I do not have an extensive library but I do have works of Fanon and many other Third World thinkers, such as Che Guevara, Paula Friere, Nyerere, CLR James, Fidel Castro and a few others. These texts have been central to my understanding of philosophy and they have also been borrowed and photo-copied on numerous occasions, in particular by students who visit my home from Balochistan, Gilgit-Baltistan or from FATA. Young intellectuals from these areas have long been enticing me to hand over the original books of Fanon.

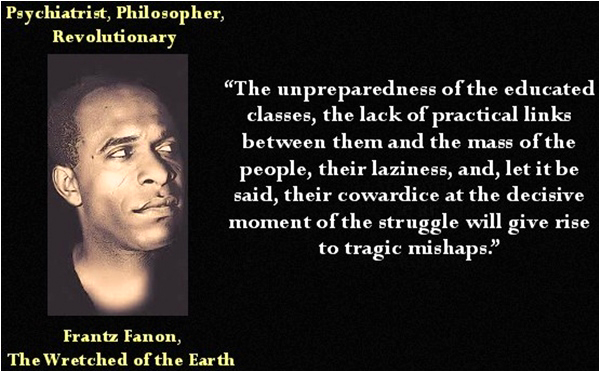

I do not have an extensive library but I do have works of Fanon and many other Third World thinkers, such as Che Guevara, Paula Friere, Nyerere, CLR James, Fidel Castro and a few others. These texts have been central to my understanding of philosophy and they have also been borrowed and photo-copied on numerous occasions, in particular by students who visit my home from Balochistan, Gilgit-Baltistan or from FATA. Young intellectuals from these areas have long been enticing me to hand over the original books of Fanon.There are three reasons that Fanon speaks to me (as a Sindhi) and to young students from Balochistan, FATA and Gilgit-Baltistan. Firstly, because his method aims to decenter the given discourses and concepts, often of colonialism, and in that sense teaches one how to critique and think from one’s situation and allow physiological discomfort (anger) to inform one’s ideas. Secondly, because his method of decentering the claims and discourse of colonialism and post-colonial states aims at decolonization. Finally, because between his actions and his ideas there is a symbiosis. He fought and died for this beliefs, which gives his texts a moral authority. In all his work he challenges practices that do not give sovereignty to the people – to those below. And colonial structures never give sovereignty to the people. It is precisely the wholesale institution or continuation of colonial practises in Balochistan, G-B, Sindh and FATA post-independence that make Fanon a comrade and ustaad for me and students from these regions.

[quote]A Sindhi hari is told that haris are poor because they are lazy and illiterate in depictions in PTV[/quote]

Fanon died when he was 36. He wrote four books, fought in the second World War having run away from home to join the allies, obtained a doctorate in psychiatry, took over and managed a psychiatry hospital in Algiers, working under the French government, and then in the final phase of his life, he resigned from the hospital and joined the Front de Liberation Nationale (FLN). For the FLN he was Ghana spokesperson and editor of their magazine El Moudjahid. He also carried out logistical and other military-related missions – although details of these are sketchy. He married and had children. There were many attempts on his life by the French government. Two stand out.

In Rome, where he went for treatment for leukemia, people entered and fired on his bed – he had been astute enough to change rooms just in time. In 1959, while on a mission on the Algerian-Moroccan border, his jeep hit a land-mine planted by the French. He survived these attempts of the colonial powers but he did not survive leukemia. He had been treated in Russia but the doctors in Russia advised him to go to Washington D.C, and so he went and there he died a month or so after arrival in December 1961. It is ironic that a leading anti-colonial fighter should die in a hospital in Washington D.C, and Fanon was well aware of the irony. In one of his last letters to one of his friends, he notes the irony but also expresses the idealism with which he led his life and that lends him a moral authority unmatched by either post-colonial leaders or intellectuals:

“What I want to say to you, Roger, is that death is always with us and that the important thing is not to know how to avoid it but to make sure we do our utmost for the ideas we believe in. The thing that shocks me as I lie here in this bed, feeling the strength exiting my body, is not that I am dying but that I’m dying of acute leukemia in Washington, D.C, when I could have died three months ago facing the enemy on a battlefield, when I already knew I had this disease. We are nothing on this earth if we do not first and foremost serve a cause, the cause of the people, the cause of freedom and justice.”

