Pakistan has always been a dangerous place for journalists, but threats to their safety have never been as multifaceted as they are today. Some of these threats arise from the state itself, or its institutions, which try to monopolize the rhetoric and narrative on certain “sensitive issues.” But the most dangerous of them come from extremist groups. These groups have the same interest as the military in controlling the national narrative on certain issues. Unlike the military, these groups have a far more expansive list of journalist no-no’s, which, if breached, warrant an immediate green-light for murder.

The Pakistani government responded to the attack on Hamid Mir by setting up a judicial probe commission. Often, these commissions can keep their findings confidential and inaccessible to the public at large. Other times, if a victim survives an attempt on their life, they can be provided ad hoc and provisional police protection at the discretion of the provincial police service. However, there are no institutionalized mechanisms journalists rely upon to guarantee their long-term safety.

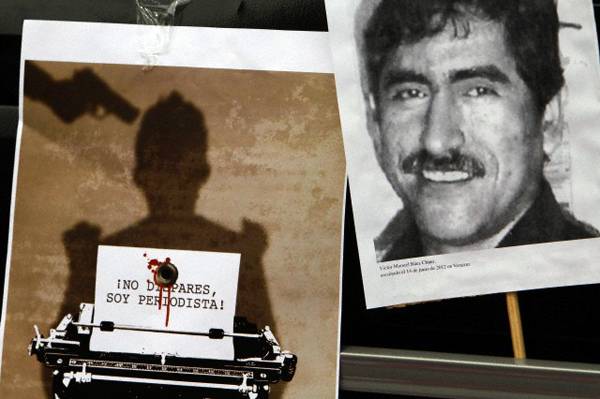

The situation was perhaps even worse in Colombia, where journalists were regularly killed by both the military and the narco-terrorists for reporting on the brutal fighting between the two forces and political corruption. The situation has calmed down considerably in the recent times, but Mexico has concurrently faced an uptick of violence against journalists by drug cartels. These cartels have been waging a war among themselves and against Mexican anti-drug authorities, and target journalists who are dedicated to covering all aspects of the drug war.

Both countries have created a two-part regime in order to deal with violence against journalists. First, they created a specialized agency in their ministries of interior to provide police protection to journalists who have faced threats. Mexico created the “Protection Mechanism for Human Rights Defenders and Journalists” for its interior ministry to handle requests for police protection from journalists. Colombia has similarly tasked its National Protection Agency with providing security to journalists. Colombia has also put in place a procedure to evaluate threats to journalists through its Risk Evaluation Committee, which can offer “relocation assistance, bulletproof vests, armed escorts, and armored cars”.

[quote]Mexico and Colombia plan to make violence against journalists a special crime[/quote]

The administration of this protection service can range from a purely federal force of officers tasked with protecting journalists and collecting intelligence about their threats, or special wings in the provincial police created to carry out the same task.

Second, both countries are working on amending their penal codes to make violence or murder against a journalist a special crime, allowing the Attorney Generals to pursue those as specialized cases. As such, Mexico created “the Special Prosecutor’s Office for Crimes against Journalist,” which exclusively investigates and prosecutes crimes against journalists. Though the special prosecutor has been criticized for failing to prosecute cases effectively, the office has the potential of satisfying the need for a judicial institution that can provide security and support for the valuable work journalists perform.

It is the nature of the work that journalists perform which inspired the United Nations to create a Plan of Action on the Safety of Journalists and the Issue of Impunity. This document begins with a powerful quote from Barry James, a French reporter and editor, who said: “Every journalist killed or neutralized by terror is an observer less of the human condition. Every attack distorts reality by creating a climate of fear and self-censorship.”

Journalists provide a special public service with their work by informing the public of wrongdoings, whether by cops or by robbers. This leaves them open to attacks from both sides, the criminal underworld and the state agencies tasked with battling them. Further, due to the public nature of their work, journalists can be easily identified and targeted, unlike common citizens. These are some of the reasons the United Nations has moved to recognize the international problem of violence against journalists.

The report goes onto state that “the threat [to journalists] posed by non-state actors such as terrorist organizations and criminal enterprises is growing.” The UN Plan has been to “strengthen legal frameworks and enforcement mechanisms designed to ensure the safety of journalists.” This includes providing advice and resources to countries attempting to protect journalists, while also encouraging various UN agents and groups to report threats to journalists among the international community. Various UN organizations study threats to journalists, such as the Special Rapporteur on the Promotion and Protection of the Right to Freedom of Opinion and Expression, and UNESCO, which publishes biennial reports on journalist safety around the globe.

