The November 21 public gathering of the Pakistan Tehrik-e-Insaf (PTI) in Larkana district in the Sindh province – a traditional stronghold of Pakistan People’s Party (PPP) – has started a new debate. Will the PTI emerge as a substitute for the PPP in the province?

Independent political analysts say Tehrik-e-Insaf managed to show significant strength, and party workers Are confident it is set to make a big change.

“The successful gathering in Larkana showed that the people of Sindh have rejected the PPP as a status quo party, and now they are with the PTI,” said Nadir Akmal Legahri, the party’s Sindh president.

Commentators agree that the people of Sindh are disappointed by the policies of the ruling PPP. Murad Pandrani, a political analyst who writes in Sindhi language newspaper, said that the PTI is already making problems for the PPP in Sindh. “If PTI could organize three or four more successful gathering in the province, it could become an alternative political force,” he says.

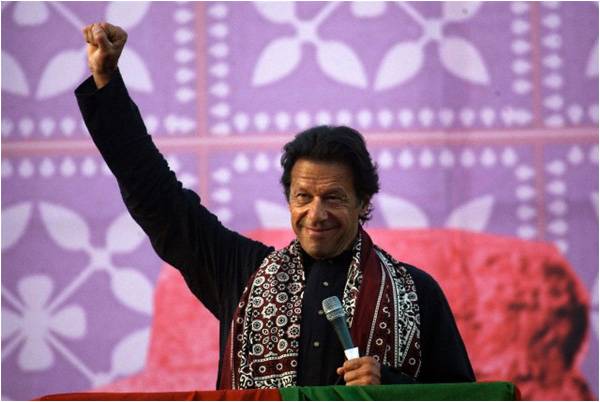

That is why PTI Chairman Imran Khan spoke mainly about the lack of development, the educational crisis and ‘ghost teachers’, the drought in Tharparkar, and the plight of religious minorities in the province, and openly opposed the construction of controversial Kalabagh Dam and division of Sindh province.

The influential Unar family – who are known for changing loyalties – organized the gathering in their native Ali Abad town. Candidates from the party have contested elections on the tickets of the PPP and Pakistan Muslim League-Quaid, and sometimes as independent candidates in the past.

Journalists in Larkana say choosing the Unars as the hosts was a bad decision. “Political leaders and elders from various tribes had concerns about attending a gathering on Unars’ land. The PTI leadership should have organized the activity in main Larkana city,” said a veteran journalist.

Some observers say that in its aggressive effort to make inroads in rural Sindh, the party is eying alliances with influential traditional politicians and feudal lords instead of gathering grassroots support.

“It is a wrong approach. The PML-N adopted the same strategy in Sindh and failed,” said Pandrani.

Background interviews with PTI’s Sindh leaders suggest that Shah Mehmood Qureshi, who is also a spiritual leader of the Ghousia Jamaat, is working on that strategy. “A number of key political figures from Sindh – including former chief ministers and federal ministers – were ready to join the PTI because of the efforts of Qureshi, but Leghari and his supporters held press conferences across the province opposing the inclusion of these leaders,” said a provincial leader of PTI in Karachi.

A number of veteran party members are wary of these traditional politicians and want the PTI leadership to develop a system of due diligence and some minimum criteria before inviting these ‘electables’ to join the party.

“Such politicians may help us win some constituencies, but we will lose goodwill in the larger cities like Karachi, Sukkur and Hyderabad, which are our core constituency,” said a central leader of the party in Karachi.

Three former chief ministers of Sindh – Liaquat Jatoi, Arbab Ghulam Rahim and Ghous Ali Shah – along with provincial chief of PML-Functional Saddaruddin Rashidi and former speaker of National Assembly Ilahi Baksh Soomro, also formed an anti-PPP alliance on November 24. Insiders say Qureshi was behind that development, and the alliance will support the PTI in Sindh.

The PTI leadership has not reached out to the Sindh’s nationalist parties, which have significant support in the province. Three major nationalist parties – the Sindh United Party led by Jalal Mehmood Shah, Ayaz Latif Palijo’s Qaumi Awami Tehrik, and Dr Qadir Magsi’s Sindh Tarraqi Pasand Party – supported the PML-N in the last elections, but are no longer close to it.

“Imran Khan has made a big mistake ignoring the Sindhi nationalist parties. They don’t have parliamentary presence but they have street power in the province,” said a Hyderabad-based journalist.

Most journalists do not agree with PTI’s complaints that the Sindh government created problems for the organizers of the public meeting. The PPP too is confident that the PTI cannot hurt its popularity with the help of what they call ‘traditional turncoats’. “PTI’s gathering in Larkana was a failure,” according to Sharjeel Memon, a key PPP leader and the provincial information minister. “PTI cannot misguide Sindhis with propaganda and forged, abusive allegations against other politicians.” He said it was not the first time political forces had united against his party in Sindh, but the people of the province had always voted for the PPP.