Fanon’s written work and activities challenge colonialism as a project and discourse. Colonialism can be defined as rule of a distant territory by a metropole centre. To effect a colonial project a metropole centre has to create and disseminate a discourse that makes such domination possible – justifying and motivating the colonizers and then normalizing it for the colonized, the colonizers and the world at large. In the case of European colonialism, this discourse was racial. Put simply, the closer one is to ‘whiteness’, the closer one is to being ‘human’ and the rights that it entails, and the closer one is to European culture, the closer one is to being civilized. It is clear that black persons and those of the Third World would then be furthest from being either ‘human’ or ‘civilized’. European Colonization begins in 1492 when Columbus lands in the Americas and through various modification its discourse has been on repeat up to the present.

[quote]ISIS and all attempts to return Muslim societies to an imagined past are spurred by Nativism [/quote]

As a project, European Colonialism has been gruesome and beneficial. Beneficial for Europe and America (or white America) and gruesome for the rest. In the Americas, an indigious population was reduced from 70 million to 3.5 million a century and half after European colonialism began. Another 5 million Africans died at various stages of the slave-trade as they were caught, shipped, sold and put to work at various European plantations in the Americas – not to mention the effect such a vast and brutal system had on the economic, social and political life of Africa and of the Americas. The benefits were staggering. Robin Blackburn has estimated that by 1800 the slave-based production in the Americas “had cost the slaves 2,500,000,000 hours of toil”. What the toil produced went to Europe and made possible the industrial revolution and all the grandeur we witness as tourists of Europe and America.

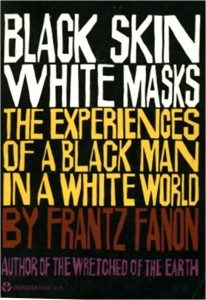

Fanon’s first book, Black Skin, White Masks, written when he was 25, demonstrates best his method of decentering colonial discourses. As a student from Martinique in France, Fanon was, as he writes, ‘over-determined from the outside’ - like all non-white persons. His skin colour, seen as black by the colonizers’ eyes, signified the binary other of whiteness, that is, it made him, to quote Fanon, ‘an animal’. If European civilization stands for whiteness and then whiteness in turn stands for that which is good, then the non-European would always come up short. Over five hundred years, the colonial discourses have embedded themselves in the European ‘collective unconscious’. They are everywhere. For example, in films, books, poems, advertising, songs, paintings and philosophy. Fanon notes that this led to a superiority complex in white people and an inferiority complex in non-white persons. Strive as the non-European might, she cannot come up to the standards of civilization (defined as they are always by whiteness) and try as a white person may to understand the ‘other’ he can never really leave the superiority that is structured not only in the ‘collective unconscious’ but also re-affirmed by material situations.

[quote]He fought and died for this beliefs, which gives his texts a moral authority[/quote]

Colonizers create which they affirm in their discourse – for example, the idea that Pakhtuns love their customs, are fierce about their independence and weapons and are ‘tribal people’, justifies the British and Pakistani imposition on them of the (barbaric) laws of the Frontier Crimes Regulations. This in turn structurally re-affirms guns, tribes and customs at the material level – books and schools or democratic practices are not allowed, which in turn re-affirms the colonial discourse on Pakhtuns. Given that a tribal system is seen as inferior to a civilized system of modernity, how could a Punjabi not feel superior when he or she sees a Pakhtun selling glasses in a market in Lahore (I would argue that the economic poverty of Pakhtuns is also structured by coloniality and is not a historical fact). What I am illustrating in this example is that the discourse on the Pakhtun is reinforced by the material conditions created by the colonizers and not by the Pakhtun himself. This is the basis of the colonial project and discourse. It makes of the colonized, ‘objects’ without agency, both of discourse and, as the colonized do not have sovereignty, they become objects to be governed by the metropole centre. In Black Skin, White Masks, Fanon is concerned with the psychological effect of coloniality and he notes that the colonized is,’‘skilfully injected with fear, inferiority complexes, trepidation, servility, despair, abasement’. What option does the colonized subject then have? Fanon notes two options, that of nativism and that of re-creation in battle.

