Edgware Road is one of my favourite hangouts in London: late nights spent gossiping with friends over sheesha and Moroccan tea; the familiar buzz emanating from lines of Turkish and Middle Eastern eateries and tea-houses. It isn’t that other areas of London are necessarily less exotic, but this place is awake the whole night – and this is rare for a European city.

About ten miles from this corner of Edgware Road is the “other” Edgware – better known for being the haunt of one of Pakistan’s most talked-about politicians than for the quality of its doner kebabs. It is from here that Altaf Hussain runs his – as the MQM is wont to call it – “international secretariat”. Rating meters determine the electronic media’s interests and 75 percent of these meters are concentrated in the city of Karachi. Little wonder then, that Karachi dominates the electronic media. And when it’s about Karachi, it’s about Altaf Hussain and the MQM.

Since 1987, when the MQM swept the local body polls in Karachi, it has dominated the city’s complicated politics. But Karachi’s problems are not new – any more than the MQM is in hot water for the first time. The law and order situation here has never been, strictly speaking, ideal – it is only the scale that has shifted from one period to the next. Since independence, the city’s Urdu-speaking population has dominated both Pakistani politics (seven out of ten Pakistani Prime Ministers were Urdu-speaking migrants) as well as the bureaucracy.

The pendulum swung the other way in the 1970s with the rise of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, when the PPP introduced a quota system favouring the ethnic Sindhi population to placate the provincial nationalists. It worked – the PPP emerged as the largest political force in Sindh – but also ended up alienating the migrant population, large numbers of who lived in Karachi, Hyderabad and other cities of Sindh. The Karachi political scene of those days was dominated by the Jamaat-e-Islami under Maulana Maudoodi. After his death, the party’s leadership shifted to a Punjabi, Mian Tufail Mohammad, which further alienated the Urdu-speaking population from the mainstream Pakistani leadership.

It was at this juncture that Altaf Hussain, Tariq Azeem, Farooq Sattar and others laid the basis of the All Pakistan Mohajir Students Federation. This fundamentally ethnic body played the Mohajir card as the basis of its politics. By the mid-1980s, the military leadership was nurturing Altaf Hussain and company as a counter-force to the PPP in Karachi and other cities of Sindh. The MQM’s landslide victory in 1987 owed more than a little to the invisible hand of the army. The party used this chance to consolidate its political (and militant) role in Karachi and Hyderabad: in less than three years, it became a force to be reckoned with. It is interesting that the “top five” who formed the MQM with Altaf Hussain were killed in mysterious circumstances and that the party (despite being in office at the time) did nothing to apprehend their killers.

Fast forward to the general election in 2013. On 22 May, an irate Altaf Hussain addressed a general meeting of the MQM and commanded his workers to thrash a group of Rabita Committee members because they had failed to deliver and deliberately not divulged the details of various alleged criminal activities to their leader. This led to a split in the ranks: Mustafa Kamal, who had parted ways with Altaf Hussain before the elections, now joined Anees Qaim Khani and Saleem Shahzad, both representing the Qaim Khani and Bihari factions of the migrant population. Raza Haroon, too, was side-lined and only Farooq Sattar was allowed to reassume his position.

Meanwhile, the larger picture had also begun to change. The new army chief, General Raheel Sharif, chose to discontinue the lukewarm, laid-back policies of his predecessor, General Ashfaq Kayani, and troops were ordered to eliminate all forms of militancy. Karachi was handed over to a troika comprising Lieutenant-General Rizwan Akhtar, Lieutenant-General Naveed Mukhtar and Major-General Bilal Akbar, and a huge operation based on the intelligence gathered was launched, leading to a rumpus in the MQM camp.

The MQM itself was already beleaguered by internal politics. Party member Nabeel Gabol, a non-Urdu-speaking MNA, had been asked to resign, following which elections were held to contest his vacant seat. The constituency of NA246 was a traditional MQM stronghold and the poll results reflected this. The MQM played its ethnic card once again and Altaf Hussain and co. reclaimed the seat.

But the party’s problems are far from over in the wake of Saulat Mirza’s execution, Altaf Hussain’s demand that the MQM governor of Sindh resign, and the arrest of suspects in the Imran Farooq murder case. The only way that the MQM can remain intact as a party is if Altaf Hussain nominates his successor from Karachi – and not from London. Otherwise, it almost certainly stands to lose its impact as a political force.

Follow the author @fawadchaudhry

About ten miles from this corner of Edgware Road is the “other” Edgware – better known for being the haunt of one of Pakistan’s most talked-about politicians than for the quality of its doner kebabs. It is from here that Altaf Hussain runs his – as the MQM is wont to call it – “international secretariat”. Rating meters determine the electronic media’s interests and 75 percent of these meters are concentrated in the city of Karachi. Little wonder then, that Karachi dominates the electronic media. And when it’s about Karachi, it’s about Altaf Hussain and the MQM.

