Tehran ho gar aalam-e-mashreq ka Geneva

Shaayad kura-e-arz kee tadqeer badal jaae

If Tehran could become the Geneva of the Orient

The fortunes of this hemisphere might turn

(Iqbal in his poem Jamiyat-e-Aqwam or League of Nations)

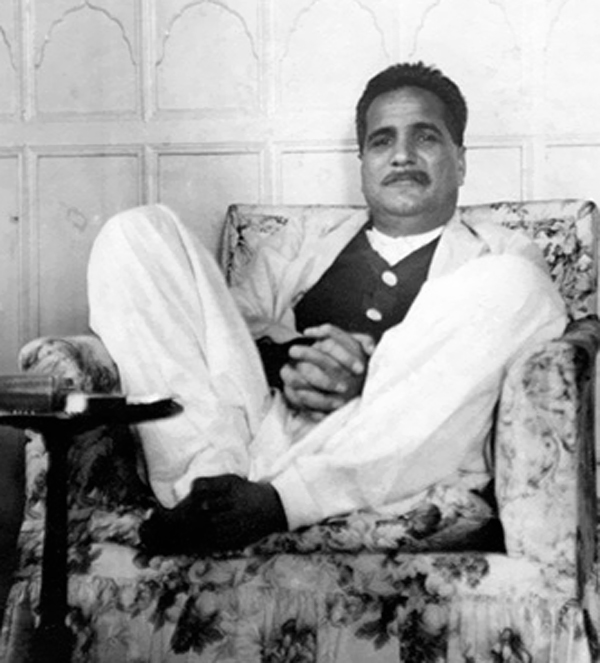

Iran fascinated Iqbal. His doctoral thesis titled The Development of Metaphysics in Persia, submitted in 1908, at the University of Munich in Germany, is a comprehensive survey of Persian philosophical thought over the centuries – from Zoroastrian times to the Islamic period up to the end of the 19th century. Iqbal admired Iranians for their refinement of manners, philosophical mind, ancient civilization and high culture. In his collection of essays and articles, published as Maqaalaat-e-Iqbal in 1963, Iqbal observed that the most important event in the history of Islam was the conquest of Persia as it played a major role in the subsequent intellectual and cultural development of the religion.

Delivering a lecture at Aligarh in March 1910 on the topic of The Muslim Community - A Sociological Survey, Iqbal averred: “Our Muslim civilization is a product of the cross-fertilization of the Semitic and the Aryan ideas. It inherits the softness and refinement of an Aryan mother and the sterling character of a Semitic father. The conquest of Persia gave the Muslims what the conquest of Greece gave to the Romans; but for Persia our culture would have been absolutely one-sided.”

[quote]"Muslims have inherited the softness and refinement of an Aryan mother and the sterling character of a Semitic father"[/quote]

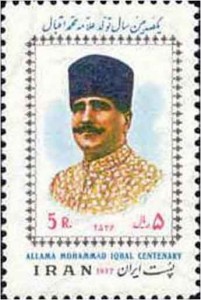

on Iqbal's centenary

Iqbal’s research for his doctoral thesis on Persian philosophy had a major impact on his thinking; although he had started writing verses in Urdu as a student in the 1890s, he decided to compose poetry in Persian during his stay in Europe for his Ph.D. He explains in Asraar-e-Khudi (The Secrets of the Self) his decision to switch to Persian from Urdu:

Although the language of Hind is sweet as sugar

Yet sweeter is the fashion of Persian speech

My mind was enchanted by its loveliness

My pen became a twig of the Burning Bush

Because of the loftiness of my thoughts

Persian alone is suitable to them (Translation by R.A Nicholson)

Although Urdu poetry draws heavily on Persian idiom and imagery, Iqbal found Persian more suited to this thought and temperament and a better means of communication to a wider audience in the Indian sub-continent as well as other countries of the Muslim world. At the end, more than half and nearly two-thirds of Iqbal’s poetry was in Persian and only above one-third was in Urdu; Out of over 12,000 verses, around 7000 verses are in Persian and nearly 5000 verses are in Urdu; Out of his ten collections of poetry, six are in Persian, only three in Urdu and his last collection Arghaman-e-Hejaz (The Gift of Hejaz), published posthumously, is partly in Persian and partly in Urdu.

His first collection of poetry Asrar-e-Khudi, all in Persian, was published in 1915 while his first Urdu collection Bang-e-Dara was published in 1924. When repeatedly asked about his preference for Persian, Iqbal is said to have remarked that he feels helpless as most ideas come to his mind in Persian.

