She danced the dance of flames and fire,

And the dance of swords and spears;

She danced the dance of stars and the dance of space,

And then she danced the dance of flowers in the wind.

– Kahlil Gibran, The Wanderer

It takes courage to work in the arts given that artists tend to express so much of themselves in their work. This is especially true of the art of dance. I have often come away from dance performances, whether ballet, salsa or classical dance, feeling uplifted. Is it the music or the movement or that the dancers use the physical self as a form of expression to which one can connect?

Dance has existed for centuries. It is associated not only with culture and history but also used to express stories, feelings and moods. In some communities, it makes tradition and brings people together, such as the traditional folk troika in Russia. In some African and Latin American cultures, dance even predates language and was a way of passing down stories from one generation to another, similar to our oral tradition of the dastaan or stories. In others, it showcases the beauty of the human form, but also entertains (belly dancing in the Middle East). Though essentially linked to freedom and letting go, dance is often based on very precise disciplined movements, requiring hours of skill and commitment.

In many cultures, dance is linked to divinity and spirituality. Dancers often talk about connecting within and being able to connect to something bigger, shedding one’s sense of self. Shiva, the Hindu god, is associated with the iconic Nataraja and the cycles of creation and destruction. Dance is also often used to depict battles between good and evil. When visiting Bali a few years ago, I was transfixed by the culture of temple dances. In the magical town of Ubud, every evening, Balinese temple dancers showcase the Mahabharat or other fables. The setting is dramatic in fire-lit ancient stone temples with lyrical gamalan chimes and bells and under starlit skies. The cast typically includes most of the community – women and children of all ages dressed up in exotic batik with extravagant gold head ornaments. There is magic in this type of dance – conveying history, art and music through a group experience.

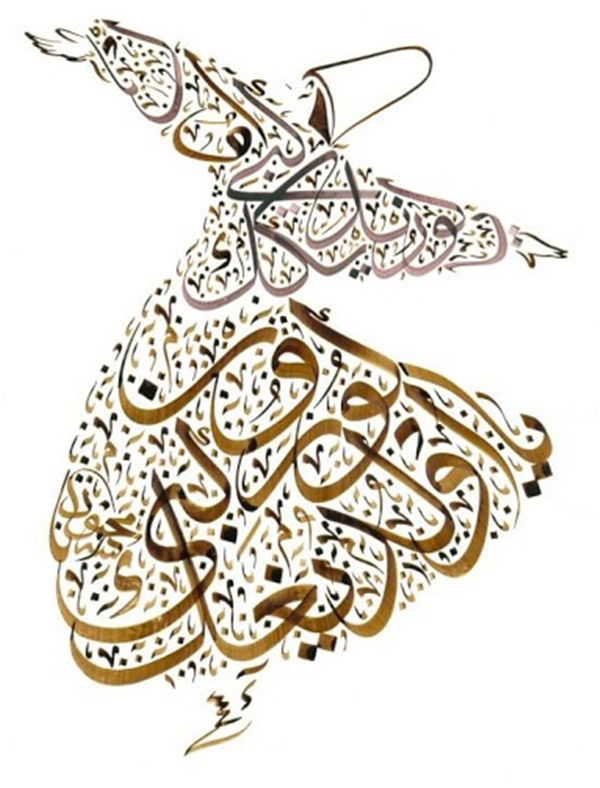

The concept of whirling dervishes in Sufi Islam is similar: such meditation through dance has an interesting concept. The dervish seeks to abandon the ego (nafs) by focusing on the music and spinning in circles from left to right until he or she can reach a higher state of perfection (kemal). The movement is associated with planets orbiting the sun and, in this case, the body spirals around its centre: the beating heart.

This image is expressed so beautifully by Jalaluddin Rumi: “Dancing is not getting up any time painlessly like a speck of dust blown around in the wind. Dancing is when you rise above both worlds, tearing your heart to pieces and giving up your soul.” A stunning image if one pauses to think of the symbolism: to embrace humanity with love and tolerance.

Some of my happiest childhood memories are of us dancing in our pyjamas with abandon

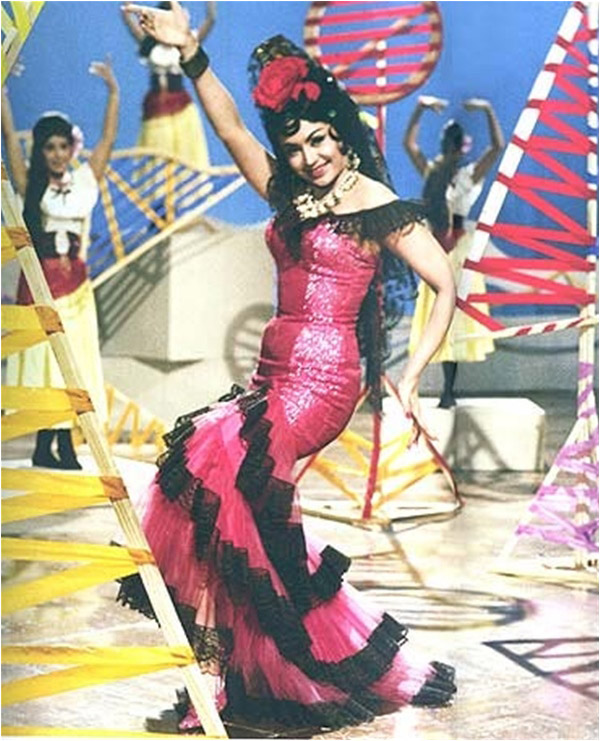

As young children, we often experimented with dance, though perhaps not in such a spiritual manner as the whirling sufis or Balinese temple dancers. My siblings and I could not wait for our parents to leave the house for a dinner party in order to re-enact the latest Bollywood dance numbers. Helen, the prevailing siren, was our muse and we would happily cover the floors with talcum powder to let loose. Some of my happiest childhood memories are of us dancing in our pyjamas with abandon to all sorts of music.

