Be it the national assembly or the court of Parvez

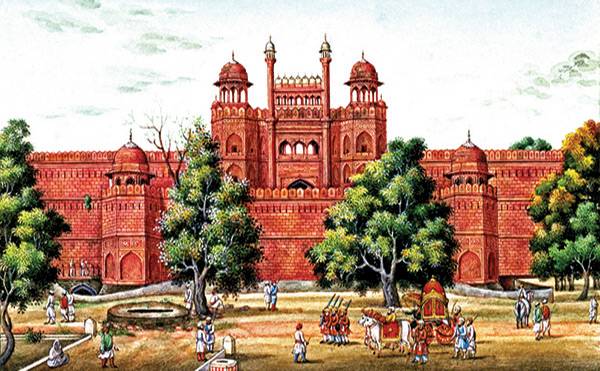

He is king who has his eye on the wealth of the other

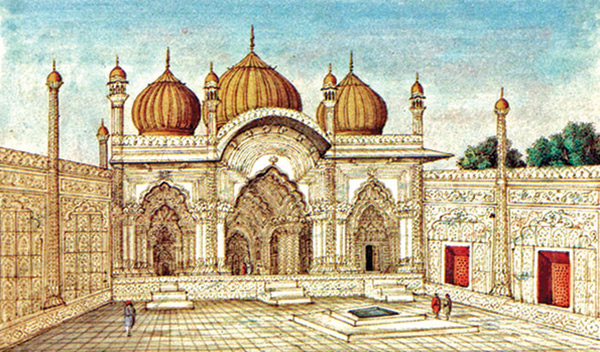

One of the great spectacles of early nineteenth century Delhi was the daily afternoon parade of the British Resident, Major General Sir David Ochterlony, and his thirteen wives, each one seated on a howdah (elephant throne) travelling on the back of a personal elephant. The procession started a little after Namaz E Asar (afternoon prayer), and followed a path along the promenade around the Laal Qilla (Red Fort) and ended at the Hawa Khana (Air Chamber) where the party camped for a while. The ‘magic hour,’ when hot Delhi air is said to turn cool, was spent at the Hawa Khana. The procession turned back after the Muslims in the entourage offered the Namaz E Maghrab (evening prayer) at the Moti Masjid (Pearl Mosque) in the fort.

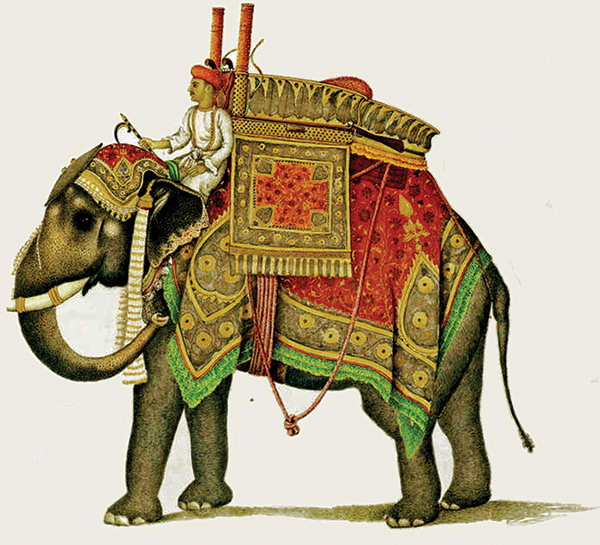

The procession was led by Octhetrlony. His howdah was, by intent, the most splendid, designed expressly for an extravagant display of pomp, grandeur and ceremony. It was made of wood and painted in silver. The design motifs were gilded and borrowed from both British and Mughal traditions. The howdah was flanked on either side by the symbol of a lion and sun carved in repousse in gold. The symbol was influenced by ancient Persian motifs of Shia Islam and employed to please his youngest, and most favoured, wife who was a Shia Muslim. The lion represented strength and the sun regal glory. A number of heraldry and floral forms were used to decorate the howdah. The howdah had two compartments. The more spacious and comfortable front compartment was used by Sir David and the one in the back was reserved for a confidante and bodyguard who, for a long time, was a eunuch gifted to him by the Raja of Jaipur. The seats were heavily padded and upholstered with chennile embroidered with gold thread.

