There is no such thing as a free lunch. As explained by the Economist Alan Beattie in his book False Economy, artificial control of cost of production and subsidy builds an entire false economy that is disconnected from the economic reality of a society. Market economy is based on the principle of a fair, efficient distribution of resources. These principles have been ignored in Pakistan’s power sector, and thus the mechanism of subsidy has continued to hurt electricity production and distribution.

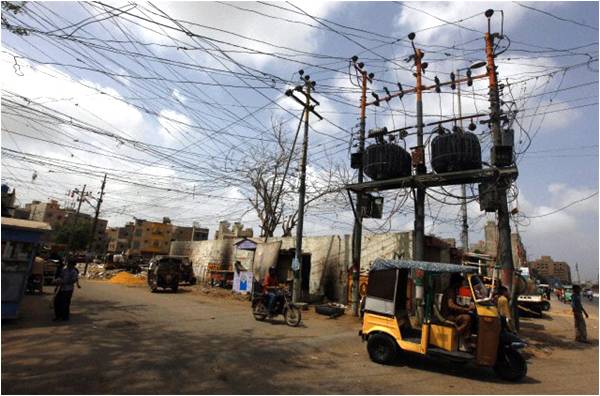

Subsidy has become a political favour to both consumers and producers. We can’t even call it a market failure, because the power sector in Pakistan is not even a perfect market. A restructure plan developed in 1992 included three stages – decentralization, corporatization and privatization. Its been more than two decades since then, and we are still on the stage of corporatization.

Perhaps that is why the IMF has included the elimination of subsidies in its recent set of rather tough loan conditions. Recently, the head of the IMF mission in Pakistan stated that the government should only allow subsidy on power to consumers who use less than 50 units of electricity – which would include people who only run a fan and a light bulb. Consumers who use 50 units or less pay Rs 2 to Rs 4 per unit. Those who use less than 100 units pay Rs 4 to Rs 8, and the rates get progressively higher based on usage. The tariff for the producers is determined by the National Electric Power Regulatory Authority, and it is much higher than what the consumer is paying. On an average, the rates range between Rs 14 to Rs 18 per unit.

[quote]Subsidy has become a political favour to producers and consumers[/quote]

The purpose of the establishment of a regulator is to encourage private investors, and to give a differential tariff and not unified rates, because that amounts to killing the spirit of decentralization. The corporatization of the power sector was expected to ensure efficient production and lesser pilferages and line losses. But the fact that the power sector needs subsidies shows that the power production and distribution companies are inefficient entities.

[quote]There is a need to attract investors in the solar industry[/quote]

The issue becomes critical when we consider that it is a forced subsidy, and not a volunteer subsidy, which is mostly associated with lifeline consumers. Since the power sector in Pakistan is still transitioning from the public to the private sector, there persists a kind of confusion. The generation and distribution companies are supposed to apply to NEPRA for a tariff review, which then redetermines the rates based on a given mechanism. This rate is notified by the government, and is applicable to all the companies and not just the ones that asked for a higher tariff. The government therefore pays a cross subsidy, not just to people who use up to 200 units of electricity, but also to cover the gap between the lower costs of some companies and the higher costs of others. In a way, there is a discrimination against the companies that could keep their cost low, and also against consumers of such companies who have to pay for the companies who cannot keep their costs low.

The economic principle behind state subsidy is to keep prices low and to ensure equality of access. But that is not what happens in Pakistan’s power sector. Lifeline consumer should be given a subsidy, but since the subsidy continues with other consumers including those who can pay the full price, they get undue benefit. Such subsidy in fact puts pressure on the public exchequer, thus reducing the spending on social and development sectors. The government has to allocate more than Rs 200 billion to power subsidy.

