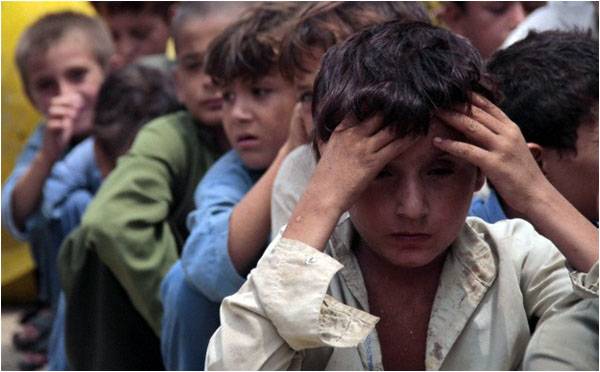

Imagine standing in a line, in the blistering heat with temperatures soaring up to 45 degrees Celsius, with no shelter, no relief, in the middle of the fasting month of Ramzan, to be able to register with your authentic NADRA card, because without it, you will not get the SIM card that allows you access to the relief money, or the rations so you can feed your family. Imagine standing in that line, sweating, dehydrated, exhausted, but unable to even sit for a moment as the line crawls forward, for hours upon hours, having travelled for up to 40 kilometers on foot, clutching on to your ID card, because it, quite literally is your lifeline. Imagine that you finally make it to the front of the queue, and then someone points out to you the queue for the food, the queue for the camps, and the queue for the payment of relief money from the federal, KPK and Punjab governments.

As of July 18, 2014, 876,999 individuals have been accounted for at the registration points established in Bannu by the Provincial Disaster Management Authority (PMDA). That is a staggering number of IDPs, but it is not the first such crisis we have had to manage. A near identical situation arose in May 2009, when Operation Rah-e-Raast was launched in the Swat Valley, resulting in over 2.9 million IDPs over time. The number above is a fraction of that, and likely bloated, as the number registered actually far exceeds the estimated population of the affected areas, and that this number will likely go down as double registrations from the same family are highly probably, and will be vetted out over time.

At the start of this conflict, despite political mudslinging between the federal and provincial governments, it seemed that certain hard-learned lessons from prior campaigns had left their mark. Rations were plentiful, fully equipped camps were established, registration points were established efficiently and effectively. Over time, the situation evolve, and so did the response. Additional registration points were opened, even in Peshawar, to allow IDPs to access the relief provided, military hospitals were established, ample food continued to stockpile to ensure no one went hungry. But as this conflict goes on, and the daily “kill sheets” are shared by the military, mismanagement has began rearing its ugly head, cross-cutting across a wide range of parameters.

[quote]This situation could be managed better than it is right now, but it is also being managed better than it was in 2009[/quote]

In mid-July, IDPs complained of terrible living conditions in camps, inadequate facilities, and no funds disbursement. The resulting clamor forced the governor to sack the Director General FATA Disaster Management Authority (FDMA), and appoint a new caretaker. In another fiasco, Federal Minister for the Ministry of States and Frontier Regions, Lt Gen Abdul Qadir Baloch promised 2,000 vehicles during this crisis to help evacuate the refugees. This endeavor was billed as well, but so far, not one vehicles has been used for this purpose. One of the biggest challenges remains female health and access, with hospitals and medical clinics lacking female doctors or nurses, and a recent tribal decree banning women from collecting food aid.

This situation could be managed better than it is right now, but it is also being managed better than it was in 2009. The powers that be have already announced that there is a six-month plan to rehabilitate the nearly one million people displaced by this war, which will further strain resources, invoke donor and humanitarian fatigue, and further alienate a group of people already wroth over the government’s actions.

The role of the National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA), despite what the Pakistan Tehrik-e-Insaaf (PTI) may have you believe, is to serve as a coordinating vector between various bodies since disasters are normally cross-cutting themes. Disaster management is a provincial subject, even before the 18th amendment, and thus the direct ownership of this IDP crisis belongs to PDMA, FDMA and Provincial Reconstruction, Rehabilitation & Settlement Authority (PaRRSA). However, as the coordinating body, at some point the NDMA has to take stock, and determine the gaps, the loopholes and the mismanagement that is negatively affecting the IDPs. Its role, then, is to suggest improvements in strategy, both at the structural and non-structural levels, to better manage the issue.

The author is a media and development professional, and holds a Master’s degree in strategic communications from Ithaca College, New York.

Email: zeeshan[dot]salahuddin[at]gmail[dot]com

Twitter: @zeesalahuddin

As of July 18, 2014, 876,999 individuals have been accounted for at the registration points established in Bannu by the Provincial Disaster Management Authority (PMDA). That is a staggering number of IDPs, but it is not the first such crisis we have had to manage. A near identical situation arose in May 2009, when Operation Rah-e-Raast was launched in the Swat Valley, resulting in over 2.9 million IDPs over time. The number above is a fraction of that, and likely bloated, as the number registered actually far exceeds the estimated population of the affected areas, and that this number will likely go down as double registrations from the same family are highly probably, and will be vetted out over time.

At the start of this conflict, despite political mudslinging between the federal and provincial governments, it seemed that certain hard-learned lessons from prior campaigns had left their mark. Rations were plentiful, fully equipped camps were established, registration points were established efficiently and effectively. Over time, the situation evolve, and so did the response. Additional registration points were opened, even in Peshawar, to allow IDPs to access the relief provided, military hospitals were established, ample food continued to stockpile to ensure no one went hungry. But as this conflict goes on, and the daily “kill sheets” are shared by the military, mismanagement has began rearing its ugly head, cross-cutting across a wide range of parameters.

[quote]This situation could be managed better than it is right now, but it is also being managed better than it was in 2009[/quote]

In mid-July, IDPs complained of terrible living conditions in camps, inadequate facilities, and no funds disbursement. The resulting clamor forced the governor to sack the Director General FATA Disaster Management Authority (FDMA), and appoint a new caretaker. In another fiasco, Federal Minister for the Ministry of States and Frontier Regions, Lt Gen Abdul Qadir Baloch promised 2,000 vehicles during this crisis to help evacuate the refugees. This endeavor was billed as well, but so far, not one vehicles has been used for this purpose. One of the biggest challenges remains female health and access, with hospitals and medical clinics lacking female doctors or nurses, and a recent tribal decree banning women from collecting food aid.

This situation could be managed better than it is right now, but it is also being managed better than it was in 2009. The powers that be have already announced that there is a six-month plan to rehabilitate the nearly one million people displaced by this war, which will further strain resources, invoke donor and humanitarian fatigue, and further alienate a group of people already wroth over the government’s actions.

The role of the National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA), despite what the Pakistan Tehrik-e-Insaaf (PTI) may have you believe, is to serve as a coordinating vector between various bodies since disasters are normally cross-cutting themes. Disaster management is a provincial subject, even before the 18th amendment, and thus the direct ownership of this IDP crisis belongs to PDMA, FDMA and Provincial Reconstruction, Rehabilitation & Settlement Authority (PaRRSA). However, as the coordinating body, at some point the NDMA has to take stock, and determine the gaps, the loopholes and the mismanagement that is negatively affecting the IDPs. Its role, then, is to suggest improvements in strategy, both at the structural and non-structural levels, to better manage the issue.

The author is a media and development professional, and holds a Master’s degree in strategic communications from Ithaca College, New York.

Email: zeeshan[dot]salahuddin[at]gmail[dot]com

Twitter: @zeesalahuddin