[quote]The tasht was filled with rose petals and water in which Ochterlony soaked his feet. The servants took turns to sip water from this tray[/quote]

Four mahawats (elephant attendants) took care of the resident’s elephant. They started preparing the elephant for the afternoon ride at the crack of dawn each day. The first step was to bathe the animal and cover its back, from the shoulder to the hips, with a thick quilted pad to prevent sores caused by friction. The elephant was then painted by the mahawats, the best of whom were known for their skills as artists in addition to their expertise in taking care of elephants. The protective pad was covered with a large sheet of burgundy chennile which was embroidered with the Emperor’s coat of arms on the sides. The next layer was that of thick red silk which was embroidered with the Mughal title, Nas’r Ud Daulah (Defender of Faith), conferred to the resident by the eighteenth Mughal emperor Shah Alam Ali Gauhar. The howdah was mounted on the elephant using six folds of carefully tightened thick cotton rope.

David Ochterlony was followed by his thirteen wives seated in howdahs on elephants caparisoned with saffron head cloths embroidered in ganga jumani zardozi (silver and gold embroidery with metallic thread) style. Each had motifs of their own choice – fish, winged females, horses, khamsa (Hand of Fatimah), flowers and stars – embroidered on the sheets covering the backs of the elephants. Two mahawats were assigned to the elephants of each wife. The daily procession served its intended purpose of making a spectacular display of power, ceremony and glory.

Property of Mubarik Begum

A consummate diplomat and capable officer, Sir David had a pathologically deep love for displays of royal grandeur. Everything else was secondary. He had arrived in India as a cadet at the age of nineteen and, almost immediately, fallen in love with the country, its culture and its history. While most other officers of the Raj were singularly focused on looting the country to add to the immense wealth of the British Empire, and to make themselves rich, David Ochterlony was more interested in becoming a member of Indian royalty than in plunder and theft. The life of a Mughal emperor was the one he wanted to lead and vowed never to return to England. When asked why he wanted to live forever in India, he replied by asking a question with an almost innocent incredulity, “Where else could I live like a king?”

