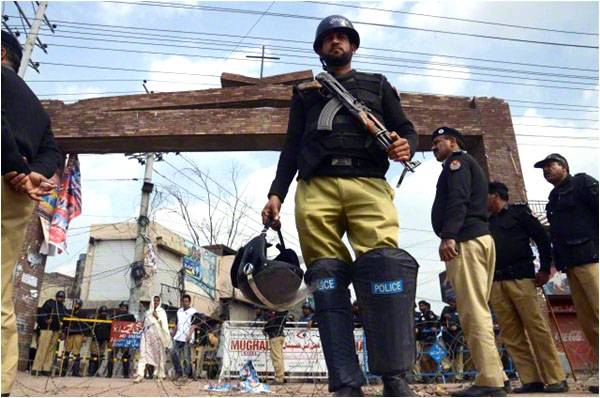

The attacks on two churches in the Youhanabad area of Lahore, and the public lynching of two people the crowd deemed suspects highlights several alarming facts. These intersect, coalesce and amalgamate to create a highly volatile and unpredictable atmosphere which then self-perpetuates, relentlessly continuing the cycle.

Step one in this cycle is the failure of the state and its institutions. If this was a singular failure, a tumor that could be treated or excised, it would be a different story. But this is a systemic problem, one that has permeated every aspect of state functions and institutions. First and foremost, the state is completely unable to protect its citizens. The most basic and fundamental tenant of the social contract is that citizens give up certain rights in exchange for certain freedoms, principal among them the right to live and work peacefully.

Citizens of today’s Pakistan, especially minorities, are under siege from a faction of the extremist strain that pollutes our collective national ideology and washes our streets in the blood of the innocent. Since the enactment of the National Action plan (NAP), in the wake of the atrocious attack on schoolchildren in Peshawar, minorities have been especially vulnerable against attacks. The enemy is already well-aware that the state response will be meek at best, so minorities remain easy fodder for their quest for relevancy. The state’s response has been immediate condemnation, public avowing to avenge the fallen, and then quietly waiting for the next catastrophe, to repeat these tried and tested tactics. Our politicians, our law enforcement agencies, and even our judiciary, are unable to protect our citizens and provide speedy justice. This breeds distrust, and inculcates a sense of abandonment and helplessness.

Step two of this cycle stems from the massive trust deficit in the citizens, once again, especially minorities. The public faith in state institutions, especially those that are responsible for security and justice, is fleeting at best, and non-existent at worst. This deficit manifests itself in a wide variety of ways, depending on a large range of factors including their socio-economic status, resource availability, and religious disposition.

The manifestation can be in the form of an alarming rate of brain-drain away from Pakistan, as people are chased away, or make the choice to escape before anything untoward happens. It can be in the form of public unrest, blockades, protests and civil strife. It can also take the shape, as it did this past weekend, of the most deplorable and sickening form of mob justice. Even then, it was the latest in a series of public lynchings, committed by people of different faiths, for different reasons. Only one thread remains common: none of them had faith in the authorities to do the right thing.

This argument makes no excuse for the mobs’ behavior or their despicable disposition, but merely suggests that taking justice and the law into their own hands implies a gaping mistrust in Pakistan’s institutional capacity to provide security for its citizens, and failing that, provide justice.

Step three of this cycle is the state’s response outside the ambit of providing justice. When the social contract is violated, the state must recognize the grievance. In most cases, this does happen, hollow and inconsiderate as it may be. But then, the state must provide compensation, ongoing social support, and a wide social security net for the survivors of the departed. In Pakistan, this normally amounts to the chief minister or similar official announcing a lump sum being given to the bereaved family.

At present, Balochistan is the only province has legislation in place to ensure that civilians are compensated for their losses in a holistic manner, and catered to if their social contract is violated. The Institute of Social and Policy Sciences, a research organization based in Islamabad, has been instrumental in helping formulating such law, and believes the same can be replicated in the other provinces and regions as well. Their belief is not misplaced, as mechanisms already exist that can be duplicated. The law enforcement agencies in Pakistan has compensation structures that, while not exemplary, are closer in spirit to a more comprehensive form of compensation for the aggrieved. Yet, somehow, only one province has managed to pass the bill to legalize and formalize this crucial practice, and that too only recently. Coupled with the massive backlog of cases pending in our courts, as well as the glacial pace of the justice delivery service, it is no wonder that the lack of these laws continue to perpetuate the distrust the public have in state institutions.

The culmination of these steps is a state that seems to have laws, rules and regulations designed to uphold the social contract, but limited capacity to execute and near negligible political will. The public, in turn, spirals deeper into this sense of neglect at the hands of the state, resulting in civil unrest and a complete desertion of the rule of law and respect for fundamental human rights, which further deteriorates the situation. The trust gap is ever-widening, and the state must act to overcome this chasm through a) a capable security apparatus, especially the police, and b) legislating on civilian victim compensation, as they have in Balochistan. Without the political will to take these steps, and the impetus to earn the public trust, this is a battle that eventually everyone loses.