Nativism would to be an attempt to posit a counter value system from a pre-colonial past. Gandhi, would be a nativist. His desire to return India to a pre-colonial idyllic – with all his symbols and performance of (his idiosyncratic) Hinduism - illustrate the problems that Fanon felt with the nativist option. Nativism is not possible according to Fanon, because colonialism has been too totalizing a project – it had erased or re-written sources of the pre-colonial societies and ruptured their economic, political and social bases. In the case of Americas it has been genocidal and wiped out almost completely the pre-colonial nations of the Americas. The colonized subject can find no authentic way back. Likewise, nativism, for Fanon, fails to advance humanity. Fixing, again as it does the subject in a project that is outside of her – a past imagined by leaders for her (think here of ISIS and all attempts to return Muslim societies to an imagined past – that past, then, fixes one’s present and can only be held in that fossilized position by violence, which repeats again the colonial situation rather then liberating one from it). Fanon notes in, Black Skin, White Masks, ‘the body of history does not determine a single one of my actions’, and, ‘I will not make myself the man of any past. I do not want to exalt the past at the expense of my present and my future’. Finally, nativism fails to note the advances made for all, even during colonialism. He does not reject the other side of colonialism – notably, the Enlightenment (though, he does not see it in bloated terms either for he constantly notes its underside – colonialism). Fanon then champions recreation in and through struggle.

Recreation begins in the struggle of understanding the colonial situation – or any situation of oppression. In Black Skin, White Masks, Fanon outlines a method for the oppressed for such an understanding. The method relies on the body. Here, Fanon, is in affinity with Nietzsche. From physiological discomfort values can be born. He concludes, Black Skin, White Masks, with the following prayer:

My Final Prayer:

O my body, make me always a man who questions

The oppressed, Fanon is suggesting here, have to trust their instincts. They have to trust how they feel. This sounds rather simple but it is pre-requisite for decolonial politics. If colonialization operates a totalizing discourse that finds its way into TV, books, movies, and other cultural and intellectual productions and if that is then reinforced by the creation of material conditions that reflect back on to the discourse then the only space where the colonized can find themselves is in those quiet feelings of discomfort. They have to theorize that – for everywhere else they are told lies and they see these lies reinforced in the material conditions that surround them. Let me illustrate this again with an example. A Sindhi hari is told that haris are poor because they are lazy and illiterate in depictions on PTV. When the hari looks around at other hari’s he sees them lounging around and he also notes his own illiterate state. The discourse and material conditions are reinforcing themselves. Yet, sometimes – when he sees the landlord’s Rolex or stupidity displayed in matters of agriculture - he has a feeling that the system was built this way – that if he had land and capital he would work hard and that, in fact, it is the labour of hari’s that makes land productive and not the capital of the landlord. It is these moments of bodily discomfort – or even explosions or resentment – that Fanon wants the colonized to trust and theorize. He asks us to understand and analyse the system from our position in it. By doing so we create our own understanding of our world, and in so doing, we decenter the discourse of the colonizer or the post-independence colonizers. It is precisely because Sindhis, Baloch, those from FATA and Gilgit-Baltistan find themselves only in negativity in the collective discourse of Pakistan that they find themselves in affinity with Fanon. Some of the common discourses include, the lazy Sindhi or the womanising wadera of songs and drama, the violent Pakhtun, the greedy oppressive anti-state Baloch sardar – it ought to be noted here that out of the thirty-plus Baloch sardars, only four sardars have taken up a politics for Baloch rights and only Khair Bux Marri has been consistent in that position.

This method of analysis is the first stage of what I have called Fanon’s decolonial project. It is the stage of understanding. The second stage calls for us to transcend the explosion and analysis into something positive and universal. He asks us to act. Fanon puts it best, ‘to education man to be actional, preserving in all his relations his respect for the basic values that constitute a human world, is the prime task of him who, having taken thought, prepares to act’. It is this second stage, of the ‘act’ of decolonization to which Fanon devoted the rest of his life. He did so in the belief that only when we have decolonized can we have genuine interaction between people. In this sense Fanon is in close affinity to the fakir poets of South Asia. Like Sachal Sarmast and Bulleh Shah, his politics are geared towards eradicating barriers to love. Fanon asks us to create a world where genuine interaction and love are possible.

Qalandar Bux Memon is an Assistant Professor in the Politics Department at Foreman Christian College. He is a member of a collective that organise Cafe Bol, an intellectual cafe in Lahore. They hold an annual Franz Fanon Memorial Event. This year’s event, on 30th October, will be presided over by the philosopher Gayatri Spivak. He tweets at Qalandar_