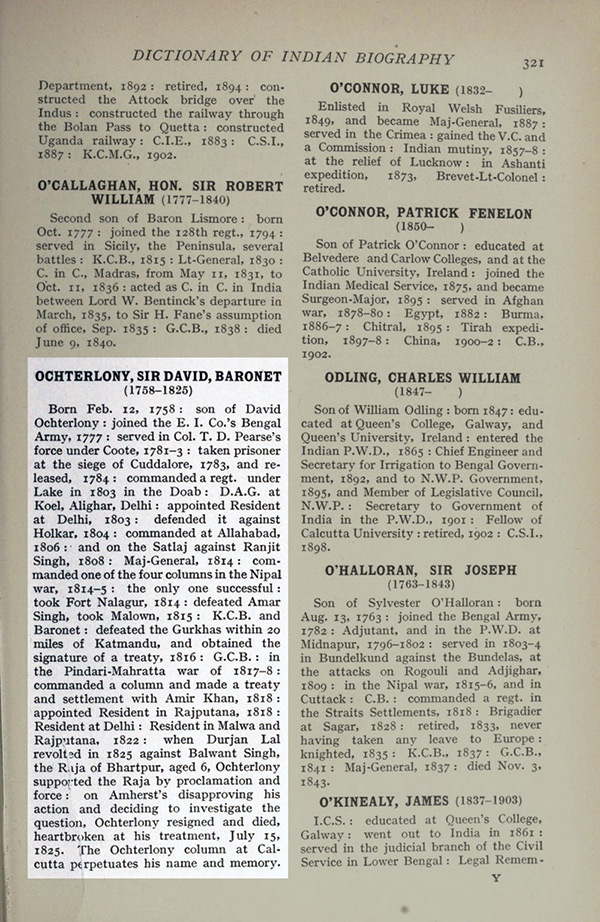

David Ochterlony was born to Katherine Tylor and Captain David Ochterlony in Boston in 1758. His father passed away when David was a child. The death of the senior Ochterlony left the family insolvent and in considerable danger, forcing them to flee first to Canada and then to England at the beginning of the American Revolution in 1765. Katherine married Sir Isaac Heard, an officer at the College of Arms, in London. Sir Isaac developed a close personal relationship, both as a father and as a friend, with David Ochterlony and remained his most trusted confidante until his death in 1822. In 1777, David Ochterlony joined the British army, with the help of Sir Isaac, and came to India as a cadet.

In India, Ochterlony rose through the military ranks at a remarkably fast pace. He was promoted to Lieutenant in 1778 and Lieutenant Colonel in 1803. He became the British Resident at Delhi the same year and held the post for three years, getting promoted to Deputy Adjutant-General in the Battle of Delhi during the Second Anglo-Maratha War. He was made Colonel in 1812 and Major General in 1814. During the Gurkha War, he was given the command of one of the four columns in which Lord Moira Hastings had divided his forces. Due to his remarkable performance as commander in the war, he was made a Knight of the Bath in 1815 and, a few months later, advanced to Knight Grand Cross, making him the first British army officer in India to receive the honor. After he forged a political solution to end the Pendhari War, without a military engagement, Lord Moira Hastings reinstated Ochterlony as British Resident at Delhi in 1818. As resident, he lived an unabashedly lavish lifestyle, his extravagant and lavish ways attracting both scorn and respect, and becoming the subject of much discussion, ridicule and gossip. He came to known as Kamal Akhtar Loony. Kamal (Excellence) and Akhtar (Star) being popular Indian names and loony referring to how a lot of people saw the resident’s behavior. Akhtar Loony was a corruption of the resident’s last name that locals found easy to pronounce. The sobriquet caught on throughout the region; Ochterlony, however, preferred to be addressed by his Mughal title, Nas’r Ud Daulah, which he loved so much that he had it inscribed in jade on his administrative seal.

David Ochterlony led a double life. One in which he was an astute politician, a capable army officer and a skillful diplomat and the other more personal life that he led as an Indian emperor. The cavalcade of fourteen elephants belonged to the life that was nearer and dearer to his heart.

[quote]She counted the great Mirza Asadullah Khan Ghalib and Sheikh Muhammad Ibrahim Zauq amongst her personal friends[/quote]

The procession was followed by an elaborate Charan Amrit ceremony which was managed by the thirteenth, and most favored, wife of the Major General, Bibi Mah Ratan Mubarakunissa Begum. Servants of the household were required to participate in the ceremony. A large shallow tray with raised edges, known as tasht, made of silver with brass inlay using the Bidri technique was used for Charan Amrit. The tasht was filled with rose petals and water in which Ochterlony soaked his feet. The servants took turns to sip water from the tray in a highly submissive gesture signifying both loyalty and devotion.

The Charan Amrit was not the only thing managed by Mubarak Begum. The resident’s youngest wife was an ambitious woman who thrived on power and control. She was said to be the mistress “of everyone within the walls” of the Ochterlony household. Originally, a Hindu Brahmin slave girl named Champa, who made her living as a prostitute and dancing girl, Sir David had purchased her as a concubine while she was a teenager. He married her after she converted to Islam a few years later. Mubarak Begum bore him his youngest children - two girls – and helped raise a Muslim girl that had been adopted. Mubarak Begum was known to have used her storied skills as a love-maker to gain complete control over her significantly older husband. She was one of the most powerful women in Delhi in the nineteenth century. Mubarak Begum came to be known as Jarnaili Begum due to her influence, power and clout. An observer remarked that “making Sir David the Commissioner of Delhi was the same as making Jarnaili Begum [the commissioner].” The Nas’r Ud Daulah would hold court together with Mubarak Begum who made it a habit to offer and receive nazar (gifts) and khilats (robes of honor) in the manner of the royals. The Begum referred to herself variously as Lady Ochterlony and Qudsia Begum (the Pious One), a name used by the mother of the penultimate Mughal emperor, Akbar Shah II.