None of these are overnight solutions to the threats faced by Pakistani journalists. Despite changing their penal codes and creating agencies to protect journalists, there is criticism that the Colombian and Mexican authorities are not doing enough. However, unless Pakistan’s government begins the long process of addressing the multifaceted threats to reporters with institutionalized protection mechanisms in the form of new laws and agencies, the future of Pakistani journalism is grim.

The Pakistani government responded to the attack on Hamid Mir by setting up a judicial probe commission. Often, these commissions can keep their findings confidential and inaccessible to the public at large. Other times, if a victim survives an attempt on their life, they can be provided ad hoc and provisional police protection at the discretion of the provincial police service. However, there are no institutionalized mechanisms journalists rely upon to guarantee their long-term safety.

The situation was perhaps even worse in Colombia, where journalists were regularly killed by both the military and the narco-terrorists for reporting on the brutal fighting between the two forces and political corruption. The situation has calmed down considerably in the recent times, but Mexico has concurrently faced an uptick of violence against journalists by drug cartels. These cartels have been waging a war among themselves and against Mexican anti-drug authorities, and target journalists who are dedicated to covering all aspects of the drug war.

Both countries have created a two-part regime in order to deal with violence against journalists. First, they created a specialized agency in their ministries of interior to provide police protection to journalists who have faced threats. Mexico created the “Protection Mechanism for Human Rights Defenders and Journalists” for its interior ministry to handle requests for police protection from journalists. Colombia has similarly tasked its National Protection Agency with providing security to journalists. Colombia has also put in place a procedure to evaluate threats to journalists through its Risk Evaluation Committee, which can offer “relocation assistance, bulletproof vests, armed escorts, and armored cars”.

[quote]Mexico and Colombia plan to make violence against journalists a special crime[/quote]

The administration of this protection service can range from a purely federal force of officers tasked with protecting journalists and collecting intelligence about their threats, or special wings in the provincial police created to carry out the same task.

Second, both countries are working on amending their penal codes to make violence or murder against a journalist a special crime, allowing the Attorney Generals to pursue those as specialized cases. As such, Mexico created “the Special Prosecutor’s Office for Crimes against Journalist,” which exclusively investigates and prosecutes crimes against journalists. Though the special prosecutor has been criticized for failing to prosecute cases effectively, the office has the potential of satisfying the need for a judicial institution that can provide security and support for the valuable work journalists perform.

It is the nature of the work that journalists perform which inspired the United Nations to create a Plan of Action on the Safety of Journalists and the Issue of Impunity. This document begins with a powerful quote from Barry James, a French reporter and editor, who said: “Every journalist killed or neutralized by terror is an observer less of the human condition. Every attack distorts reality by creating a climate of fear and self-censorship.”

Journalists provide a special public service with their work by informing the public of wrongdoings, whether by cops or by robbers. This leaves them open to attacks from both sides, the criminal underworld and the state agencies tasked with battling them. Further, due to the public nature of their work, journalists can be easily identified and targeted, unlike common citizens. These are some of the reasons the United Nations has moved to recognize the international problem of violence against journalists.

The report goes onto state that “the threat [to journalists] posed by non-state actors such as terrorist organizations and criminal enterprises is growing.” The UN Plan has been to “strengthen legal frameworks and enforcement mechanisms designed to ensure the safety of journalists.” This includes providing advice and resources to countries attempting to protect journalists, while also encouraging various UN agents and groups to report threats to journalists among the international community. Various UN organizations study threats to journalists, such as the Special Rapporteur on the Promotion and Protection of the Right to Freedom of Opinion and Expression, and UNESCO, which publishes biennial reports on journalist safety around the globe.

None of these are overnight solutions to the threats faced by Pakistani journalists. Despite changing their penal codes and creating agencies to protect journalists, there is criticism that the Colombian and Mexican authorities are not doing enough. However, unless Pakistan’s government begins the long process of addressing the multifaceted threats to reporters with institutionalized protection mechanisms in the form of new laws and agencies, the future of Pakistani journalism is grim.