Dealing with a declining reputation in the face of growing crime, Pakistani police does not seem to be equipped to meet the new challenges of counterterrorism and counterinsurgency. But the same police is seen as a glowing image of professionalism in law enforcement in its various international peacekeeping operations.

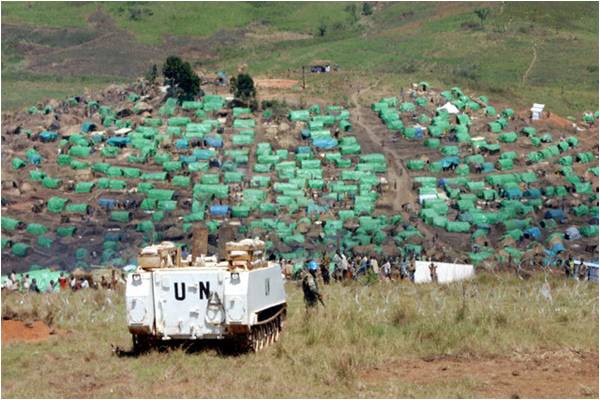

The chief of the United Nations himself acknowledged Pakistan’s services, saying it was impossible to speak about the history of UN peacekeeping without highlighting the Islamabad’s contribution. UN General Secretary Ban Ki-moon visited Islamabad in the summer of 2013 and declared that Pakistan was number one of more than 100 countries that contribute troops and police for United Nations peacekeeping missions. Back then, 8,000 of Pakistan’s men and women were serving in complex and challenging missions, including Darfur, Haiti, and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Such praise from the UN chief should have encouraged the government to not only to contribute more personnel in such missions but also utilize the experience of trained individuals to share their knowledge and experience with others. What actually happened was contrary to this. Three months after Ban Ki-Moon’s visit, the interior ministry placed a ban on sending peacekeepers from the police corp. As reported, Interior Minister Chaudhry Nisar had passed instructions to higher authorities to ban foreign postings of policemen, not even sending them on foreign trainings. The ministry officials said that the decision was made because of internal security problems. Pakistan was facing a war-zone situation, so the police need not be deployed to other conflict zones.

The UN program had been essential for the Police to get hands-on experience in volatile areas, and trained officials are valuable assets. Training, as Mr Ban had pointed out in his address, is a strategic investment in peacekeeping. Deployment in international peacekeeping provides exposure and networking opportunities critical for career development of police officers, but it opens them to new research and techniques vital for crime fighting and counterterrorism – skills that Pakistan police direly needs.

An extensive report prepared by the Asia Society says that both the number and complexity of the tasks mandated to United Nations Police (UNPOL) had grown dramatically. A segment of the report prepared by Andrew Carpenter points out that, “Pakistan appears to have failed to fully grasp and exploit the value and potential of its former UNPOL officers for its own domestic policing needs.”

The pre-deployment selection tests and procedures and the quality of the average UNPOL officer from Pakistan was significantly higher than his or her average national counterpart even before deployment. The report emphasizes that “police officers from Pakistan who have been deployed in UN peace operations will have enhanced their professionalism not only through exposure to standards of excellence in international policing and specialized training, but also through day-to-day interaction with their host state counterparts and fellow international UNPOL colleagues. Working as part of a UNPOL component, Pakistani police offers are given the opportunity to meet and learn form people from many different backgrounds and cultures.”

There was some resistance to the decision to ban such postings, and not just because there were 232 police officers waiting for their positions since 2011. A letter from the New York consulate suggested that the decision to postpone the deployment of police peacekeepers “will give a chance to other countries form South Asia like Bangladesh, India and Nepal” to contribute. The letter said that Pakistan would lose the stature achieved after hectic efforts and its redemption would take at least a span of three to five years. “It is strongly suggested that we may revisit our decision and continue to send police peacekeepers to the UN mission.”

The chief of general staff also wrote a letter to the interior ministry asking them to review the ban. The letter said the decision might raise unnecessary alarm about Pakistan’s internal security at the international level, adding that, “vacancies once surrendered in a particular mission cannot be secured in future.” It said that UN always has the leverage to select individuals from a large pool of nominations received from the entire world including war torn countries like Congo, Mali and Sudan.