Lady Ochterlony managed one of the largest retinue of servants in the households of British officers in India. A large horde of servants in the homes of Englishmen was a norm and, to some extent, a necessity in India. Each servant was able to perform only certain specific duties as prescribed by rigid caste rules and religious statutes. As a result, the average number of servants in the British household in nineteenth century India was sixty. The Ochterlony family of twenty-one – the Resident, thirteen wives, six natural children and one adopted child – employed more than four hundred servants. The battery of hired help included aayahs (nannies), bahishtis (water bearers), chobdars (drovers), chowkidars (watchmen), darzis (tailors), dhobis (washermen), hajaams (barbers), harkaras (messengers), huqqah bardars (hubble carriers), jamadars (janitors), kahars (palanquin bearers), khansamas (chefs), khidmatgars (table boys), maasis (maidservants), mahawats, malis (gardeners), mashalchis (lamp bearers), munshis (Indian languages teachers), piyadas (peons), qulis (porters), saar baans (camel drivers), sirdars (valets), syce (groom), and a number of others. Mubarak Begum’s strict management of the large number of servants was the talk of the town in Delhi and the subject of many stories.

Mubarak Begum was a highly skilled dancer and singer and considered to an authority on the art of lovemaking. The resident was said to have slept with none of his other twelve wives after marrying Mubarak Begum. The begum introduced the habit of taking daily baths to her husband who, like others from his country, paid little attention to personal hygiene. Although a convert to Islam, the formidable young lady was a devout Muslim who observed Ramzan, Muharram, Eid Al Fitr, Eid Al Azha, Eid Mailad Un Nabi and other Muslim festivals and commemorations with a studied and conspicuous fervor. Urdu and Persian poetry was Mubarak Begum’s greatest love among the arts. She counted the great Mirza Asadullah Khan Ghalib and Sheikh Muhammad Ibrahim Zauq amongst her personal friends and was a regular participant in the famed mushairas (poetry recitation symposiums) held in the courtyard of the Delhi College (now Zakir Husain Delhi College) outside the Ajmeri Gate. She gave her adopted daughter’s hand in marriage to Ghalib’s nephew, Arif Khan. Mirza Farhatullah Beg’s fictional account of the last great mushaira in Mughal Delhi, Dilli Ki Akhri Shama , was set in Mubarak Begum’s home.

[quote]She indulged every one of his many idiosyncrasies with an irrational level of devotion[/quote]

And while Mubarak Begum enjoyed the many trappings of power, and the arts, her life revolved around Sir David Ochterlony. She indulged every one of his many idiosyncrasies with an irrational level of devotion and made her husband’s romantic vision of leading the life of a Mughal emperor real for him. The Begum commissioned a portrait of her husband on ivory that she had set in gold in European style. The locket was worn by her at all times to please her husband and demonstrate her favored position amongst his many wives.

Sir David had an extraordinary love for ittar, the Indian perfume oil made from natural sources without any alcohol. Guests to the Ochterlony home were always offered a gift of ittar in a glass bottle at the time of their departure. Amber, Mushk Al Madina, Zaafraan, Shamama, and Oud ittars, which are said to have a warming effect on the body, were given as gifts during the winters, and Khus, Gulab, Kewra, Mogra, Motia and Yasmin, which have a cooling effect, were summer gifts. The very expensive and rare Oud Al Hind was Sir David’s favorite ittar; he carried it in a small crystal bottle decorated with rubies and emeralds set in gold. The bottle was a gift from Akbar Shah II and said to be a personal possession of Mughal emperor Jalal ud-din Muhammad Akbar.

