The blasphemy law to ‘safeguard religious sentiments’ is as old as the idea of organised religion. The act of killing people for ‘blasphemous’ or ‘treasonous’ expressions predates religion, since outlawing dissent has always been pivotal in maintaining the status quo of totalitarian regimes. And so it is a no-brainer that the blasphemy law was incorporated into religious jurisprudence to conserve the hegemony of religions in authoritarian theocracies (the use of the adjective ‘authoritarian’ being superfluous here).

Verses from the scriptures of all three Abrahamic religions, when taken literally, provide credence to capital punishment for blasphemy. History also backs the claim that religious leaders have wholeheartedly endorsed the blasphemy law. Basically, as long as the clergy has had political clout, the blasphemy law has always been an integral part of the religious jurisprudence of the Abrahamic religions.

As things stand, in the year 2014, a significant number of followers of only one religion propagate the death penalty for blasphemy. According to last year’s Pew survey around 75-80% of the Muslim world wants to implement Sharia law, with the majority endorsing the primitive punishments of stoning adulterers and killing apostates.

The punishment for blasphemy in the Old Testament (Leviticus): “Anyone who blasphemes God’s name must be stoned to death by the whole community of (believers)”

And yet one doesn’t see Jews or Christians stoning blasphemers or apostates. It’s only Muslim countries doing so, citing the Sunnah and ahadith which have been used to incorporate the punishments in the Sharia law.

[quote]Pakistan is one of 13 countries - all of them being Muslim majority -where apostasy or atheism is punishable by death[/quote]

Pakistan is one of 13 countries – all of them being Muslim majority –where apostasy or atheism is punishable by death. Article 295-C of the Pakistan Penal Code also sanctions death for blaspheming against Islam. Although none of the 1,274 people accused of blasphemy between 1986 and 2013 was officially executed, 51 of them were murdered during their trial. The rest had to go into hiding or fled the country.

Even though the allegation of blasphemy is never out of the news in our neck of the woods, it has been hogging the headlines over the past couple of weeks.

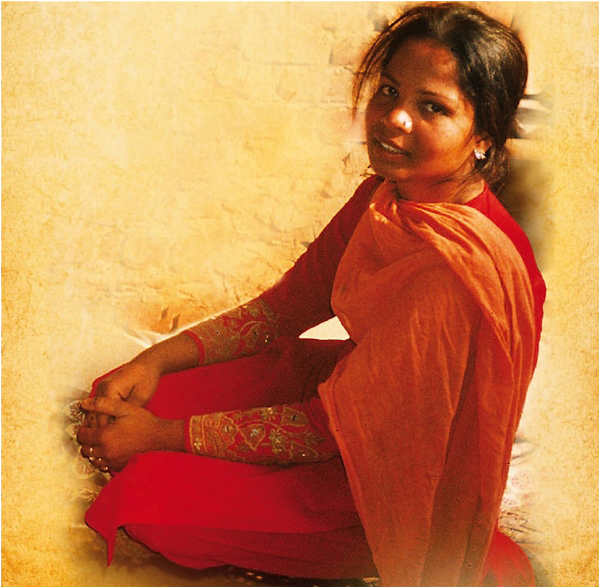

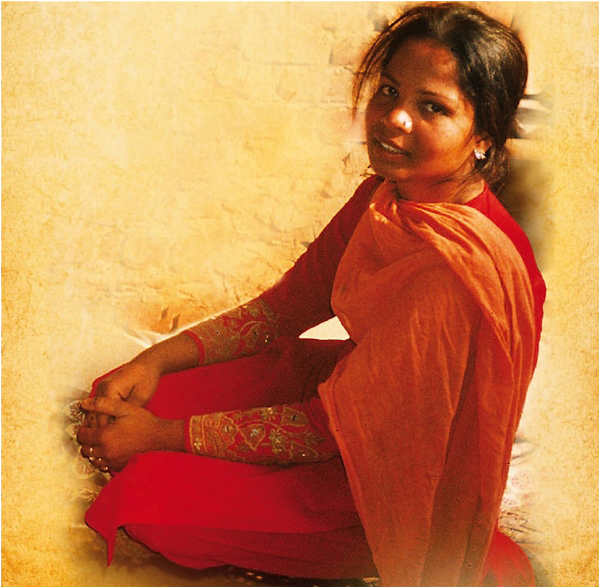

Asia Bibi, whose case is the most prominent manifestation of the misuse of Pakistan’s blasphemy law to settle personal scores against religious minorities, has been sentenced to death. Almost simultaneously, an ostensibly secular political party, MQM has accused opposition leader Khurshid Shah of blasphemy for stating that ‘mohajir’ – a word used in the Quran – is a derogatory term.