[quote]In a way, there is a discrimination against companies that could keep their cost low[/quote]

There is a need to rethink the subsidy policy in Pakistan. Ideally, anything that helps people stay in business increases competition, and competition lowers consumer prices and reduces profits. But this principle does not work in the power sector of Pakistan. Instead, it has reduced competition, increased prices and profits, worsened an already mounting burden on the government, and hurt the performance of the power sector.

This method of subsidy could be changed, de-linking it with cost. That would mean the original cost of production and the pass through cost will lessen eventually, the government’s burden will decrease, and it will also be instrumental in energy conservation.

One of the mechanisms to give subsidy to lifeline consumers is to attach their subsidy amount to the social security system, such as the Benazir Income Support Program (BISP).

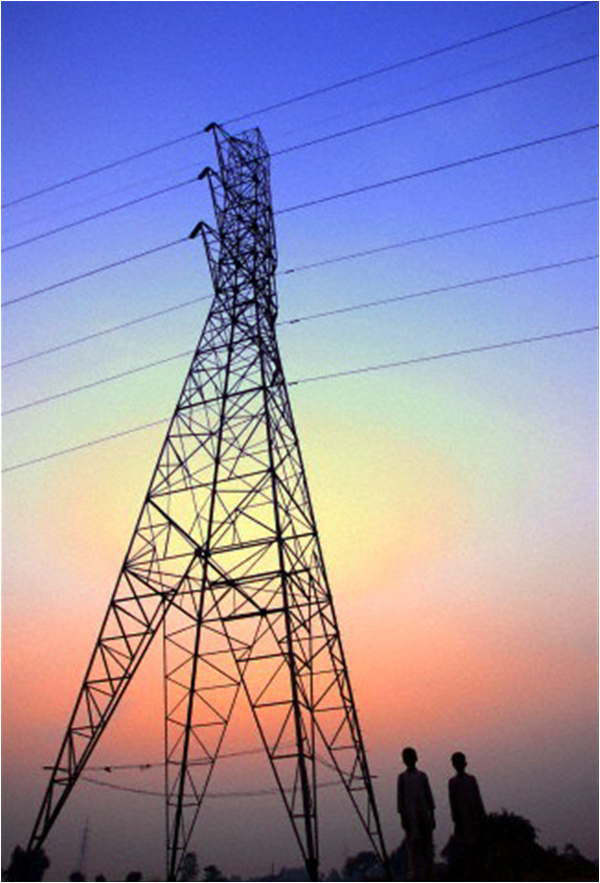

A second mechanism of channelling government subsidy in a productive manner would be to directly subsidize alternative energy. For instance, renewable energy needs subsidy to flourish and can pay off in the long run. Bangladesh was able to develop its solar energy sector by subsidizing the industry under a World Bank support program. They now have around 3.2 billion solar units and panels, and all high rise buildings are required to have solar panels in order to qualify for a power connection. Their roads, parks, and schools have already been solarized to a great extent.

[quote]Ideally, anything that helps people stay in business increases competition, and competition lowers consumer prices and reduces profits. But this principle does not work in the power sector of Pakistan[/quote]

The off-grid model of solar power can also be adopted. It will reduce the expenditure, and allow consumers to use it when it is needed, with the option to utilize the surplus power in the system. But it has a one time capital expenditure for which the government can collaborate with development agencies for the provision of solar units to consumers on subsidized rates. There is also a need to attract investors in the solar industry.

However, this assumes that the government will be fair in distributing these subsidies, making sure they are being utilized for the benefit of disadvantaged groups and not that of large businesses.

The author is a political economist and the chairperson of International Relations and Politics at the International Islamic University

Subsidy has become a political favour to both consumers and producers. We can’t even call it a market failure, because the power sector in Pakistan is not even a perfect market. A restructure plan developed in 1992 included three stages – decentralization, corporatization and privatization. Its been more than two decades since then, and we are still on the stage of corporatization.