[quote]The begum did not share her knowledge of adding exotic substances and secret ingredients to make the best of ittars

with anyone[/quote]

Mubarak Begum was an expert perfume maker. She had her husband’s ittar prepared at home under her own supervision. She kept a large stock of flowers, herbs, spices, roots, grasses, woods, and animal substances, to make ittar in her home. Her kitchen was equipped to handle all processes – drying, extracting, fermenting, distilling, straining and bottling – involved in the production of ittar. The begum did not share her knowledge of adding exotic substances and secret ingredients to make the best of ittars with anyone. These included falanja, the red seed of the sheetal cheeni (cubeb) plant and zar gul kanwal (lotus pollen). She added these and several other secret ingredients to the ittar during the fermentation stage, in proportions known only to her, when alone in the kitchen to safeguard her secrets.

Mubarak Begum organized highly elaborate and ostentatious musical soirées for her husband at their home. Her goal was to produce the awe, amazement and admiration that her husband craved while maintaining the dignity and decorum of Indian mehfils of music. The parties were held regularly in the large atrium of the Ochterlony haveli in Delhi, throughout the year.

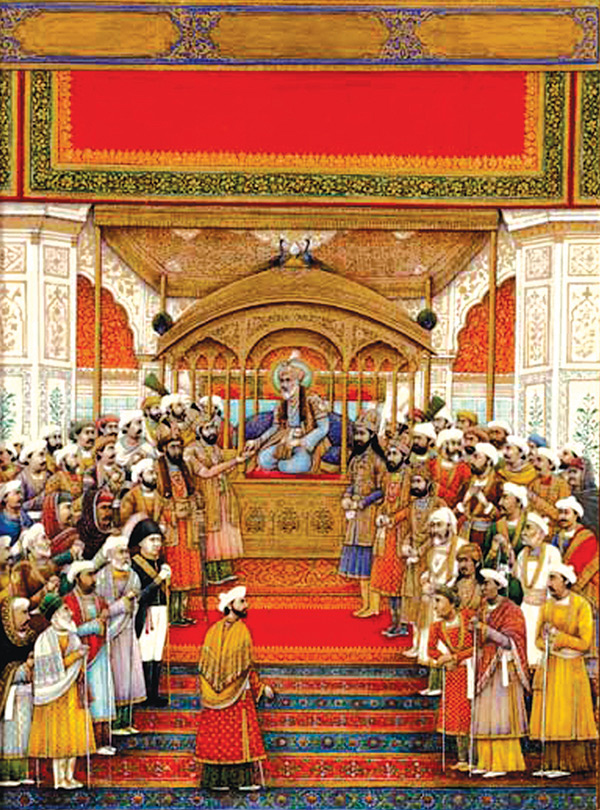

Sir David Ochterlony occupied the central place of importance in the soirées, seated conspicuously on a diwan (rectangular ottoman) in full Mughal regalia in the middle of the atrium. Sir David liked seedha pajamas (straight-cut drawstring trousers) made of zarbaft kemkhab (brocade made with gold thread) which was lined with malmal (muslin) for comfort. He wore lightly embroidered kalidaar kurtas (paneled tunics) with extravagantly embroidered jamahs (robes). The jamahs were typically made of malmal and covered with a repeating booti (small floral motif) pattern embroidered with zari (gold thread). The neckline was covered with intricate zardozi embroidery and the hemlines had gold gota sinjaf (metallic ribbon facing) that showed through the hems of the garment. A jamdani patka (woven sash) was tied around the waist to complete the formal ensemble. Sir David crowned himself with a pagri (turban) tied from a twenty-one foot length of fine silk and emblazoned with a Mughal kundan sarpech (aigrette made of gold and foil-lined gems).

