(and occasionally the unpublishable)

Publishers can follow either the Duke of Wellington’s testy advice, “Publish and be damned!” or Ashok Chopra’s more pragmatic example: “Publish and befriend.”

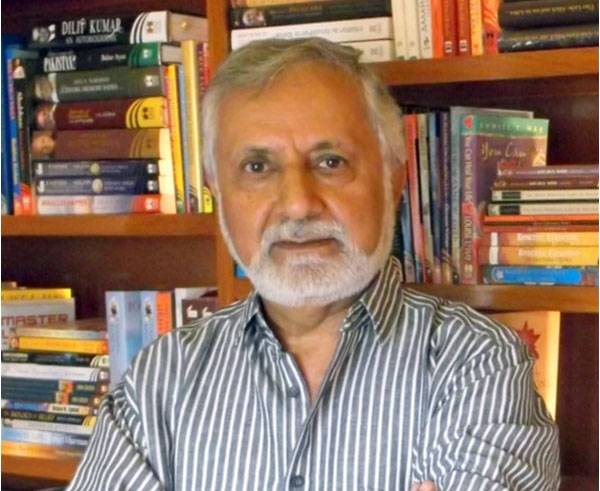

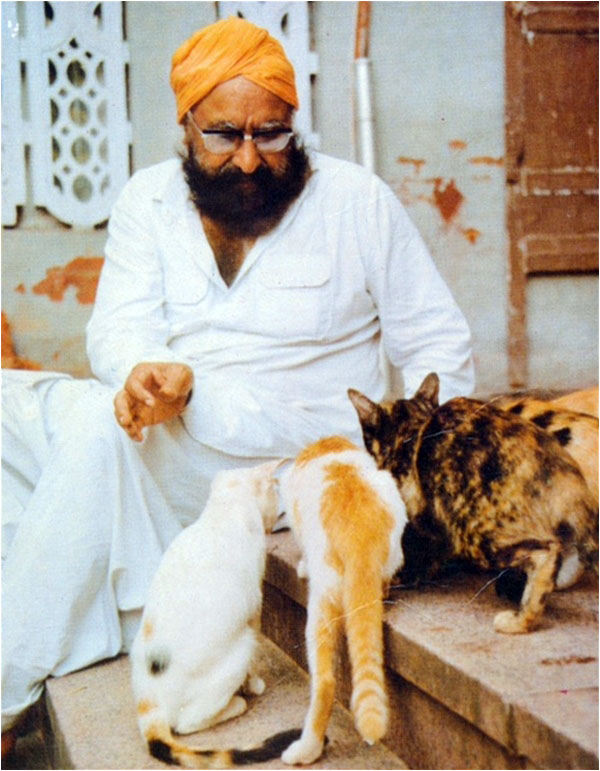

For the past 40 years, Ashok Chopra has been at the receiving end of manuscripts, first as an editor and then as publisher. He has been bombarded by unsolicited manuscripts from scribbling hopefuls, coaxed them out of reluctant first-time authors such as Dilip Kumar, solicited them from successful authors such as Khushwant Singh and Shobhaa Dé, and occasionally, rarely, rued the ones that got away (Dev Anand, scooped up by Penguin).

Now, after a lifetime in the trade, Chopra has taken up his pen, not to edit or to sharpen someone else’s text, but to record his own experiences. His book A Scrapbook of Memories unfurls like a contemporary Bayeux tapestry of India’s literati. Everyone who wanted to be anyone is there. And all but a nameless few are still his friends.

Chopra reveals his authors’ idiosyncrasies with discretion, their writing habits with patience, and their impatience with genteel derision: Uma Vasudev – “a beautiful oriental octopus [who] takes a long, very long, time to finish a book, but once over, she wants to have it published ‘yesterday’.” Gita Mehta, who wrote the hugely successful Karma Cola in three weeks and then laboured for eight years to finish Raj. Patwant Singh, who would take “two years writing a book but would want it published within two months.” I. S. Johar’s salacious, indiscreet, and (for Ashok) unpublishable memoirs that would have made Casanova blush. Dev Anand’s 964-page handwritten manuscript, for which he wanted a ‘blind’ bid from publishers before allowing them access to it (Chopra refused and lost the deal.) And the legendary Dilip Kumar who made Chopra wait 24 years before completing his memoirs. They appeared finally in June 2014 under the title The Substance and the Shadow: An Autobiography, by which time Dilip sahib was in his 92nd year.