In the post-Cold War world, UNPOL peacekeepers were required to undertake more dynamic roles of mentoring, training, and advising their host state counterparts to build up domestic operational capability in less peaceful contexts. It later got involved in reforming, restructuring, and rebuilding institutional capacity.

According to a brief prepared by United States Institute of Peace, a Washington based think tank, Pakistan was the third largest contributor to UN peacekeeping missions after India and Bangladesh. The brief mentioned that as of April last year, 588 Pakistani policemen and 7,359 soldiers were taking part in peacekeeping operations. A total of 8,938 Pakistani police officers have been deployed in UN missions since 1992, when Pakistani police went to Cambodia.

From 1992 to 2013, Pakistani police deployment increased from 35 to 766 annually. The UN peacekeepers returning to Pakistan were replicating the best practices of peacekeeping at home. They continue to identify themselves as UN peacekeepers while serving in the police by displaying their UN police medals and insignia on their uniforms. During their time as peacekeepers, the blue helmets operate within a system in which respect for human rights is seen as the cornerstone of police work, the report says, and they undergo human rights training for their missions. On returning home, local communities tend to respect former peacekeepers for their perceived integrity in an environment where human rights violations in regular police work are commonplace. Former peacekeepers perceive themselves as politically neutral and as agents of the rule of law.

The brief, originally prepared in June 2014 by Muhammad Quraish Khan, a police veteran of 13 years who served in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa as a director of the forensics division, suggests that international peacekeeping and protection of civilians should be included in the police training curriculum, and that the experience of former peacekeepers needed to be utilized in police reforms initiatives, in devising training modules and delivering training. With some 400,000 policemen at work, says the report, it is not logical to argue that allowing 700 police to participate in overseas peacekeeping at any one time would undercut the department’s capabilities.

Former Pakistani police official and chair of the Department of Regional and Analytical Studies at the National Defense University in Washington Prof Hassan Abbas says that it was an internal rift between the district management group (DMG) officials and the police that resulted in a ban on foreign aassignments for the police. “If an ongoing war is an excuse, then the authorities should have put out a uniform policy and banned army personnel from going on international assignments as well,” he says.

Prof Abbas says international support for anti-terrorism operations in Pakistan in the last decade was largely geared towards the defense sector, and very little of that support ever reached the police. This created a situation in which military control trumped local knowledge and know-how. Pakistan does not even have a mechanism to better utilize the services of police officers who went on Fulbright scholarships and Hubert Humphrey fellowships in the United States in recent years, he says.

Prof Abbas urges the government to lift the ban on international deployments, and provide police with critical technology and training it needs. The ban has cost the country a growing good reputation at the global level, willingness to fight crime and terrorism through training, and thousands of dollars of payments each year. It is an opportunity lost at a time when it is most needed.

The chief of the United Nations himself acknowledged Pakistan’s services, saying it was impossible to speak about the history of UN peacekeeping without highlighting the Islamabad’s contribution. UN General Secretary Ban Ki-moon visited Islamabad in the summer of 2013 and declared that Pakistan was number one of more than 100 countries that contribute troops and police for United Nations peacekeeping missions. Back then, 8,000 of Pakistan’s men and women were serving in complex and challenging missions, including Darfur, Haiti, and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Such praise from the UN chief should have encouraged the government to not only to contribute more personnel in such missions but also utilize the experience of trained individuals to share their knowledge and experience with others. What actually happened was contrary to this. Three months after Ban Ki-Moon’s visit, the interior ministry placed a ban on sending peacekeepers from the police corp. As reported, Interior Minister Chaudhry Nisar had passed instructions to higher authorities to ban foreign postings of policemen, not even sending them on foreign trainings. The ministry officials said that the decision was made because of internal security problems. Pakistan was facing a war-zone situation, so the police need not be deployed to other conflict zones.

The UN program had been essential for the Police to get hands-on experience in volatile areas, and trained officials are valuable assets. Training, as Mr Ban had pointed out in his address, is a strategic investment in peacekeeping. Deployment in international peacekeeping provides exposure and networking opportunities critical for career development of police officers, but it opens them to new research and techniques vital for crime fighting and counterterrorism – skills that Pakistan police direly needs.

It is an opportunity lost at a time when it is most needed

An extensive report prepared by the Asia Society says that both the number and complexity of the tasks mandated to United Nations Police (UNPOL) had grown dramatically. A segment of the report prepared by Andrew Carpenter points out that, “Pakistan appears to have failed to fully grasp and exploit the value and potential of its former UNPOL officers for its own domestic policing needs.”

