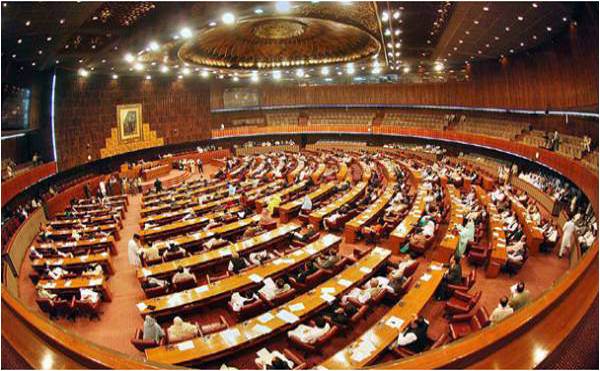

The Pakistan Protection Ordinance (PPO) is the newest attempt by the Sharif administration to create laws that takes a “hard stance” against terrorism, with specific attention to “foreign enemy combatants.” The Ordinance has been approved by the president as well as the National Assembly, but is facing opposition at the Senate, with some politicians seeking the Supreme Court to overturn the Ordinance as violative of the Constitution. By examining the international precedent for the PPO and the way in which it could be used to attack fundamental rights, one can see there is an imbalance between national securities and freedoms.

International Precedent: Patriot Act

In the aftermath of the 9/11 terrorist attacks, the U.S. government (led by the Bush Administration) passed the PATRIOT Act, which greatly expanded the powers of the president and limited certain rights for citizens suspected of terrorist activity. Asad Rahim Khan, a columnist and attorney in Lahore, explains that it was the PATRIOT Act that allowed the US government to devolve and attack constitutional rights in the name of “fighting terrorism.” He states: “If anything has poisoned the image of the United States abroad, it’s been the spectre of ‘enhanced interrogations’, ‘extraordinary renditions’, ‘black spots’, Guantanamo Bay, and a sting of other vehicles designed to deprive a person of their rights.”

All of these practices can be traced at least partially to the PATRIOT Act, which has not stopped developing countries from adopting similar laws to battle their own domestic terrorists. Nighat Dad, lawyer and executive director for Digital Rights Foundation, explains that the “US PATRIOT Act itself set the worst precedent for developing countries and that’s what we are witnessing in Pakistan in the form of Fair Trial Bill and PPO.”

Relevant Provisions

The final draft of the PPO has not been agreed on, as the People’s Party has asked for several amendments to be made to the bill before they can approve of the law. However, some of the provisions that have been attacked by critics include:

a. A suspected terror may be “preventively detained” for a period of up to 90 days based on the security agencies’ “reasonable belief” that they are or could be engaged in terrorist acts.

b. Suspects who are deemed to be enemy combatants or enemy aliens can be indefinitely detained without a trial and held in military facilities or internment camps.

c. Security forces are given the right to shoot suspects on sight or detain them in secret locations without providing access to civilian courts

d. Security forces can engage in arrest, searches and seizures without a court warrant.

e. Allows the court to strip persons of their citizens.

[quote]"How can the state absolve itself of the crime of enforcing disappearances?"[/quote]

Legalizing Disappearances

The issue of enforced disappearances carried out by security agencies has plagued Pakistan for several years, especially in Balochistan. Rather than attempt to prohibit the illicit and unconstitutional kidnapping of citizens by security agencies, critics like Advocate Athar Minallah argue that the PPO is “meant to regularize enforced disappearances.” Asad Jamal, attorney and columnist, asks: “How can the state absolve itself of the crime of enforcing disappearances against thousands of its own citizens…Has any country [other than Pakistan] declared enforced disappearances legal?”

Politicized Use of Detention

Not only does the PPO legalize enforced disappearances, its broad and vague wording could be used to stifle and silence political dissent. The Secretary General of the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan stated that the law could be used to suppress human rights activists around the country. Nighat Dad explains that the opaque nature of the words used in the PPO “can be utilized against journalists, politicians, minorities, students, activists and groups who are… criticizing government’s policies.” Asad Jamal explained that the PPO could “be used to nab all kinds of threats including non-armed political ones too.”

Assumption of Guilt

The next issue that has been raised by attorneys reviewing the PPO is the presumptions of guilt that the PPO encourages. Generally, everyone is innocent of crimes until they are proven guilty, but when it comes to suspected enemy combatants in Pakistan, the opposite is now true. Lawyer and columnist, Yasir Latif Hamdani, says laws like the PPO “shifts the burden of proof on the arrested person, not only of his innocence but of his citizenship. The assumption would be that a person is an enemy alien waging war against Pakistan unless he can prove otherwise. Allowing such a presumption seems counterintuitive to the model of justice in Pakistan, and most of the world, that all individuals are innocent until proven guilty.