[quote]In turn, Iran has also been fascinated by Iqbal Lahori[/quote]

Iqbal embraced famous Persian poet Rumi as his spiritual guide and modelled his style of poetry on that of his spiritual mentor’s masterpiece – Mathnawi-e-Rumi. He had deeply studied other greats of Persian poetry at home (as at college he formally studied Arabic, Philosophy, English Literature and Economics) and proudly declared in Zabur-e-Ajam (Persian Psalms)

Mara binger key der Hindustan deegar namee beenee

Brahmin zadai ramz ashnae Room-o-Tabriz ast

Look at me, you will never find another in India

Who like me, a Brahmin’s scion, understands the secrets of Rum and Tabriz

In a verse in Payaam-e-Mashreq (Message from the East), Iqbal established his link with Shiraz – the cradle of art and culture in Iran – in the following way

Tanam gulee ze khayaban jannat-e-Kashmir

Dil az hareem-e-Hejaz va nawa ze Shiraz ast

Physically I am a flower from the garden of Kashmir

My heart is from the sanctuary of Hejaz and my melody is from Shiraz

Two of Iqbal’s greatest desires remained unfulfilled: a pilgrimage to Hejaz and a visit to Iran. In 1933, Iqbal went to Afghanistan (he was invited by the King) and longed to visit Iran via Herat but could not go beyond Kandahar during this journey.

In turn, Iran has also been fascinated by Iqbal Lahori – someone who never visited Iran, did not study Persian formally or firsthand observe their way of life yet produced such gems in his Persian poetry. However, it should be noted that Iqbal was hardly known or appreciated in Iran during his lifetime. In 1932, when Iranian monarch Reza Shah Pahalvi invited Bengali poet and first Indian Nobel Laureate Rabindranath Tagore to visit Iran, Iqbal felt snubbed and slighted. Although Iqbal sent his Persian poetry books to academics in Iran, he was not well known beyond the academic circles in Iran during his lifetime.

After Iqbal’s death in 1938, Iran’s poet laureate (known as Malak-o-Shaura in Iran) Mohammed Taqi Bahar popularized Iqbal in Iran. He paid rich tributes to Iqbal in his verses and termed the “present age as the special period of Iqbal who is heir to thousand years of Islamic cultural heritage”. By early 1950s Iqbal was well known among Iran’s intelligentsia in addition to its academic circles.

[quote]Iqbal felt snubbed and slighted[/quote]

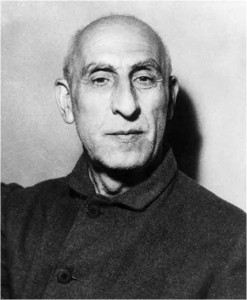

In 1952, Iranian Prime Minister Mohammed Mossadeq, who was a national hero due to his oil nationalization policy, broadcast a special radio message on Iqbal Day and eulogized his role in Indian Muslims’ struggle against British imperialism (Mossadeq was himself embroiled in confrontation with the Britain over the oil-nationalization issue). After Mossadeq’s message was broadcast, Iqbal’s reputation and popularity went up in leaps and bounds. By the end of the 1950s, the complete Persian works of Iqbal were published in Iran in addition to translations of his Urdu poetry and his famous lectures on the reconstruction of religious thought in Islam. In the 1960s, his doctoral thesis on Persian philosophy was translated from English to Persian and soon established itself as the standard work on Persian philosophy among Iranians.

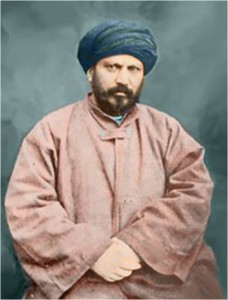

Iran, although not formally colonized like India, had a long history of struggle against Western imperialism and foreign interference in its internal affairs during the twentieth century – British and Russian between 1893 and 1953 and American from 1953-1979. Iran also had a tradition of religious modernism in which figure such as Jamaluddin Afghani, born and educated in Iran, played a key role. By 1970, Iranian intellectuals found themselves dealing with two main questions: Western imperialism or physical and intellectual domination of the West and the role of Islam in the state. It is in this context that Iqbal’s message of Islamic revival or reconstruction of religious thought in Islam and his poetry of self-awareness of and freedom from colonialism struck a resonant and responsive chord among Iranian intellectuals. It needs to be mentioned that Iqbal was not against the West per se (as he has praised the West for its knowledge, learning and technology) but criticised it for its materialism, colonialism and imperialism.