Many political observers agree with him. They believe it would be very difficult for the PTI to dent the popularity of the PPP despite their failures.

Hafeez Chachar, a veteran journalist and researcher, believes the PPP knows the Sindhi people in a way other political parties and alliances do not. “In the last elections, a ten-party alliance was formed against the PPP with the support of Sindhi nationalists, but it could not hurt the PPP.”

Independent political analysts say Tehrik-e-Insaf managed to show significant strength, and party workers Are confident it is set to make a big change.

“The successful gathering in Larkana showed that the people of Sindh have rejected the PPP as a status quo party, and now they are with the PTI,” said Nadir Akmal Legahri, the party’s Sindh president.

Commentators agree that the people of Sindh are disappointed by the policies of the ruling PPP. Murad Pandrani, a political analyst who writes in Sindhi language newspaper, said that the PTI is already making problems for the PPP in Sindh. “If PTI could organize three or four more successful gathering in the province, it could become an alternative political force,” he says.

That is why PTI Chairman Imran Khan spoke mainly about the lack of development, the educational crisis and ‘ghost teachers’, the drought in Tharparkar, and the plight of religious minorities in the province, and openly opposed the construction of controversial Kalabagh Dam and division of Sindh province.

The influential Unar family is known for changing loyalties

The influential Unar family – who are known for changing loyalties – organized the gathering in their native Ali Abad town. Candidates from the party have contested elections on the tickets of the PPP and Pakistan Muslim League-Quaid, and sometimes as independent candidates in the past.

Journalists in Larkana say choosing the Unars as the hosts was a bad decision. “Political leaders and elders from various tribes had concerns about attending a gathering on Unars’ land. The PTI leadership should have organized the activity in main Larkana city,” said a veteran journalist.

Some observers say that in its aggressive effort to make inroads in rural Sindh, the party is eying alliances with influential traditional politicians and feudal lords instead of gathering grassroots support.

“It is a wrong approach. The PML-N adopted the same strategy in Sindh and failed,” said Pandrani.

Background interviews with PTI’s Sindh leaders suggest that Shah Mehmood Qureshi, who is also a spiritual leader of the Ghousia Jamaat, is working on that strategy. “A number of key political figures from Sindh – including former chief ministers and federal ministers – were ready to join the PTI because of the efforts of Qureshi, but Leghari and his supporters held press conferences across the province opposing the inclusion of these leaders,” said a provincial leader of PTI in Karachi.

A number of veteran party members are wary of these traditional politicians and want the PTI leadership to develop a system of due diligence and some minimum criteria before inviting these ‘electables’ to join the party.

“Such politicians may help us win some constituencies, but we will lose goodwill in the larger cities like Karachi, Sukkur and Hyderabad, which are our core constituency,” said a central leader of the party in Karachi.

Three former chief ministers of Sindh – Liaquat Jatoi, Arbab Ghulam Rahim and Ghous Ali Shah – along with provincial chief of PML-Functional Saddaruddin Rashidi and former speaker of National Assembly Ilahi Baksh Soomro, also formed an anti-PPP alliance on November 24. Insiders say Qureshi was behind that development, and the alliance will support the PTI in Sindh.

The PTI leadership has not reached out to the Sindh’s nationalist parties, which have significant support in the province. Three major nationalist parties – the Sindh United Party led by Jalal Mehmood Shah, Ayaz Latif Palijo’s Qaumi Awami Tehrik, and Dr Qadir Magsi’s Sindh Tarraqi Pasand Party – supported the PML-N in the last elections, but are no longer close to it.

“Imran Khan has made a big mistake ignoring the Sindhi nationalist parties. They don’t have parliamentary presence but they have street power in the province,” said a Hyderabad-based journalist.

Most journalists do not agree with PTI’s complaints that the Sindh government created problems for the organizers of the public meeting. The PPP too is confident that the PTI cannot hurt its popularity with the help of what they call ‘traditional turncoats’. “PTI’s gathering in Larkana was a failure,” according to Sharjeel Memon, a key PPP leader and the provincial information minister. “PTI cannot misguide Sindhis with propaganda and forged, abusive allegations against other politicians.” He said it was not the first time political forces had united against his party in Sindh, but the people of the province had always voted for the PPP.

Many political observers agree with him. They believe it would be very difficult for the PTI to dent the popularity of the PPP despite their failures.

Hafeez Chachar, a veteran journalist and researcher, believes the PPP knows the Sindhi people in a way other political parties and alliances do not. “In the last elections, a ten-party alliance was formed against the PPP with the support of Sindhi nationalists, but it could not hurt the PPP.”