The pre-deployment selection tests and procedures and the quality of the average UNPOL officer from Pakistan was significantly higher than his or her average national counterpart even before deployment. The report emphasizes that “police officers from Pakistan who have been deployed in UN peace operations will have enhanced their professionalism not only through exposure to standards of excellence in international policing and specialized training, but also through day-to-day interaction with their host state counterparts and fellow international UNPOL colleagues. Working as part of a UNPOL component, Pakistani police offers are given the opportunity to meet and learn form people from many different backgrounds and cultures.”

There was some resistance to the decision to ban such postings, and not just because there were 232 police officers waiting for their positions since 2011. A letter from the New York consulate suggested that the decision to postpone the deployment of police peacekeepers “will give a chance to other countries form South Asia like Bangladesh, India and Nepal” to contribute. The letter said that Pakistan would lose the stature achieved after hectic efforts and its redemption would take at least a span of three to five years. “It is strongly suggested that we may revisit our decision and continue to send police peacekeepers to the UN mission.”

The chief of general staff also wrote a letter to the interior ministry asking them to review the ban. The letter said the decision might raise unnecessary alarm about Pakistan’s internal security at the international level, adding that, “vacancies once surrendered in a particular mission cannot be secured in future.” It said that UN always has the leverage to select individuals from a large pool of nominations received from the entire world including war torn countries like Congo, Mali and Sudan.

In the post-Cold War world, UNPOL peacekeepers were required to undertake more dynamic roles of mentoring, training, and advising their host state counterparts to build up domestic operational capability in less peaceful contexts. It later got involved in reforming, restructuring, and rebuilding institutional capacity.

According to a brief prepared by United States Institute of Peace, a Washington based think tank, Pakistan was the third largest contributor to UN peacekeeping missions after India and Bangladesh. The brief mentioned that as of April last year, 588 Pakistani policemen and 7,359 soldiers were taking part in peacekeeping operations. A total of 8,938 Pakistani police officers have been deployed in UN missions since 1992, when Pakistani police went to Cambodia.

From 1992 to 2013, Pakistani police deployment increased from 35 to 766 annually. The UN peacekeepers returning to Pakistan were replicating the best practices of peacekeeping at home. They continue to identify themselves as UN peacekeepers while serving in the police by displaying their UN police medals and insignia on their uniforms. During their time as peacekeepers, the blue helmets operate within a system in which respect for human rights is seen as the cornerstone of police work, the report says, and they undergo human rights training for their missions. On returning home, local communities tend to respect former peacekeepers for their perceived integrity in an environment where human rights violations in regular police work are commonplace. Former peacekeepers perceive themselves as politically neutral and as agents of the rule of law.

The brief, originally prepared in June 2014 by Muhammad Quraish Khan, a police veteran of 13 years who served in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa as a director of the forensics division, suggests that international peacekeeping and protection of civilians should be included in the police training curriculum, and that the experience of former peacekeepers needed to be utilized in police reforms initiatives, in devising training modules and delivering training. With some 400,000 policemen at work, says the report, it is not logical to argue that allowing 700 police to participate in overseas peacekeeping at any one time would undercut the department’s capabilities.

Former Pakistani police official and chair of the Department of Regional and Analytical Studies at the National Defense University in Washington Prof Hassan Abbas says that it was an internal rift between the district management group (DMG) officials and the police that resulted in a ban on foreign aassignments for the police. “If an ongoing war is an excuse, then the authorities should have put out a uniform policy and banned army personnel from going on international assignments as well,” he says.

Prof Abbas says international support for anti-terrorism operations in Pakistan in the last decade was largely geared towards the defense sector, and very little of that support ever reached the police. This created a situation in which military control trumped local knowledge and know-how. Pakistan does not even have a mechanism to better utilize the services of police officers who went on Fulbright scholarships and Hubert Humphrey fellowships in the United States in recent years, he says.

Prof Abbas urges the government to lift the ban on international deployments, and provide police with critical technology and training it needs. The ban has cost the country a growing good reputation at the global level, willingness to fight crime and terrorism through training, and thousands of dollars of payments each year. It is an opportunity lost at a time when it is most needed.