Perhaps that is why the IMF has included the elimination of subsidies in its recent set of rather tough loan conditions. Recently, the head of the IMF mission in Pakistan stated that the government should only allow subsidy on power to consumers who use less than 50 units of electricity – which would include people who only run a fan and a light bulb. Consumers who use 50 units or less pay Rs 2 to Rs 4 per unit. Those who use less than 100 units pay Rs 4 to Rs 8, and the rates get progressively higher based on usage. The tariff for the producers is determined by the National Electric Power Regulatory Authority, and it is much higher than what the consumer is paying. On an average, the rates range between Rs 14 to Rs 18 per unit.

[quote]Subsidy has become a political favour to producers and consumers[/quote]

The purpose of the establishment of a regulator is to encourage private investors, and to give a differential tariff and not unified rates, because that amounts to killing the spirit of decentralization. The corporatization of the power sector was expected to ensure efficient production and lesser pilferages and line losses. But the fact that the power sector needs subsidies shows that the power production and distribution companies are inefficient entities.

[quote]There is a need to attract investors in the solar industry[/quote]

The issue becomes critical when we consider that it is a forced subsidy, and not a volunteer subsidy, which is mostly associated with lifeline consumers. Since the power sector in Pakistan is still transitioning from the public to the private sector, there persists a kind of confusion. The generation and distribution companies are supposed to apply to NEPRA for a tariff review, which then redetermines the rates based on a given mechanism. This rate is notified by the government, and is applicable to all the companies and not just the ones that asked for a higher tariff. The government therefore pays a cross subsidy, not just to people who use up to 200 units of electricity, but also to cover the gap between the lower costs of some companies and the higher costs of others. In a way, there is a discrimination against the companies that could keep their cost low, and also against consumers of such companies who have to pay for the companies who cannot keep their costs low.

The economic principle behind state subsidy is to keep prices low and to ensure equality of access. But that is not what happens in Pakistan’s power sector. Lifeline consumer should be given a subsidy, but since the subsidy continues with other consumers including those who can pay the full price, they get undue benefit. Such subsidy in fact puts pressure on the public exchequer, thus reducing the spending on social and development sectors. The government has to allocate more than Rs 200 billion to power subsidy.

[quote]In a way, there is a discrimination against companies that could keep their cost low[/quote]

There is a need to rethink the subsidy policy in Pakistan. Ideally, anything that helps people stay in business increases competition, and competition lowers consumer prices and reduces profits. But this principle does not work in the power sector of Pakistan. Instead, it has reduced competition, increased prices and profits, worsened an already mounting burden on the government, and hurt the performance of the power sector.

This method of subsidy could be changed, de-linking it with cost. That would mean the original cost of production and the pass through cost will lessen eventually, the government’s burden will decrease, and it will also be instrumental in energy conservation.

One of the mechanisms to give subsidy to lifeline consumers is to attach their subsidy amount to the social security system, such as the Benazir Income Support Program (BISP).

A second mechanism of channelling government subsidy in a productive manner would be to directly subsidize alternative energy. For instance, renewable energy needs subsidy to flourish and can pay off in the long run. Bangladesh was able to develop its solar energy sector by subsidizing the industry under a World Bank support program. They now have around 3.2 billion solar units and panels, and all high rise buildings are required to have solar panels in order to qualify for a power connection. Their roads, parks, and schools have already been solarized to a great extent.

[quote]Ideally, anything that helps people stay in business increases competition, and competition lowers consumer prices and reduces profits. But this principle does not work in the power sector of Pakistan[/quote]

The off-grid model of solar power can also be adopted. It will reduce the expenditure, and allow consumers to use it when it is needed, with the option to utilize the surplus power in the system. But it has a one time capital expenditure for which the government can collaborate with development agencies for the provision of solar units to consumers on subsidized rates. There is also a need to attract investors in the solar industry.

However, this assumes that the government will be fair in distributing these subsidies, making sure they are being utilized for the benefit of disadvantaged groups and not that of large businesses.

The author is a political economist and the chairperson of International Relations and Politics at the International Islamic University