By 1970, Iran had “discovered” Iqbal. His verses appeared on banners and his poetry was recited in meetings of the intellectuals who became the leading lights of the 1979 revolution. Although Iqbal inspired many intellectuals, four names deserve special mention – Ali Shariati, Mehdi Bazargan, Sayyed Ali Khamenei and Dr Abdulkarim Soroush. Ali Shariati, considered to be the ideologue of the Iranian revolution, and Ali Khamenei, currently the Supreme Leader, have written scholarly books on Iqbal; Bazargan, Iran’s first Prime Minister after the 1979 revolution, and Dr Soroush, a former revolutionary turned chief critic of the current religious government who lives in exile and has been hailed as the Martin Luther of Islam in the West, have acknowledged their intellectual debt to Iqbal in their writings.

In 1986, President Khamenei, currently the Supreme Leader, toured Pakistan and quoted the following shayr from Iqbal:

Khawaja az khoon-e-reg-e-mazdoor saazad laal nab

Kishte dehkaan az jafaye deh khudayian shood kharab

Inqbalab ay Inqalab ay Inqalab

The capitalist extracts red wine from the worker’s blood

The peasant’s crop is spoiled by the oppression of the landlords

Revolution, Oh Revolution, Oh Revolution

Ali Shariati, a Sorbonne educated sociologist, embraced Iqbal as his role model just as Iqbal had adopted Rumi as his mentor; Shariati perhaps popularized Iqbal the most in Iran through his lectures at Hosseniyeh-e-Ershad, a religious center with a modern lecture hall which became the epicenter of revolutionary activity during the 1970s and was also briefly closed down by the Shah’s regime. Iqbal’s evocative and moving Persian elegy for Imam Hussein (AS) adorned the walls and pillars of Hosseniyeh-e-Ershad’s stage. No better example of Iran’s admiration and appreciation for Iqbal can be given than this: In a country which is overwhelmingly Shia and has produced thousands of poets who have composed Persian elegies for Imam Hussain, Iqbal is accorded the pride of place in the pantheon of Persian elegy writers.

After 1947, the readership of Persian in India and Pakistan has declined to lamentably low levels; both Pakistanis and Indians have given up reading Persian. With a steep decline in Urdu readership in India after partition, Indians, for whom Iqbal wrote Tirana-e-Hindi, are twice detached from Iqbal. With nearly two- thirds (about 60%) of his poetry in Persian it is now left to Iranians to enjoy and appreciate Iqbal’s verses.

[quote]Two of Iqbal's greatest desires remained unfulfilled[/quote]

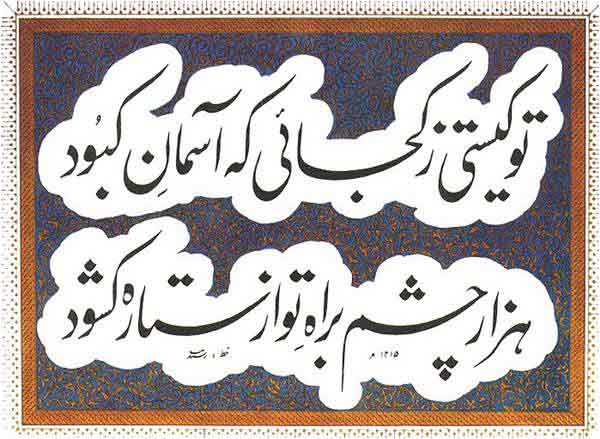

No wonder, Iqbal composed a special poem for Iranians in Persian – whose oft-quoted verses are full of fire and feeling. In this powerful and passionate poem in Zabur-e-Ajam (Persian Psalms), Iqbal poured out his love and affection for the Iranians, gave them glad tidings for their future and foresaw a savior who would deliver them salvation from slavery and misery.

Like a tulip’s flame I burn

In your presence as I turn;

By my life, and yours, I swear

Youth of Persia ever fair!

I have dived, and dived again

With my thoughts into life’s brain

Until I prevailed to find

Every secret of your mind.

Sun and moon—I gazed on these

Far beyond the Pleiades,

And rebuilt a sanctuary

In your infidelity.

I have twisted well the blade

Till its edge was sharper made;

Pale the gleam and lustreless

Wasted in your wilderness.

My thought’s images dispense

To the Orient’s indigence

The bright ruby that I gain

From your mines of Badakhshan.

Comes the man, to free at last

Slaves confined in fetters fast;

Through the windows in the wall

Of your prison I see all.

Make a ring about me now;

In my breast a fire’s aglow

That your forebears lit one day,

Things of water and of clay.

(Translation by A.J.Arberry)

The author lived in Iran during the revolution and tweets at @AmmarAliQureshi.