laptop scheme, crop loans and livestock insurance etc. All of this adds up to a PSDP of Rs 1.5 trillion, plus a further Rs 164 billion for the non-PSDP schemes, which is almost half of current expenditure. Given that the tax-GDP ratio is very much stuck at 10%, and tax revenues barely cover current expenditure (excluding interest liabilities), this programme is extremely ambitious.

In terms of a vision, the PSDP demonstrates where the current dispensation’s priorities lie – and it’s no mystery that high visibility, big bang infrastructure is the order of the day. Some of this will be funded from foreign sources – the China-Pakistan economic corridor projects for example are expected to bring in up to $46 billion in funding in the coming years. The rest will be funded mainly from non-bank borrowing (issuing public debt), some borrowing from commercial banks (thankfully, no plans to borrow from the State Bank), and by pressurizing provinces to yield “surpluses” – essentially cutting down on the less glamorous schemes in provincial development budgets. Social sector spending has seen little change, in spite of the nod to the MDG goals through a Rs 20 billion project in the federal PSDP, which would have been better housed in provinces.

In 2012, subsidies to WAPDA and KESC were higher than the defense budget

Large infrastructure projects can yield excellent returns in the medium to long term if run efficiently, with a tight rein on deadlines and costs. Without these controls in place, they can end up being white elephants. One hopes that the government will do something about strengthening regulation before embarking on an ambitious infrastructure development programme.

Overall, the budget reflects some positive developments, but stays with the Pakistani tradition of being overly ambitious. For example, it is true that the government has implemented an excellent initiative in distinguishing between filers and non-filers of taxes for a range of applicable taxes and fees; has curtailed borrowing from the State Bank; and has kept a lid on current expenditure.

At the same time, its reliance on indirect taxes remains intact; the strengthening of the regulatory regime has yet to yield significant returns (the tax-GDP ratio remains unchanged); the increase in foreign exchange reserves has come not from export receipts but from capital inflows through multilaterals; it has not pushed through significant energy sector reform; and its fascination with infrastructure to the detriment of social sector investment remains intact. The IMF’s conditions will be met, and the country will attract foreign investment at least from a few select sources. Its human resource capability is unlikely to see significant improvements.