The ‘Islamisation’ debate in Pakistan should not only be about the implementation of various ‘Islamic laws’ by the state and governments of Pakistan. It should also incorporate the study of the so-called Islamisation of public space, or space that was historically and inherently secular in nature.

One of the most prominent examples in this respect is the manifold growth in the number of mosques and madrassahs in the last 25 years, and this trend’s physical and symbolic extension into the secular spaces of society. For example, ever since the early 1980s, there has been a visible augmentation in the formation of ‘praying areas’ in offices in both private and government institutions, and of the laxities allowed to employees at the workplace regarding prayer timings. However, as can be observed from the findings of various academic and research-based studies (mainly on assorted criminal activity in the country in the last 25 years), the growth in the number of mosques, implementation of Islamic laws, and an increase in regular practice of faith among the populace ever since the 1980s has not helped make society any more law-abiding. In fact, the rate of crime has increased dramatically.

This hasn’t prompted influential sections of the state, media and public at large to evaluate the failure of the ‘Islamisation’ initiatives. On the contrary, the failure of these initiatives to generate a more morally sound society has ironically made its advocates actually accelerate their efforts. For instance, beginning in the 1980s, there are now more religious programmes on television and radio than ever before. Also, more and more drawing-rooms are becoming venues for religious lectures and dars. In fact, even in modern, posh shopping malls, the central sound system is used to broadcast the azaan.

Secular space is rapidly shrinking and the sociology of Pakistan today is strikingly different from what it was some thirty years ago. Advocates of these trends would rightly suggest that social Islamisation could not have taken place without the consent of the majority of the people. True. But one need not be a professional sociologist to determine the resounding failure of this initiative to convert Pakistan into a morally sound community of people.

Social, cultural and economic indicators of the last 25 years suggest a society displaying a religiosity that is convolutedly trying to reach a forced synthesis with modern material wants and ambitions. There is an inherent dichotomy between loud displays of moral piety and the desire to taste the fruits of amoral materialism. Nevertheless, in Pakistan this dichotomy has been turned into a collective attempt to work it as a synthesis.

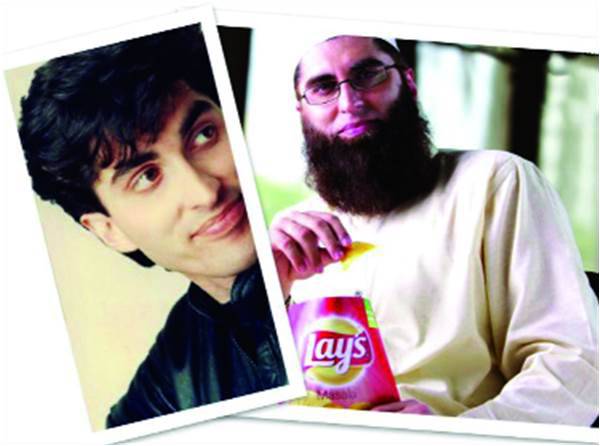

The apologist argument in this respect is that being pious doesn’t mean one can’t be materialistic as well. This apologia can be countered in a number of ways, especially when the piety that is being displayed is supposedly following the dictates of a dyed-in-wool brand of piety in which, for example, music may become ‘haram’, but getting paid to endorse a western brand of chips as ‘halaal,’ is fine.

Addressing such convolutions has become the work of televangelists and ‘modern sounding’ preachers. Their role can be defined as helping mould a workable narrative that is constructed from certain select religious texts and then offered to their audiences as a theological rationale to survive in the modern material world as a practicing Muslim without feeling guilt or angst. This dichotomy is then converted into a religiously rationalised normality.

But the question again arises, how productive has been such an arrangement? It has clearly not turned Pakistan into a better, more law-abiding society than what it was before the so-called Islamisation process kicked in (during the Ziaul Haq dictatorship). As Ziaul Haq’s process failed to address the utopian expectations of the people for the ‘ideal Islamic state’ that he had promised; and as political and economic corruption further eroded Zia’s regime, various fundamentalist groups that had risen in the 1980s, decided to Islamise society from below. The idea was to Islamise all aspects of society so that people would ‘turn from being just Muslims into becoming Islamic.’ Interestingly, the state and the governments even after Zia’s demise allowed this brand of social Islamization to continue, as long as it didn’t exhibit any overt political ambitions. But eventually it did.

The extremists and the fundamentalists were free to carry on Islamising social space, so much so that today it has become impossible to escape religious symbolism and rhetoric in even the most traditionally secular of spaces and surroundings.

The socialising aspects of certain puritanical strains of the faith have been an all-encompassing event. Their symbols and rhetoric abound on billboards, in shopping malls, parks, cars, buses, drawing rooms, on TV screens, in offices and in even in everyday lingo. It seems Pakistanis have lost the capability to separate the religious from the secular.

