Everyone knows that the most pertinent reason for failure of democracy in Pakistan is a series of coups carried out at regular interval by the Pakistani Army. Moving beyond this axiom, Aqil Shah, in his book The Army and Democracy: Military Politics in Pakistan has discussed why and how the political decisions taken by the civilian leadership aided in the evolution of Pakistan Army as the real centre of power.

In 1947, after partition of India, Pakistan was formed with anti-India/Hindu cries and amidst fear-psychosis of being gobbled up by India. Acting as an institution, the Pakistan Army exploited these fears to establish itself as an omnipotent institution. With a strong army ready to interfere, the process of democratization suffered. This problem started in early years of Pakistan when the process to build a strong military force was started. Mainly due to political naivety, Pakistan’s political leaders failed to foresee or politically analyze the repercussions of endorsement of Major Akbar Khan’s plan of intrusion in Kashmir valley which led to first India-Pakistan war in 1948. To describe the situation Aqil Shah has cited General Frank Messervy (1947-48), who presciently lamented the early erosion of the military’s apolitical tradition: “I am fed up with what is going on in Kashmir… all behind my back… Politicians using soldiers and soldiers allowing themselves to be used, without the proper approval of their superiors are setting a bad example for the future” (42).

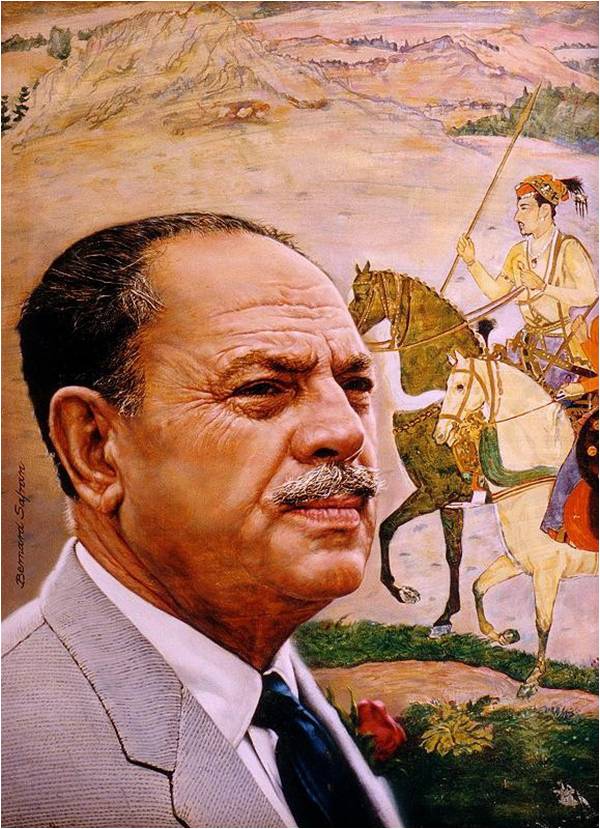

Perhaps to placate or adjust the demands of the Army after Rawalpindi conspiracy in 1951, the process of militarization of civilian rule was started. General Ayub Khan became a part of decision making process by the council of ministers. Citing one of Ayub Khan’s biographers, Atiq Shah writes the commander in chief became the sole source for “giving direct advice to the government instead of receiving it through a Minister.” His counsel was obtained before any big or vital decision was taken by the government, “whether it is concerned with commerce or education, foreign affairs or the interior, industrial development or social welfare” (62). This prepared background for the coup in 1958. Instead of being opposed, General Ayub Khan was institutionally assisted and supported by the bureaucracy, judiciary, and religious groups. During his eleven-year tenure, Ayub Khan started the practice of civilianization of the military rule and getting elected through popular vote. The former helped in co-option of civilian power elite while the later legitimize the coup. Both practices had been adopted by the later military head of states.

[quote]Ayub Khan started the practice of civilianization of military rule[/quote]

After dismemberment of East Pakistan in 1971, Army’s image had been sullied while ZA Bhutto became a hero. He became the Prime Minister. Under him, forgetting its structural strength, the civilian government tried to impose its authority over the Army. Undermining Army’s power Bhutto created a Federal Security Force (FSF) - a paramilitary force. Bhutto’s policies and electoral malpractices in 1977 created a policy paralysis in Pakistan. The opposition leaders and Islamic groups were on the streets. Instead of fighting politically they requested Army to remove the government and take over. As a result, on 5 July 1977, Bhutto’s handpicked General Ziaul Haq overthrew the civilian government and imposed martial law in Pakistan (136). During General Zia’s period, Army was Islamized and the process of sunnification of society was encouraged. He is solely responsible for Pakistan teetering on the edge of the abyss. He ruled over the country till he died in a plane crash in 1988 (137).

As a pivot, the Army regulates the democratic regime to satisfy its institutional interests. After domestic protests under the banner of Movement for Restoration of Democracy (MRD) and by external powers, democracy was restored in Pakistan in 1990. In ensuing elections the Inter Service Intelligence (ISI), known for its institutional notoriety, funneled money from a special fund financed by the private Mehran Bank (headed by Younis Habib banker) to IJI politicians to boost their electoral campaign (171). Unfortunately, it did not win and Benazir Bhutto’s PPP with its coalition partners formed the government. That government was soon replaced by another one under the leadership of Nawaz Sharif. Both were repeatedly ousted from power because they tried to tame the Army, which backfired.