Since 1987, when the MQM swept the local body polls in Karachi, it has dominated the city’s complicated politics. But Karachi’s problems are not new – any more than the MQM is in hot water for the first time. The law and order situation here has never been, strictly speaking, ideal – it is only the scale that has shifted from one period to the next. Since independence, the city’s Urdu-speaking population has dominated both Pakistani politics (seven out of ten Pakistani Prime Ministers were Urdu-speaking migrants) as well as the bureaucracy.

When it's about Karachi, it's about Altaf Hussain and the MQM

The pendulum swung the other way in the 1970s with the rise of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, when the PPP introduced a quota system favouring the ethnic Sindhi population to placate the provincial nationalists. It worked – the PPP emerged as the largest political force in Sindh – but also ended up alienating the migrant population, large numbers of who lived in Karachi, Hyderabad and other cities of Sindh. The Karachi political scene of those days was dominated by the Jamaat-e-Islami under Maulana Maudoodi. After his death, the party’s leadership shifted to a Punjabi, Mian Tufail Mohammad, which further alienated the Urdu-speaking population from the mainstream Pakistani leadership.

It was at this juncture that Altaf Hussain, Tariq Azeem, Farooq Sattar and others laid the basis of the All Pakistan Mohajir Students Federation. This fundamentally ethnic body played the Mohajir card as the basis of its politics. By the mid-1980s, the military leadership was nurturing Altaf Hussain and company as a counter-force to the PPP in Karachi and other cities of Sindh. The MQM’s landslide victory in 1987 owed more than a little to the invisible hand of the army. The party used this chance to consolidate its political (and militant) role in Karachi and Hyderabad: in less than three years, it became a force to be reckoned with. It is interesting that the “top five” who formed the MQM with Altaf Hussain were killed in mysterious circumstances and that the party (despite being in office at the time) did nothing to apprehend their killers.

Fast forward to the general election in 2013. On 22 May, an irate Altaf Hussain addressed a general meeting of the MQM and commanded his workers to thrash a group of Rabita Committee members because they had failed to deliver and deliberately not divulged the details of various alleged criminal activities to their leader. This led to a split in the ranks: Mustafa Kamal, who had parted ways with Altaf Hussain before the elections, now joined Anees Qaim Khani and Saleem Shahzad, both representing the Qaim Khani and Bihari factions of the migrant population. Raza Haroon, too, was side-lined and only Farooq Sattar was allowed to reassume his position.

Meanwhile, the larger picture had also begun to change. The new army chief, General Raheel Sharif, chose to discontinue the lukewarm, laid-back policies of his predecessor, General Ashfaq Kayani, and troops were ordered to eliminate all forms of militancy. Karachi was handed over to a troika comprising Lieutenant-General Rizwan Akhtar, Lieutenant-General Naveed Mukhtar and Major-General Bilal Akbar, and a huge operation based on the intelligence gathered was launched, leading to a rumpus in the MQM camp.

The MQM itself was already beleaguered by internal politics. Party member Nabeel Gabol, a non-Urdu-speaking MNA, had been asked to resign, following which elections were held to contest his vacant seat. The constituency of NA246 was a traditional MQM stronghold and the poll results reflected this. The MQM played its ethnic card once again and Altaf Hussain and co. reclaimed the seat.

But the party’s problems are far from over in the wake of Saulat Mirza’s execution, Altaf Hussain’s demand that the MQM governor of Sindh resign, and the arrest of suspects in the Imran Farooq murder case. The only way that the MQM can remain intact as a party is if Altaf Hussain nominates his successor from Karachi – and not from London. Otherwise, it almost certainly stands to lose its impact as a political force.

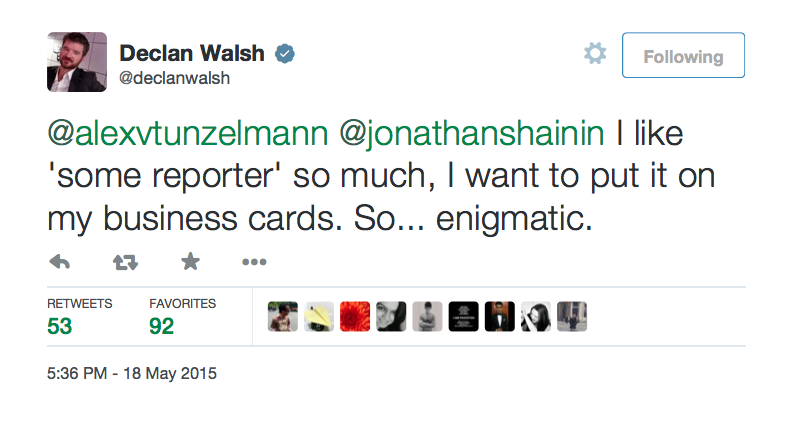

Twitterati

Follow the author @fawadchaudhry