Cast: Nawazuddin Siddiqui, Anil George, Niharika Singh

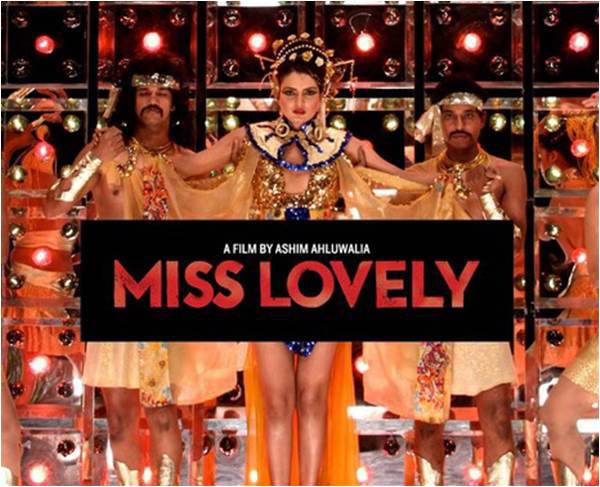

Director: Ashim Ahluwalia

Rating: 3.5 stars

Miss Lovely was made before Nawazuddin Siddiqui was Nawazuddin Siddiqui. Gangs of Wasseypur, Bombay Talkies and Lunchbox were not out when the film premiered at Cannes 2012. When I met Nawazuddin, he told me with a shy smile, “You know, people would just call me for small roles, like if a guy has to get beaten up, or has to shout at someone, or has to die. In Miss Lovely, I’m playing a very soft character. I liked it a lot.”

The remarkable actor that he is, he brings shades of softness to a character we would otherwise dismiss as a sleaze. Based on the horror-porn industry of the 1980s and 1990s, Miss Lovely was originally supposed to be a documentary. The director’s previous documentary, John and Jane, which told the stories of call centre operators in India who assume American names and accents, was a critical success. Ahluwalia intended to make one about the ‘single reels’ of the 1980s.

At the time, midnight shows of regular horror films would be interrupted with this treat for the male patrons – suddenly, between reels, a monster with a molten face would ravage a screaming woman. And then there were the ‘matinees’ – soft porn desi flicks, to which schoolboys and middle-aged men who were afraid of prostitutes and had no way of satisfying their libidos would furtively troop into.

[quote]What if you are aware of the stench of the gutter you are in and want to get out of it?[/quote]

In interviews, Ahuwalia said he witnessed the shooting of a sleaze horror film called Maut ka Chehra in 1998, in the dying days of the C-grade industry. It was being shot in pay-by-the-hour hotels. The cast and crew gossiped about a former colleague who had disappeared. Her body was eventually recovered months later. No one was willing to talk about it. And so, the documentary morphed into a film.

Every now and then, stories come out in the media about the camaraderie in the ‘dirty film’ industry. Miss Lovely looks at the dark side. It’s a dog-eat-dog world, a world with no space for dreams. And yet, the film is shot in muted shades, recreating the 1980s with its colours and texture, following the characters as if we’re walking into a drug-induced hallucination.

What happens when you want more, the film asks. What if you are aware of the stench of this gutter and want to get out of it? What if you aspire to the “real” Bollywood, the money, the glamour, the parties? Can such ambition be anything but futile? In a world like this, where do you find purity? What does it mean to you? What will it do to you if you find that the purity never existed at all?

These are affecting ideas. The film is engaging, especially at the start, when we find ourselves in a film about a haunted house, and then zoom out into the reality of the people behind the projector. Sonu Duggal (Nawazuddin Siddiqui) and his brother Vicky (Anil George) take care of logistics and direction of C-grade films. Vicky wants to cut out the middleman and make money. Sonu has the misfortune of being both a simpleton and an idealist, the perfect raw material for hamartia. On a train from Ajmer to Bombay, he finds his muse (Niharika Singh). It’s love at first sight, and fate seems to reaffirm that this is meant to be. He dreams of a life with his Miss Lovely – he will direct a real film, with that name; she will star in it, and it will be a partnership on and off the screen. But Vicky has uses for Miss Lovely too. And Miss Lovely has uses for them both.

As their story unfolds, the film looks at several important issues – the exploitation of women in the industry, the cynicism, the ambition, the despair, the tussle between trust and betrayal. The film poses the right questions. The story could have been a wonderful vehicle for these, with the cast turning in solid performances. Sadly, though, the film suddenly turns predictable and melodramatic.

