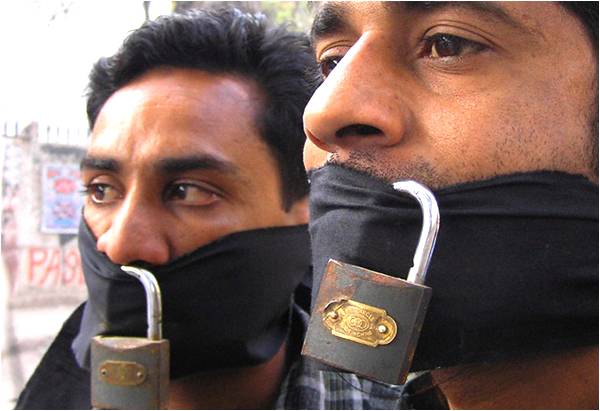

The ongoing tussle between competing power centers and a factionalized media has fueled fresh debate about free speech in Pakistan. But this debate has so far been both short in substance and lacking in any meaningful direction.

A constant and vigorous discourse on free speech is an essential hallmark of a constitutional democracy. The continuously expanding constitutional protections accorded to free speech in the United States are a direct consequence of such discourse spanning well over a century now. On the contrary, the acceptable limits on freedom of speech and expression in Pakistan are far from settled as the state and the citizenry have yet to conceptualize the meaning and purpose of free speech in a democracy in appropriate terms.

Crucially, our courts have also been unable to develop a corpus of free speech jurisprudence, and free speech cases continue to be decided more or less on a tabula rasa. Contrast this with the pioneering role of the US Supreme Court in expatiating on free speech and expanding its range.

[quote]Our courts have been unable to develop a corpus of free speech jurisprudence[/quote]

From a legal standpoint, the vaguely worded restrictions on speech and expression set forth in Article 19 of our Constitution remain indeterminate. Moreover, no clearly laid down standards or balancing tests guide our courts in the determination of the reasonableness and necessity of these restrictions. Beginning with the test case of the blanket ban on Youtube, such standards and guidelines should be judicially laid down in consonance with Pakistan’s international legal obligations under various international instruments and norms including the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR).

The true measure and value of free speech in a democracy is its indispensable contribution to the deliberative process. Beyond a facilitative legal and regulatory framework, this requires an electronic media that devotes broad and deep attention to public issues and exposes the public to a wide and diverse spectrum of opinion. It is vital for democratic health that people are able to hear sharply divergent views. Awareness of challenges to conventional wisdom from a variety of different perspectives is at least as important as knowing the conventional wisdom itself.

Lamentably, the deficiencies in our market driven electronic media are hampering our nascent democratic development at the moment. With its content and conduct controlled by a frenzied rat race for ‘ratings,’ the electronic media today mostly consists of low brow political content and sensationalized anecdotes. A large majority of its paladins lack formal professional training. It routinely turns much political discussion into cacophonous political mudslinging. It is marked by a ceaseless race to the bottom with respect to the quality and quantity of attention that it requires. Habitually drawing hasty conclusions without sufficient reasons, it almost never gets to the nub of important public issues. A reductionist version of conventional morality is its preselected prism of analysis on most issues of public importance. Underlining its systematic failure, it is almost impossible for dissenting or minority views to get a serious hearing.

An electronic media which stimulates rather than dulls the deliberative process requires an independent and transparent regulatory authority with clearly defined goals and terms of reference and vested with necessary powers to get its rulings implemented. In this context, PEMRA’s legal and administrative structure needs an urgent overhaul to ensure that it acts as a neutral and an effective body and not as a handmaiden of the executive.

Additionally, the Competition Commission of Pakistan should be empowered to prevent monopolistic practices and tendencies in the media industry. Media conglomeration is clearly at variance with the goals of free speech in a democracy as it inevitably leads to suppression of diversity of information. Concentrated media can thus never serve the public interest adequately.

Perhaps most importantly, the electronic media should regulate itself by introducing and implementing stringent editorial policies and controls which foster greater due diligence leading to more ethical and nuanced journalism. Only then might the electronic media elevate itself to the fourth pillar of our democracy and play a constructive role in its entrenchment.

The writer is a lawyer. He can be reached at as2ez@virginia.edu

A constant and vigorous discourse on free speech is an essential hallmark of a constitutional democracy. The continuously expanding constitutional protections accorded to free speech in the United States are a direct consequence of such discourse spanning well over a century now. On the contrary, the acceptable limits on freedom of speech and expression in Pakistan are far from settled as the state and the citizenry have yet to conceptualize the meaning and purpose of free speech in a democracy in appropriate terms.

Crucially, our courts have also been unable to develop a corpus of free speech jurisprudence, and free speech cases continue to be decided more or less on a tabula rasa. Contrast this with the pioneering role of the US Supreme Court in expatiating on free speech and expanding its range.

[quote]Our courts have been unable to develop a corpus of free speech jurisprudence[/quote]

From a legal standpoint, the vaguely worded restrictions on speech and expression set forth in Article 19 of our Constitution remain indeterminate. Moreover, no clearly laid down standards or balancing tests guide our courts in the determination of the reasonableness and necessity of these restrictions. Beginning with the test case of the blanket ban on Youtube, such standards and guidelines should be judicially laid down in consonance with Pakistan’s international legal obligations under various international instruments and norms including the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR).

The true measure and value of free speech in a democracy is its indispensable contribution to the deliberative process. Beyond a facilitative legal and regulatory framework, this requires an electronic media that devotes broad and deep attention to public issues and exposes the public to a wide and diverse spectrum of opinion. It is vital for democratic health that people are able to hear sharply divergent views. Awareness of challenges to conventional wisdom from a variety of different perspectives is at least as important as knowing the conventional wisdom itself.

Lamentably, the deficiencies in our market driven electronic media are hampering our nascent democratic development at the moment. With its content and conduct controlled by a frenzied rat race for ‘ratings,’ the electronic media today mostly consists of low brow political content and sensationalized anecdotes. A large majority of its paladins lack formal professional training. It routinely turns much political discussion into cacophonous political mudslinging. It is marked by a ceaseless race to the bottom with respect to the quality and quantity of attention that it requires. Habitually drawing hasty conclusions without sufficient reasons, it almost never gets to the nub of important public issues. A reductionist version of conventional morality is its preselected prism of analysis on most issues of public importance. Underlining its systematic failure, it is almost impossible for dissenting or minority views to get a serious hearing.

An electronic media which stimulates rather than dulls the deliberative process requires an independent and transparent regulatory authority with clearly defined goals and terms of reference and vested with necessary powers to get its rulings implemented. In this context, PEMRA’s legal and administrative structure needs an urgent overhaul to ensure that it acts as a neutral and an effective body and not as a handmaiden of the executive.

Additionally, the Competition Commission of Pakistan should be empowered to prevent monopolistic practices and tendencies in the media industry. Media conglomeration is clearly at variance with the goals of free speech in a democracy as it inevitably leads to suppression of diversity of information. Concentrated media can thus never serve the public interest adequately.

Perhaps most importantly, the electronic media should regulate itself by introducing and implementing stringent editorial policies and controls which foster greater due diligence leading to more ethical and nuanced journalism. Only then might the electronic media elevate itself to the fourth pillar of our democracy and play a constructive role in its entrenchment.

The writer is a lawyer. He can be reached at as2ez@virginia.edu