It’s ironic that a party that claims to be a torchbearer of secularism has demonstrated perfectly the blasphemy culture in Pakistan and the demerits of the law, taking a leaf out of Mubashir Luqman and ARY’s book. But then again Pakistani politicians with an apparently secular outlook have had flings with blasphemy, religious separatism and excommunications in the past.

While there are fewer weapons deadlier than a blasphemy accusation, the irony that a law designed to shield religion against ridicule makes it appear exceedingly ridiculous, seems to be lost on all proponents of the blasphemy law. That the law outlaws its own criticism is another paradoxical corollary of its self-defeating raison d’etre.

Centuries ago the blasphemy law might have been an important deterrent to coerce people into ‘respecting’ ideologies, in the 21st century all kinds of coercions are the butt of global disrespect. And the proponents of the blasphemy law also seem to be oblivious of the simple reality that silencing religious scepticism could never have been about ensuring the ‘respect’ of any god, prophet or scripture. An omnipotent deity, and the divine being’s chosen ones, would never need to chop off heads that refuse to bow down to orders.

The blasphemy law, in its goriest form, always was and still is a tool to reaffirm a religion’s political dominance. This is precisely why despite 29% of the countries in the world – including European counties like Germany and Italy – criminalising blasphemy, it’s only the countries that have incorporated religious law in their constitution that have extreme punishments. Because a law that condemns blasphemy on paper, despite contradicting the fundamentals of freedom of speech can ensure harmony by being triggered in extreme cases, but the threat of the religious guillotine ascertains reluctant subservience under the garb of veneration.

Another paradox in the Muslim world’s blasphemy law is that unlike the law in the rest of the world, it applies solely, or primarily, to Islam.

The origins of Pakistan’s blasphemy law, Article 295 of the Pakistan Penal Code and its sub-clause 295-A, are borrowed from the Indian Penal Code authored by Lord Macaulay. The original Article 295 from 1860’s Indian Penal Code, and 295-A which was incorporated later, both cater to safeguarding all worship places and religions. The sub-clauses 295-B and 295-C, added by Ziaul Haq in the 1980s are Islam-specific, and have in turn made the blasphemy law irrevocable.

Pakistan’s blasphemy law, much like most of the Muslim world, focuses solely on ensuring Islam’s respect, leaving all other religions vulnerable to constant bile. If the law were equally sensitive about the respect of all religions, most sources of entertainment, television shows, literature, curricula, and most notably the Friday sermons in Pakistan would be the first to be outlawed for the hatred against other religions, most notably Judaism and Hinduism.

In fact Article 295-C of the Pakistan Penal Code and Ordinance XX that bars Ahmadis from “posing” as Muslims, or even using Islamic titles, quite clearly contradict Article 295-A, which forbids “outraging religious sentiments.” The Second Amendment to the Pakistani Constitution “outraged the religious sentiments” of the Ahmadis by excommunicating them in 1974.

Therefore, ironically, and paradoxically, the Constitution and the Pakistan Penal Code are blasphemous according to Article 295-A of the same penal code.

Until the blasphemy law in Pakistan is revamped to shield all religions and ideologies, including that of the ‘heretics’, its skewed respect for Islam and Islam alone, would continue to be one of the greatest sources of the defamation for the religion that it vies to glorify.

Nothing has caused more disrespect to Islam than the antediluvian jurisprudence of Sharia, which is spearheaded by the blasphemy law. Because it’s the same accusations of apostasy and blasphemy that Islamist terrorist organisations like the TTP, Isis, al-Qaeda and Boko Haram use for their butchery. As long as the majority of the Muslim world continues to cling on to primitive jurisprudence, any ‘respect’ earned through these suppressive tools would be paradoxical and superficial.

Verses from the scriptures of all three Abrahamic religions, when taken literally, provide credence to capital punishment for blasphemy. History also backs the claim that religious leaders have wholeheartedly endorsed the blasphemy law. Basically, as long as the clergy has had political clout, the blasphemy law has always been an integral part of the religious jurisprudence of the Abrahamic religions.

As things stand, in the year 2014, a significant number of followers of only one religion propagate the death penalty for blasphemy. According to last year’s Pew survey around 75-80% of the Muslim world wants to implement Sharia law, with the majority endorsing the primitive punishments of stoning adulterers and killing apostates.

The punishment for blasphemy in the Old Testament (Leviticus): “Anyone who blasphemes God’s name must be stoned to death by the whole community of (believers)”

And yet one doesn’t see Jews or Christians stoning blasphemers or apostates. It’s only Muslim countries doing so, citing the Sunnah and ahadith which have been used to incorporate the punishments in the Sharia law.