The third coup was carried out by General Pervez Musharraf, who ousted Nawaz Sharif in 1999. Nawaz Sharif, himself a political product of the Army, failed to learn a lesson that it acts as an institution and not goaded by an individual. He paid the price. Though considered a ‘liberal General’, Musharraf too ruled like his military predecessors. After he was ousted from power through mass protests, democracy returned to Pakistan in 2008. After a violent election, leading to assassination of PPP chairwoman Benazir Bhutto, the civilian government under Asif Ali Zardari came into power. In 2013, the PPP government completed its tenure and, the first time in the history of Pakistan, there was a democratic transfer of power. From 2008 to date, there have been incidents, which Aqil Shah has chronologically explained, when tensions between the government and army brewed, but they had been craftily managed.

Only through democracy can Pakistan fight against its predators. The current civilian government must prepare a base on which democracy can flourish. This has to be done not by fighting against the Army, which may backfire, but by gradually dislocating and replacing its deep rooted institutional presence.

This book is an erudite work to understand the relationship between democracy and Army in Pakistan.

In 1947, after partition of India, Pakistan was formed with anti-India/Hindu cries and amidst fear-psychosis of being gobbled up by India. Acting as an institution, the Pakistan Army exploited these fears to establish itself as an omnipotent institution. With a strong army ready to interfere, the process of democratization suffered. This problem started in early years of Pakistan when the process to build a strong military force was started. Mainly due to political naivety, Pakistan’s political leaders failed to foresee or politically analyze the repercussions of endorsement of Major Akbar Khan’s plan of intrusion in Kashmir valley which led to first India-Pakistan war in 1948. To describe the situation Aqil Shah has cited General Frank Messervy (1947-48), who presciently lamented the early erosion of the military’s apolitical tradition: “I am fed up with what is going on in Kashmir… all behind my back… Politicians using soldiers and soldiers allowing themselves to be used, without the proper approval of their superiors are setting a bad example for the future” (42).

Perhaps to placate or adjust the demands of the Army after Rawalpindi conspiracy in 1951, the process of militarization of civilian rule was started. General Ayub Khan became a part of decision making process by the council of ministers. Citing one of Ayub Khan’s biographers, Atiq Shah writes the commander in chief became the sole source for “giving direct advice to the government instead of receiving it through a Minister.” His counsel was obtained before any big or vital decision was taken by the government, “whether it is concerned with commerce or education, foreign affairs or the interior, industrial development or social welfare” (62). This prepared background for the coup in 1958. Instead of being opposed, General Ayub Khan was institutionally assisted and supported by the bureaucracy, judiciary, and religious groups. During his eleven-year tenure, Ayub Khan started the practice of civilianization of the military rule and getting elected through popular vote. The former helped in co-option of civilian power elite while the later legitimize the coup. Both practices had been adopted by the later military head of states.

[quote]Ayub Khan started the practice of civilianization of military rule[/quote]

After dismemberment of East Pakistan in 1971, Army’s image had been sullied while ZA Bhutto became a hero. He became the Prime Minister. Under him, forgetting its structural strength, the civilian government tried to impose its authority over the Army. Undermining Army’s power Bhutto created a Federal Security Force (FSF) - a paramilitary force. Bhutto’s policies and electoral malpractices in 1977 created a policy paralysis in Pakistan. The opposition leaders and Islamic groups were on the streets. Instead of fighting politically they requested Army to remove the government and take over. As a result, on 5 July 1977, Bhutto’s handpicked General Ziaul Haq overthrew the civilian government and imposed martial law in Pakistan (136). During General Zia’s period, Army was Islamized and the process of sunnification of society was encouraged. He is solely responsible for Pakistan teetering on the edge of the abyss. He ruled over the country till he died in a plane crash in 1988 (137).

As a pivot, the Army regulates the democratic regime to satisfy its institutional interests. After domestic protests under the banner of Movement for Restoration of Democracy (MRD) and by external powers, democracy was restored in Pakistan in 1990. In ensuing elections the Inter Service Intelligence (ISI), known for its institutional notoriety, funneled money from a special fund financed by the private Mehran Bank (headed by Younis Habib banker) to IJI politicians to boost their electoral campaign (171). Unfortunately, it did not win and Benazir Bhutto’s PPP with its coalition partners formed the government. That government was soon replaced by another one under the leadership of Nawaz Sharif. Both were repeatedly ousted from power because they tried to tame the Army, which backfired.

The third coup was carried out by General Pervez Musharraf, who ousted Nawaz Sharif in 1999. Nawaz Sharif, himself a political product of the Army, failed to learn a lesson that it acts as an institution and not goaded by an individual. He paid the price. Though considered a ‘liberal General’, Musharraf too ruled like his military predecessors. After he was ousted from power through mass protests, democracy returned to Pakistan in 2008. After a violent election, leading to assassination of PPP chairwoman Benazir Bhutto, the civilian government under Asif Ali Zardari came into power. In 2013, the PPP government completed its tenure and, the first time in the history of Pakistan, there was a democratic transfer of power. From 2008 to date, there have been incidents, which Aqil Shah has chronologically explained, when tensions between the government and army brewed, but they had been craftily managed.

Only through democracy can Pakistan fight against its predators. The current civilian government must prepare a base on which democracy can flourish. This has to be done not by fighting against the Army, which may backfire, but by gradually dislocating and replacing its deep rooted institutional presence.

This book is an erudite work to understand the relationship between democracy and Army in Pakistan.