Reinventing the Wheel

The question asked by many critics of the PPO is why the law was needed in the first place when there are already a slew of anti-terror laws on the books in Pakistan? Asad Jamal argued that “the preamble to PPO is meant to provide for waging of war against Pakistan, an offence [which is] already provided for in the Pakistan Penal Code.” He goes on to question, “Why do we need a new law in the form of PPO?” Asad Rahim Khan agreed, arguing that it is “better to actually enforce the old laws than invent new ones we won’t enforce either.”

Potential Advantages of PPO

Barrister Amjad Malik, chair of Pakistani Lawyers in the UK, disagrees with the critics, arguing that the PPO was necessary in the absence of specific laws to deal with enemy combatants and terrorists in Pakistan. He explained that some of the PPO provisions deemed draconian by critics exist in current law; for example, security agencies have possessed the right to preventatively detain suspects before the PPO.

Even critics like Asad Rahim Khan have written that the saving grace of the PPO is its mention of creating special jails for suspects and safe-houses to provide greater security for witnesses, judges, lawyers, and court employees. If these aspirations come to life, they could ameliorate the abysmal conviction rates in terrorism cases and allow for the courts to effectively perform their functions without fearing violent retribution by terrorists.

The Role of the Court

In the process of the Senate confirmation, an opposition-led group including PTI has filed for a review of the PPO. However, some in the People’s Party have objected to this, with Senator Farhatullah Babar saying that “it is unwise to take a parliamentary battle to other forums and invite their interference in matters that fall within the domain of parliament alone.”

However, legal experts interviewed generally agreed that the Pakistani judiciary could legitimately get involved in assessing the constitutionality of the PPO. According to Yasir Latif Hamdani, “The courts should get involved…[they] have a duty to test every law on the touchstone of fundamental rights.” If the Pakistani judiciary were to take such a case, Sindhyar Talpur, managing editor of South Asia Jurist, says they could look to the UK Supreme Court for an example. In A and Others v Secretary of State, Talpur says, the House of Lords rejected a law passed by the government to allow indefinite detention of terrorists because it violated the fundamental rights of British citizens.

Balancing Security and Freedoms

The creation of anti-terror legislation like the PPO or Fair Trial Act effect Pakistan’s balance of security and freedom in the age of terrorism. Chief Justice Jillani recently delivered a speech where he stated that all government actors were duty-bound to abide by the rule of law and ensure human dignity, even in the face of terrorism. He explained that the “rule of law was an unending quest.” As such, it is the duty of the ruling administration to “Protect Pakistan” not only from terrorists, but from illegal actions by the state itself, like disappearances, torture or extrajudicial killing.

International Precedent: Patriot Act

In the aftermath of the 9/11 terrorist attacks, the U.S. government (led by the Bush Administration) passed the PATRIOT Act, which greatly expanded the powers of the president and limited certain rights for citizens suspected of terrorist activity. Asad Rahim Khan, a columnist and attorney in Lahore, explains that it was the PATRIOT Act that allowed the US government to devolve and attack constitutional rights in the name of “fighting terrorism.” He states: “If anything has poisoned the image of the United States abroad, it’s been the spectre of ‘enhanced interrogations’, ‘extraordinary renditions’, ‘black spots’, Guantanamo Bay, and a sting of other vehicles designed to deprive a person of their rights.”

All of these practices can be traced at least partially to the PATRIOT Act, which has not stopped developing countries from adopting similar laws to battle their own domestic terrorists. Nighat Dad, lawyer and executive director for Digital Rights Foundation, explains that the “US PATRIOT Act itself set the worst precedent for developing countries and that’s what we are witnessing in Pakistan in the form of Fair Trial Bill and PPO.”

Relevant Provisions

The final draft of the PPO has not been agreed on, as the People’s Party has asked for several amendments to be made to the bill before they can approve of the law. However, some of the provisions that have been attacked by critics include:

a. A suspected terror may be “preventively detained” for a period of up to 90 days based on the security agencies’ “reasonable belief” that they are or could be engaged in terrorist acts.

b. Suspects who are deemed to be enemy combatants or enemy aliens can be indefinitely detained without a trial and held in military facilities or internment camps.

c. Security forces are given the right to shoot suspects on sight or detain them in secret locations without providing access to civilian courts

d. Security forces can engage in arrest, searches and seizures without a court warrant.

e. Allows the court to strip persons of their citizens.