Sir David always sat alone amidst a spread of pillows and cushions on the diwan (rectangular ottoman), smoking a long-hosed hookah. He personally selected the hookah for each mehfil from his vast collection of more than one hundred hubbles with glass, bidri and jade bases. Two servants stood on each side with morchals (fly whisks) and two behind the diwan waving pankhas (fans) made of white peacock feathers. The women of the household watched performances from behind chilmans (portières) whereas Mubarak Begum sat on a smaller diwan to the right of her husband. The guests – invariably males – sat on chandanis (white cloth sheets) laid on top of cotton padding and carpets. Brightly polished brass hookahs, freshly prepared and regularly refreshed by hookah bardars, were placed in front of the guests. The whole pavilion was decorated with fanoos (chandeliers), shamadans (lamps), qandeels (lanterns), chehal chiragh (candelabra) and mashals (torches) creating a profusion of light in different colors and hues. The atrium was decorated with garlands of roses and jasmine. Guests were given gajras (bracelets made of flowers) as they arrived, while servants sprayed rosewater on them, and elsewhere, using gulab paashes (rosewater sprinklers). The fragrance of kastoori (musk), sandal (sandalwood), yasmin and motia filled the area. Servants served misri (crystallized sugar), mithai (sweets), supari (areca nut) and sharbat (sweet drink) throughout the night while guests passed around paan (betel) in silver khaasdaans (serving dishes for paan). Peekdaans (spittoons) were placed in every nook and corner of the courtyard to ensure cleanliness. Munshis and writers are said to have refused to document the events, confessing their inability to put in words what was an indescribably festive atmosphere.

The Ochterlony soirées centered on nautch (dance) performances by five or six dancers; vocal and instrumental music was secondary in importance and used primarily to accompany the nautch girls. Sarangi, dholak, manjeera, and tabla players performed while standing while the singers and sitar players sat on carpets during recitals. The parties ended at the call of the Namaz E Fajr (Morning Prayer).

The wildly extravagant “native” ways of Nas’r Ud Daulah inspired awe, amazement and reverence while attracting attention. A lot of attention.

[quote]Ochterlony received him while sitting on a diwan, wearing a turban and Indian clothes[/quote]

The Anglican Bishop of Calcutta, Reginald Heber of Calcutta, who met Sir David briefly in Rajputana (now Rajhastan), was shocked when Ochterlony received him while sitting on a diwan, wearing a turban and Indian clothes, while being fanned with morchals by servants. The bishop was impressed by Ochterlony’s profligate ways and grand lifestyle but lamented what he viewed to be his moral decline. “There was a considerable number of horses, elephants, palanquins and covered carriages,” wrote Heber. “Ochterlony maintains an almost kingly state. He has been absent from his home country about 54 years; he has there neither friends nor relations, and he has been for many years habituated to Eastern habits and parade.” Ochterlony’s sexual relationships were morally reprehensible in Heber’s eyes who viewed them as sins against God and a violation of a gentleman’s code of conduct. Heber’s views on Ochterlony were widely read and discussed in the English community in India.

The wife of the British Commander In Chief in India, Lady Maria Nugent took a particular exception to officers who, in her opinion, had gone native by abandoning Christianity and the English way of life. She castigated Ochterlony, publicly and privately, for having become more Muslim than Christian and more Indian than English and made no secret of her passionate hatred for Ochterlony’s lifestyle and for his person.

[quote]Sir David handled gossip, ridicule and derogatory remarks about himself with a nonchalant amusement bordering on delight[/quote]

Sir David handled gossip, ridicule and derogatory remarks about himself with a nonchalant amusement bordering on delight. Over a period of more than four decades, he had finessed the art of handling disparagement, vilification, scorn and derision as much as he had learned to enjoy respect, reverence, awe, envy and glorification.

What he had not prepared himself for was public coddemnation and humiliation by the most powerful in the British Raj. Ochterlony fell out of favor when Lord Moira Hastings left India and was succeeded by Lord William Pitt Amherst as the Governor General of India. The Governor General used succession issues in Bharatpur to engineer a public embarrassment for Major General Sir David Ochterlony that left him no choice but to resign and return to Delhi. The deliberately public censure hurt Ochterlony’s spirit and health, forcing him to spend the last few years of his life in a profound state of depression and sadness.