[quote]Pakistan is one of 13 countries - all of them being Muslim majority -where apostasy or atheism is punishable by death[/quote]

Pakistan is one of 13 countries – all of them being Muslim majority –where apostasy or atheism is punishable by death. Article 295-C of the Pakistan Penal Code also sanctions death for blaspheming against Islam. Although none of the 1,274 people accused of blasphemy between 1986 and 2013 was officially executed, 51 of them were murdered during their trial. The rest had to go into hiding or fled the country.

Even though the allegation of blasphemy is never out of the news in our neck of the woods, it has been hogging the headlines over the past couple of weeks.

Asia Bibi, whose case is the most prominent manifestation of the misuse of Pakistan’s blasphemy law to settle personal scores against religious minorities, has been sentenced to death. Almost simultaneously, an ostensibly secular political party, MQM has accused opposition leader Khurshid Shah of blasphemy for stating that ‘mohajir’ – a word used in the Quran – is a derogatory term.

It’s ironic that a party that claims to be a torchbearer of secularism has demonstrated perfectly the blasphemy culture in Pakistan and the demerits of the law, taking a leaf out of Mubashir Luqman and ARY’s book. But then again Pakistani politicians with an apparently secular outlook have had flings with blasphemy, religious separatism and excommunications in the past.

While there are fewer weapons deadlier than a blasphemy accusation, the irony that a law designed to shield religion against ridicule makes it appear exceedingly ridiculous, seems to be lost on all proponents of the blasphemy law. That the law outlaws its own criticism is another paradoxical corollary of its self-defeating raison d’etre.

Centuries ago the blasphemy law might have been an important deterrent to coerce people into ‘respecting’ ideologies, in the 21st century all kinds of coercions are the butt of global disrespect. And the proponents of the blasphemy law also seem to be oblivious of the simple reality that silencing religious scepticism could never have been about ensuring the ‘respect’ of any god, prophet or scripture. An omnipotent deity, and the divine being’s chosen ones, would never need to chop off heads that refuse to bow down to orders.

The blasphemy law, in its goriest form, always was and still is a tool to reaffirm a religion’s political dominance. This is precisely why despite 29% of the countries in the world – including European counties like Germany and Italy – criminalising blasphemy, it’s only the countries that have incorporated religious law in their constitution that have extreme punishments. Because a law that condemns blasphemy on paper, despite contradicting the fundamentals of freedom of speech can ensure harmony by being triggered in extreme cases, but the threat of the religious guillotine ascertains reluctant subservience under the garb of veneration.

Another paradox in the Muslim world’s blasphemy law is that unlike the law in the rest of the world, it applies solely, or primarily, to Islam.

The origins of Pakistan’s blasphemy law, Article 295 of the Pakistan Penal Code and its sub-clause 295-A, are borrowed from the Indian Penal Code authored by Lord Macaulay. The original Article 295 from 1860’s Indian Penal Code, and 295-A which was incorporated later, both cater to safeguarding all worship places and religions. The sub-clauses 295-B and 295-C, added by Ziaul Haq in the 1980s are Islam-specific, and have in turn made the blasphemy law irrevocable.

Pakistan’s blasphemy law, much like most of the Muslim world, focuses solely on ensuring Islam’s respect, leaving all other religions vulnerable to constant bile. If the law were equally sensitive about the respect of all religions, most sources of entertainment, television shows, literature, curricula, and most notably the Friday sermons in Pakistan would be the first to be outlawed for the hatred against other religions, most notably Judaism and Hinduism.

In fact Article 295-C of the Pakistan Penal Code and Ordinance XX that bars Ahmadis from “posing” as Muslims, or even using Islamic titles, quite clearly contradict Article 295-A, which forbids “outraging religious sentiments.” The Second Amendment to the Pakistani Constitution “outraged the religious sentiments” of the Ahmadis by excommunicating them in 1974.

Therefore, ironically, and paradoxically, the Constitution and the Pakistan Penal Code are blasphemous according to Article 295-A of the same penal code.

Until the blasphemy law in Pakistan is revamped to shield all religions and ideologies, including that of the ‘heretics’, its skewed respect for Islam and Islam alone, would continue to be one of the greatest sources of the defamation for the religion that it vies to glorify.

Nothing has caused more disrespect to Islam than the antediluvian jurisprudence of Sharia, which is spearheaded by the blasphemy law. Because it’s the same accusations of apostasy and blasphemy that Islamist terrorist organisations like the TTP, Isis, al-Qaeda and Boko Haram use for their butchery. As long as the majority of the Muslim world continues to cling on to primitive jurisprudence, any ‘respect’ earned through these suppressive tools would be paradoxical and superficial.