[quote]"How can the state absolve itself of the crime of enforcing disappearances?"[/quote]

Legalizing Disappearances

The issue of enforced disappearances carried out by security agencies has plagued Pakistan for several years, especially in Balochistan. Rather than attempt to prohibit the illicit and unconstitutional kidnapping of citizens by security agencies, critics like Advocate Athar Minallah argue that the PPO is “meant to regularize enforced disappearances.” Asad Jamal, attorney and columnist, asks: “How can the state absolve itself of the crime of enforcing disappearances against thousands of its own citizens…Has any country [other than Pakistan] declared enforced disappearances legal?”

Politicized Use of Detention

Not only does the PPO legalize enforced disappearances, its broad and vague wording could be used to stifle and silence political dissent. The Secretary General of the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan stated that the law could be used to suppress human rights activists around the country. Nighat Dad explains that the opaque nature of the words used in the PPO “can be utilized against journalists, politicians, minorities, students, activists and groups who are… criticizing government’s policies.” Asad Jamal explained that the PPO could “be used to nab all kinds of threats including non-armed political ones too.”

Assumption of Guilt

The next issue that has been raised by attorneys reviewing the PPO is the presumptions of guilt that the PPO encourages. Generally, everyone is innocent of crimes until they are proven guilty, but when it comes to suspected enemy combatants in Pakistan, the opposite is now true. Lawyer and columnist, Yasir Latif Hamdani, says laws like the PPO “shifts the burden of proof on the arrested person, not only of his innocence but of his citizenship. The assumption would be that a person is an enemy alien waging war against Pakistan unless he can prove otherwise. Allowing such a presumption seems counterintuitive to the model of justice in Pakistan, and most of the world, that all individuals are innocent until proven guilty.

Reinventing the Wheel

The question asked by many critics of the PPO is why the law was needed in the first place when there are already a slew of anti-terror laws on the books in Pakistan? Asad Jamal argued that “the preamble to PPO is meant to provide for waging of war against Pakistan, an offence [which is] already provided for in the Pakistan Penal Code.” He goes on to question, “Why do we need a new law in the form of PPO?” Asad Rahim Khan agreed, arguing that it is “better to actually enforce the old laws than invent new ones we won’t enforce either.”

Potential Advantages of PPO

Barrister Amjad Malik, chair of Pakistani Lawyers in the UK, disagrees with the critics, arguing that the PPO was necessary in the absence of specific laws to deal with enemy combatants and terrorists in Pakistan. He explained that some of the PPO provisions deemed draconian by critics exist in current law; for example, security agencies have possessed the right to preventatively detain suspects before the PPO.

Even critics like Asad Rahim Khan have written that the saving grace of the PPO is its mention of creating special jails for suspects and safe-houses to provide greater security for witnesses, judges, lawyers, and court employees. If these aspirations come to life, they could ameliorate the abysmal conviction rates in terrorism cases and allow for the courts to effectively perform their functions without fearing violent retribution by terrorists.

The Role of the Court

In the process of the Senate confirmation, an opposition-led group including PTI has filed for a review of the PPO. However, some in the People’s Party have objected to this, with Senator Farhatullah Babar saying that “it is unwise to take a parliamentary battle to other forums and invite their interference in matters that fall within the domain of parliament alone.”

However, legal experts interviewed generally agreed that the Pakistani judiciary could legitimately get involved in assessing the constitutionality of the PPO. According to Yasir Latif Hamdani, “The courts should get involved…[they] have a duty to test every law on the touchstone of fundamental rights.” If the Pakistani judiciary were to take such a case, Sindhyar Talpur, managing editor of South Asia Jurist, says they could look to the UK Supreme Court for an example. In A and Others v Secretary of State, Talpur says, the House of Lords rejected a law passed by the government to allow indefinite detention of terrorists because it violated the fundamental rights of British citizens.

Balancing Security and Freedoms

The creation of anti-terror legislation like the PPO or Fair Trial Act effect Pakistan’s balance of security and freedom in the age of terrorism. Chief Justice Jillani recently delivered a speech where he stated that all government actors were duty-bound to abide by the rule of law and ensure human dignity, even in the face of terrorism. He explained that the “rule of law was an unending quest.” As such, it is the duty of the ruling administration to “Protect Pakistan” not only from terrorists, but from illegal actions by the state itself, like disappearances, torture or extrajudicial killing.