[quote]Kamal Akhtar Loony was not buried in the glorious tomb he had built for himself[/quote]

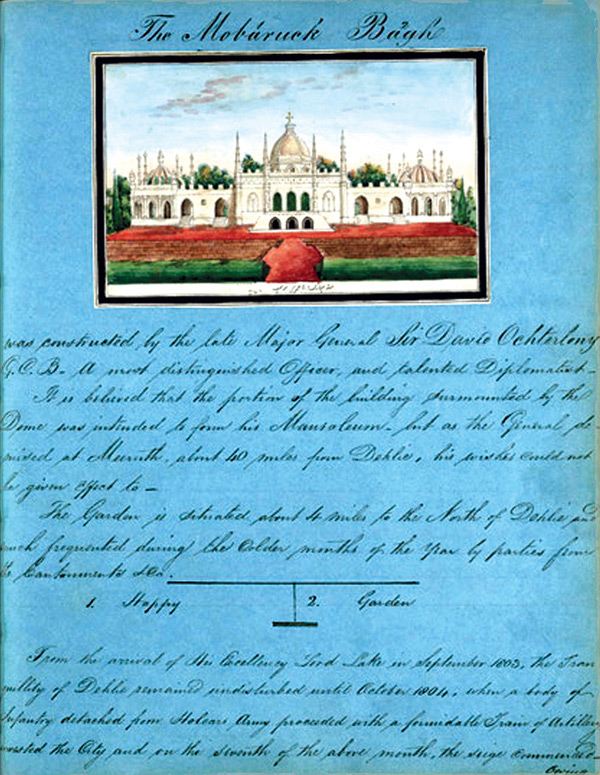

In retirement, Ochterlony began to construct an extraordinary tomb for himself and Mubarak Begum in Mubarak Baagh, the Mughal garden that he had built for his beloved young wife. The central dome of the tomb was designed like the St. James Church in Delhi and surrounded by a forest of minarets, cupolas and domes built in Islamic style. Designed as an architectural expression of the fusion of Christianity and Islam, and of England and India, this was to be the last of the great Mughal garden-tombs, built, this one time, by an Englishman and not a Mughal. A few months after tendering his resignation, Sir David died in Meerut after a brief illness. His funeral was a small and simple affair. Kamal Akhtar Loony was not buried in the glorious tomb he had built for himself. The magnificent structure, built in the tradition of the Taj Mahal and Humayun’s tomb, remained empty for more than three decades before being destroyed by British forces in the mutiny of 1857.

[quote]No one wanted to visit, what came to be known as and is still referred to as, Randi Ki Masjid[/quote]

After the death of her husband, Mubarak Begum was shunned by both the British and the Indians. The begum used her considerable inheritance to build herself a huge haveli and a mosque near Hauz Qazi in Chandani Chowk but failed to gain acceptance in Delhi society. The British and the Indians treated her with a passionate hatred; her pomposity, arrogance and haughtiness, tolerated for years as the wife of the resident, became her undoing. Her husband’s death took all her titles away overnight and reduced her to the social status of a nautch girl and prostitute. Masjid Mubarak Begum failed to attract the faithful; the marble floored prayer chamber always remained dark and cold, the irregular call for prayer from its red and green domes always muffled. No one wanted to visit, what came to be known as and is still referred to as, Randi Ki Masjid (the Harlot’s Mosque).

Dejected and despondent, Mubarak Begum married a Mughal officer name Vilayat Ali Khan and fought against the British in 1857. After the war, her entire property including the garden and mosque built in her name was confiscated by the British. Champa died alone and in dire poverty.

Ally Adnan lives in Dallas, Texas, where he works in the field of mobile telecommunications and writes about culture and art. He can be reached at allyadnan@outlook.com