There was so much that the film could have done in bringing out the dynamic between the brutally pragmatic Vicky, and the stoically romantic Sonu. One wishes the crucial parts of the film, its turning points, had been as subtle as the lead-up to them. It has some excellent moments, perfectly timed. It has some truly memorable performances. Ashim Ahluwalia’s understanding of the industry comes through, and the film has an authentic feel. But, somewhere, it loses the plot and gets tedious. Unfortunately, the censor’s scissors have also taken away some of the bits which brought home the starkness of the industry, and I wish the version that was screened at Cannes could have had a larger audience.

Director: Ashim Ahluwalia

Rating: 3.5 stars

Miss Lovely was made before Nawazuddin Siddiqui was Nawazuddin Siddiqui. Gangs of Wasseypur, Bombay Talkies and Lunchbox were not out when the film premiered at Cannes 2012. When I met Nawazuddin, he told me with a shy smile, “You know, people would just call me for small roles, like if a guy has to get beaten up, or has to shout at someone, or has to die. In Miss Lovely, I’m playing a very soft character. I liked it a lot.”

The remarkable actor that he is, he brings shades of softness to a character we would otherwise dismiss as a sleaze. Based on the horror-porn industry of the 1980s and 1990s, Miss Lovely was originally supposed to be a documentary. The director’s previous documentary, John and Jane, which told the stories of call centre operators in India who assume American names and accents, was a critical success. Ahluwalia intended to make one about the ‘single reels’ of the 1980s.

At the time, midnight shows of regular horror films would be interrupted with this treat for the male patrons – suddenly, between reels, a monster with a molten face would ravage a screaming woman. And then there were the ‘matinees’ – soft porn desi flicks, to which schoolboys and middle-aged men who were afraid of prostitutes and had no way of satisfying their libidos would furtively troop into.

[quote]What if you are aware of the stench of the gutter you are in and want to get out of it?[/quote]

In interviews, Ahuwalia said he witnessed the shooting of a sleaze horror film called Maut ka Chehra in 1998, in the dying days of the C-grade industry. It was being shot in pay-by-the-hour hotels. The cast and crew gossiped about a former colleague who had disappeared. Her body was eventually recovered months later. No one was willing to talk about it. And so, the documentary morphed into a film.

Every now and then, stories come out in the media about the camaraderie in the ‘dirty film’ industry. Miss Lovely looks at the dark side. It’s a dog-eat-dog world, a world with no space for dreams. And yet, the film is shot in muted shades, recreating the 1980s with its colours and texture, following the characters as if we’re walking into a drug-induced hallucination.

What happens when you want more, the film asks. What if you are aware of the stench of this gutter and want to get out of it? What if you aspire to the “real” Bollywood, the money, the glamour, the parties? Can such ambition be anything but futile? In a world like this, where do you find purity? What does it mean to you? What will it do to you if you find that the purity never existed at all?

These are affecting ideas. The film is engaging, especially at the start, when we find ourselves in a film about a haunted house, and then zoom out into the reality of the people behind the projector. Sonu Duggal (Nawazuddin Siddiqui) and his brother Vicky (Anil George) take care of logistics and direction of C-grade films. Vicky wants to cut out the middleman and make money. Sonu has the misfortune of being both a simpleton and an idealist, the perfect raw material for hamartia. On a train from Ajmer to Bombay, he finds his muse (Niharika Singh). It’s love at first sight, and fate seems to reaffirm that this is meant to be. He dreams of a life with his Miss Lovely – he will direct a real film, with that name; she will star in it, and it will be a partnership on and off the screen. But Vicky has uses for Miss Lovely too. And Miss Lovely has uses for them both.

As their story unfolds, the film looks at several important issues – the exploitation of women in the industry, the cynicism, the ambition, the despair, the tussle between trust and betrayal. The film poses the right questions. The story could have been a wonderful vehicle for these, with the cast turning in solid performances. Sadly, though, the film suddenly turns predictable and melodramatic.

There was so much that the film could have done in bringing out the dynamic between the brutally pragmatic Vicky, and the stoically romantic Sonu. One wishes the crucial parts of the film, its turning points, had been as subtle as the lead-up to them. It has some excellent moments, perfectly timed. It has some truly memorable performances. Ashim Ahluwalia’s understanding of the industry comes through, and the film has an authentic feel. But, somewhere, it loses the plot and gets tedious. Unfortunately, the censor’s scissors have also taken away some of the bits which brought home the starkness of the industry, and I wish the version that was screened at Cannes could have had a larger audience.