So what’s wrong with that, some might ask?

Well, for one thing, this trend has consequently moulded a mind-set that has become almost voluntarily vulnerable to the exploitative socio-political manoeuvres of the extremists. This might answer why some sections of the society throw up their arms in disgust after a drone attack but remain awkwardly quiet every time a terrorist slaughters scores of common people, cops and soldiers in a suicide blast.

And perhaps that’s why the Pakistani society may have a ready-made consensus on, say, the dangers of alcohol abuse, but still can’t seem to reconcile to a common consensus on exactly who or what is an extremist.

One of the most prominent examples in this respect is the manifold growth in the number of mosques and madrassahs in the last 25 years, and this trend’s physical and symbolic extension into the secular spaces of society. For example, ever since the early 1980s, there has been a visible augmentation in the formation of ‘praying areas’ in offices in both private and government institutions, and of the laxities allowed to employees at the workplace regarding prayer timings. However, as can be observed from the findings of various academic and research-based studies (mainly on assorted criminal activity in the country in the last 25 years), the growth in the number of mosques, implementation of Islamic laws, and an increase in regular practice of faith among the populace ever since the 1980s has not helped make society any more law-abiding. In fact, the rate of crime has increased dramatically.

This hasn’t prompted influential sections of the state, media and public at large to evaluate the failure of the ‘Islamisation’ initiatives. On the contrary, the failure of these initiatives to generate a more morally sound society has ironically made its advocates actually accelerate their efforts. For instance, beginning in the 1980s, there are now more religious programmes on television and radio than ever before. Also, more and more drawing-rooms are becoming venues for religious lectures and dars. In fact, even in modern, posh shopping malls, the central sound system is used to broadcast the azaan.

Secular space is rapidly shrinking and the sociology of Pakistan today is strikingly different from what it was some thirty years ago. Advocates of these trends would rightly suggest that social Islamisation could not have taken place without the consent of the majority of the people. True. But one need not be a professional sociologist to determine the resounding failure of this initiative to convert Pakistan into a morally sound community of people.

Social, cultural and economic indicators of the last 25 years suggest a society displaying a religiosity that is convolutedly trying to reach a forced synthesis with modern material wants and ambitions. There is an inherent dichotomy between loud displays of moral piety and the desire to taste the fruits of amoral materialism. Nevertheless, in Pakistan this dichotomy has been turned into a collective attempt to work it as a synthesis.

The apologist argument in this respect is that being pious doesn’t mean one can’t be materialistic as well. This apologia can be countered in a number of ways, especially when the piety that is being displayed is supposedly following the dictates of a dyed-in-wool brand of piety in which, for example, music may become ‘haram’, but getting paid to endorse a western brand of chips as ‘halaal,’ is fine.

Addressing such convolutions has become the work of televangelists and ‘modern sounding’ preachers. Their role can be defined as helping mould a workable narrative that is constructed from certain select religious texts and then offered to their audiences as a theological rationale to survive in the modern material world as a practicing Muslim without feeling guilt or angst. This dichotomy is then converted into a religiously rationalised normality.

But the question again arises, how productive has been such an arrangement? It has clearly not turned Pakistan into a better, more law-abiding society than what it was before the so-called Islamisation process kicked in (during the Ziaul Haq dictatorship). As Ziaul Haq’s process failed to address the utopian expectations of the people for the ‘ideal Islamic state’ that he had promised; and as political and economic corruption further eroded Zia’s regime, various fundamentalist groups that had risen in the 1980s, decided to Islamise society from below. The idea was to Islamise all aspects of society so that people would ‘turn from being just Muslims into becoming Islamic.’ Interestingly, the state and the governments even after Zia’s demise allowed this brand of social Islamization to continue, as long as it didn’t exhibit any overt political ambitions. But eventually it did.

The extremists and the fundamentalists were free to carry on Islamising social space, so much so that today it has become impossible to escape religious symbolism and rhetoric in even the most traditionally secular of spaces and surroundings.

The socialising aspects of certain puritanical strains of the faith have been an all-encompassing event. Their symbols and rhetoric abound on billboards, in shopping malls, parks, cars, buses, drawing rooms, on TV screens, in offices and in even in everyday lingo. It seems Pakistanis have lost the capability to separate the religious from the secular.

So what’s wrong with that, some might ask?

Well, for one thing, this trend has consequently moulded a mind-set that has become almost voluntarily vulnerable to the exploitative socio-political manoeuvres of the extremists. This might answer why some sections of the society throw up their arms in disgust after a drone attack but remain awkwardly quiet every time a terrorist slaughters scores of common people, cops and soldiers in a suicide blast.

And perhaps that’s why the Pakistani society may have a ready-made consensus on, say, the dangers of alcohol abuse, but still can’t seem to reconcile to a common consensus on exactly who or what is an extremist.