Among his successes, Chopra savours his collaboration with J. N. Dixit, one of India’s strategic diplomats, on My South Block Years: Memoirs of a Foreign Secretary, and with General V. P. Malik on Kargil: From Surprise to Victory. Like him, they were disciplined professionals in their own fields, which may have underpinned Chopra’s respect for them.

Chopra sensibly avoids discussing an author’s craft. He does, however, provide fascinating insights into their writing habits: Saadat Hasan Manto’s obsession with fountain pens; Ismat Chughtai at her munim’s desk playing “cards with her left hand and writing with her right”; Mulk Raj Anand perched on a special pedestal, “like a baby’s high-chair”; and Dominique Lapierre (co-author of Freedom at Midnight) and his fetish for “Parker Quink Permanent Black.”

Just as every author dreads rejection, every publisher fears a morning-after scare. Will the subject of the book refuse to accept it? Will publication precipitate long and costly litigation?

Chopra’s examples of such post-publication traumas reveal the dark face of Indian Venuses. Take Indira Gandhi’s curt, wounding dismissal of Dom Moraes’ biography of her even after he had personally presented her with a copy inscribed with optimistic poignancy, “For the subject of these words – Dom.” Or Lata Mangeshkar’s rejection of Raju Bharatan’s 386-page, sumptuously produced biography of her – not for being authoritative, but for not being authorized. Or Maneka Gandhi’s seven-year-long battle to have Khushwant Singh’s memoirs blocked because they described her expulsion from her mother-in-law’s house. Or Mother Teresa’s feud with Dominique Lapierre that caused him 15 years “of profound suffering.”

A good, readable book stands on its own. It does not need to be launched

Despite these often-fatal setbacks and the low print run (the average in India is 2,000 copies), Indian publishing has survived because it has a well-articulated chain of expertise that begins with an idea and ends with a book in the hands of a reader. A good, readable book, Chopra asserts, stands on its own. It does not need to be launched. It does no harm, though, for a book such as Admiral S. M. Nanda’s The Man Who Bombed Karachi: A Memoir to be launched on INS Vikrant or to see Mani Shankar Aiyar’s Pakistan Papers receive the benediction of the then Pakistani high commissioner, Riaz Hussain Khokhar.

In 2002, when tension between the two countries came to a boil, Chopra released J. N. Dixit’s India–Pakistan in War and Peace. While bullets flew across the enflamed border, copies of the book could not. They entered Pakistan via Europe.

Chopra analyses the Indian publishing industry with geometric precision. He cites the three points in the Indian publishing triangle: linkages with foreign publishers, the widespread popularity of English over regional languages, and the overwhelming demand (80%) for course books in higher education.

Only a man who knows the Indian market like the back of his wallet could observe: “In Mumbai, they only speak and read money. In Delhi there is money but no language, except officialese. In Kolkata there is little money, but a language with a strong base that communicates.”

As co-chairman and director, Chopra organizes the Khushwant Singh Literary Festival in Kasauli every October. It is one out of over 60 literary festivals held all over India. The granddaddy of these, held in Jaipur every January, started in 2006 with 100 attendees; this year, over 100,000 attended. It has become the Kumbh mela of India’s literary scene. The Lahore Literary Festival, despite being only three years old, has already attracted 75,000 adherents. This is a remarkable achievement in a city that has more bomb blasts than bookshops. Literary festivals such as these prove that the public still craves the written word, the uttered thought.

Ashok Chopra’s Memories is a fascinating, riveting read, faultless in construction, tone and content, moving without being mawkish. It concludes with an observation by the Argentinian scholar Alberto Manguel: “We read in order to be quiet.” Reading, Chopra adds, is “not a question of money or availability, but the moral strength to be alone ‘with the beating of one’s heart’.” In effect, to befriend oneself through a book.

A Scrapbook of Memories can be pre-ordered at Books & Beans or through Vanguard