Over the years at home, we graduated to dances from movies. Who can forget the inimitable Patrick Swayze teaching the salsa and the merengue in Dirty Dancing? The movie spawned an entire generation of closet dirty-dancers in the 1980s (though I wish more of the boys in our generation in Lahore had learned how to dance like Swayze). As an adult, I have often regretted not learning classical dance. I now wish I could turn back time and substitute the many hours I had devoted to Bollywood to a more artistic and disciplined art form like Bharat Natyam.

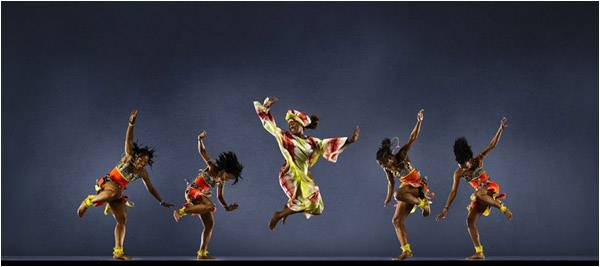

Dance in all its forms can be a wonderful experience. In Washington, DC, a Lebanese friend has introduced us to the magical world of tap dancing through a dance school set up by a spirited Ethiopian woman who wants to showcase different forms of dance as a form of cultural expression. There, every week, my ten-year-old dances under the tutelage of Joseph, a larger-than-life African-American dance teacher with a Sikh-like turban. He is the visual embodiment of the genie from Aladdin. In the precious hour of practice, he imparts a love of music and dance, shares the talent he has picked up from Broadway while spontaneously doing little tap dances himself. The atmosphere in the studio is infectious – of music, joy and the power of movement.

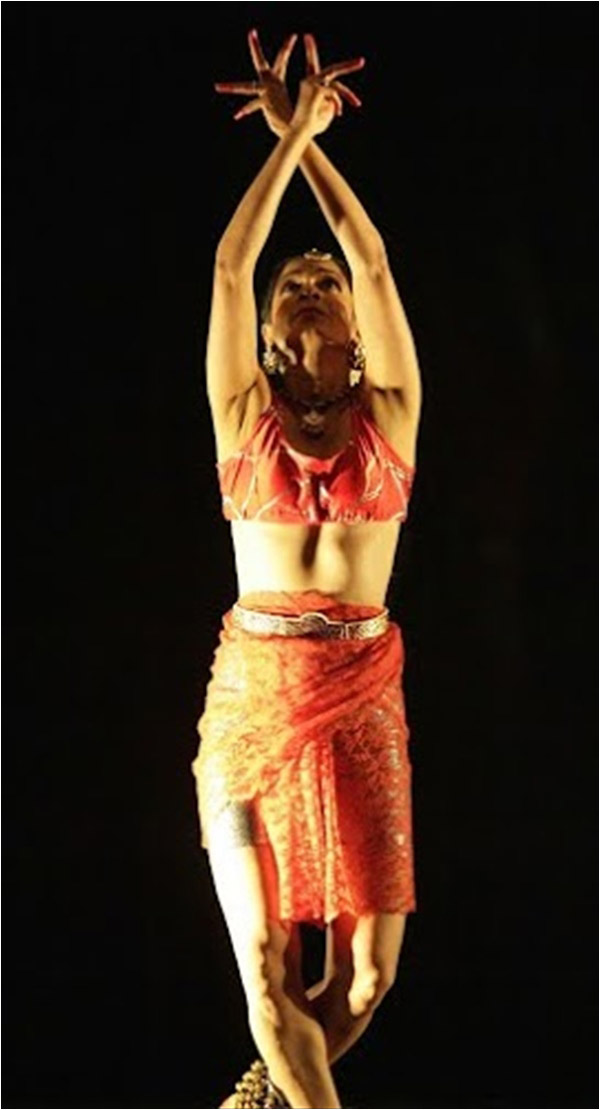

To celebrate the inner child in me who loved to dance, I recently attended the Atlas Performing Arts festival in Washington, DC, which celebrates the arts in many forms. Showcased as part of the festival was dancer Tehreema Mitha’s bold performance, which covered a fusion of traditional dance with soulful North Indian ragas composed for the performance. She is a face of Pakistan rarely seen in the US. Unfortunately, the opportunity to see dance in a public space is becoming increasingly limited in Pakistan. Mitha’s dancing career is well documented in Pakistan, partly due to the remarkable reputation of her mother, Indu Mitha, who was one of the earliest proponents of classical Bharat Natyam.

Mitha’s own work aims to build on the classical roots of her culture and layer it with modern experience, but by telling stories that have universal appeal. In her words: “My work is not fusion. It is what we are today, now. I refuse to be tidily slotted and labelled as an ‘Ethnic’, ‘Oriental’ or ‘Traditional’ South Asian dancer. We are part of a dynamic ever-changing world culture in which, if we do not lose our roots and sense of self, we can discover so much more.” Another Russian dancer at a show in Washington, DC, expressed the same sentiment while explaining the Russian “khoro vid”: she said she had realised how universal the circular sun dance was when visiting Taiwan – that people had the same symbolism and stories even though their worlds were so far apart in reality. Dance helps to bridge those worlds.

After these performances, I was particularly struck with how others express their culture through dance. We have a long-standing history of folk dance (be it the Punjabi bhangra or the flower dance of Baltistan), but do not tend to express ourselves through this medium, which is a lost opportunity. So, with that resolve, I will dust off my old dancing shoes and take out the talcum powder. Except that, at this age, there are some activities best done behind closed doors. I can’t wait for the children to leave the house.