The author is a journalist and a Senior Research Fellow at the Center for Research and Security Studies, Islamabad. He holds a Master’s degree in strategic communications from Ithaca College, NY.

Email: zeeshan[dot]salahuddin[at]gmail.com

Twitter: @zeesalahuddin

Step one in this cycle is the failure of the state and its institutions. If this was a singular failure, a tumor that could be treated or excised, it would be a different story. But this is a systemic problem, one that has permeated every aspect of state functions and institutions. First and foremost, the state is completely unable to protect its citizens. The most basic and fundamental tenant of the social contract is that citizens give up certain rights in exchange for certain freedoms, principal among them the right to live and work peacefully.

Citizens of today’s Pakistan, especially minorities, are under siege from a faction of the extremist strain that pollutes our collective national ideology and washes our streets in the blood of the innocent. Since the enactment of the National Action plan (NAP), in the wake of the atrocious attack on schoolchildren in Peshawar, minorities have been especially vulnerable against attacks. The enemy is already well-aware that the state response will be meek at best, so minorities remain easy fodder for their quest for relevancy. The state’s response has been immediate condemnation, public avowing to avenge the fallen, and then quietly waiting for the next catastrophe, to repeat these tried and tested tactics. Our politicians, our law enforcement agencies, and even our judiciary, are unable to protect our citizens and provide speedy justice. This breeds distrust, and inculcates a sense of abandonment and helplessness.

Step two of this cycle stems from the massive trust deficit in the citizens, once again, especially minorities. The public faith in state institutions, especially those that are responsible for security and justice, is fleeting at best, and non-existent at worst. This deficit manifests itself in a wide variety of ways, depending on a large range of factors including their socio-economic status, resource availability, and religious disposition.

The manifestation can be in the form of an alarming rate of brain-drain away from Pakistan, as people are chased away, or make the choice to escape before anything untoward happens. It can be in the form of public unrest, blockades, protests and civil strife. It can also take the shape, as it did this past weekend, of the most deplorable and sickening form of mob justice. Even then, it was the latest in a series of public lynchings, committed by people of different faiths, for different reasons. Only one thread remains common: none of them had faith in the authorities to do the right thing.

This argument makes no excuse for the mobs’ behavior or their despicable disposition, but merely suggests that taking justice and the law into their own hands implies a gaping mistrust in Pakistan’s institutional capacity to provide security for its citizens, and failing that, provide justice.

Step three of this cycle is the state’s response outside the ambit of providing justice. When the social contract is violated, the state must recognize the grievance. In most cases, this does happen, hollow and inconsiderate as it may be. But then, the state must provide compensation, ongoing social support, and a wide social security net for the survivors of the departed. In Pakistan, this normally amounts to the chief minister or similar official announcing a lump sum being given to the bereaved family.

At present, Balochistan is the only province has legislation in place to ensure that civilians are compensated for their losses in a holistic manner, and catered to if their social contract is violated. The Institute of Social and Policy Sciences, a research organization based in Islamabad, has been instrumental in helping formulating such law, and believes the same can be replicated in the other provinces and regions as well. Their belief is not misplaced, as mechanisms already exist that can be duplicated. The law enforcement agencies in Pakistan has compensation structures that, while not exemplary, are closer in spirit to a more comprehensive form of compensation for the aggrieved. Yet, somehow, only one province has managed to pass the bill to legalize and formalize this crucial practice, and that too only recently. Coupled with the massive backlog of cases pending in our courts, as well as the glacial pace of the justice delivery service, it is no wonder that the lack of these laws continue to perpetuate the distrust the public have in state institutions.

The culmination of these steps is a state that seems to have laws, rules and regulations designed to uphold the social contract, but limited capacity to execute and near negligible political will. The public, in turn, spirals deeper into this sense of neglect at the hands of the state, resulting in civil unrest and a complete desertion of the rule of law and respect for fundamental human rights, which further deteriorates the situation. The trust gap is ever-widening, and the state must act to overcome this chasm through a) a capable security apparatus, especially the police, and b) legislating on civilian victim compensation, as they have in Balochistan. Without the political will to take these steps, and the impetus to earn the public trust, this is a battle that eventually everyone loses.

The author is a journalist and a Senior Research Fellow at the Center for Research and Security Studies, Islamabad. He holds a Master’s degree in strategic communications from Ithaca College, NY.

Email: zeeshan[dot]salahuddin[at]gmail.com

Twitter: @zeesalahuddin